Tino Mapatya

Back in High School I was not a big fan of history. The whole Sarajevo incident story and the Treaty of Versailles in the Hall of Mirrors was not the kind of reading a young mind would want to spend hours on.

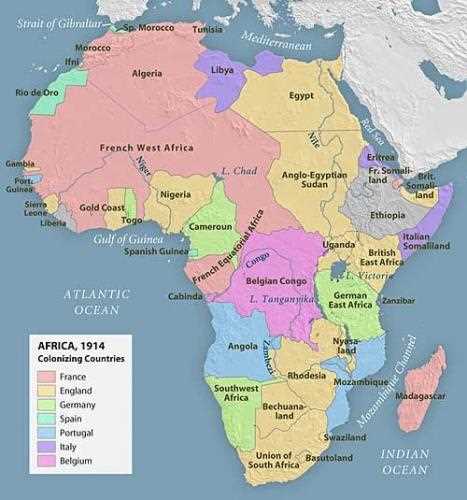

Only later did I learn to see the story behind the topics like “The Partition of Africa” and place them in their position in relation to day to day lives.

Today we will have a history lesson, because history is important.

If we do not look back at our history, we can sometimes fail to see the future correctly.

True, we should not get too stuck on the past, but it helps to know what that past was.

The outpouring of love and emotion in Zimbabwe, over the demise of the Queen of England, Elizabeth the Second showed that colonialism was a thorough job that was done so completely and effectively in this country.

The ascension to the throne of King Charles lll has been met with protests and an increasing call for a look at what the monarchy means for Britain. Countries across the world are making moves to become republics and remove the British monarch as head of state. It is off tune that the king of Britain remains head of state for so many nations.

It is interesting that British citizens seem content to be called subjects at home. Likewise, the acceptance of a perpetual lineage of hereditary privilege and supremacy makes a jarring noise.

History can be brutal. It cannot be undone or rewritten. It can, however, be made right. We will look at the hand of the Royal family on Zimbabwe. We will look at the history of the first two kings called Charles.

In England they wear poppies to commemorate the 1st World War and the all other incidents where armed forces passed away in battle. These events are not defined by time and can stretch back as far as World War 1, or further. It is commendable to respect and honour the departed.

The Holocaust in Germany is commemorated and remembered and no one can belittle it without suffering tremendous backlash. Again, it is very important that atrocities are remembered and should never be allowed to recur.

Slavery and colonialism must be remembered and accorded their correct place in history as told by the people who suffered it, not by those who profited from it.

The British royal family was the driver of Britain’s desire to become Great. The colonialists went across the globe pledging to do great work for “God King, (or Queen) and country.”

The church provided the moral distractions. The Royal family provided the legal authority through Charters and the country provided the military strength to overpower nations that were developing their own civilisations.

In 1836, a British colonialist named Robert Moffat prevailed upon the Ndebele king Mzilikazi to sign a “friendship treaty” that would allow white settlers to move into the country from South Africa.

In 1870 John Swinbourne, having realise the immense natural wealth in the land, convinced King Logengula to sign the Tati Concession, which allowed him and his countrymen to prospect for minerals. Apparently, among the fanciful stories spread by the settlers was that they were looking for medication to help keep their queen in good health.

In 1887, Piet Grobler, a representative of the Boers, who had landed in modern day South Africa and were looking to expand into the rest of Africa came to King Lobengula to negotiate an agreement that would allow the Boers to move into what is now Zimbabwe. The Boers promised to protect the Ndebele against any enemies and to be their good friends.

The agreement was signed.

Stung into action, the British sent Robert Moffat’s son, John Moffat to King Lobengula to advise him that the Boers were tricking him and that he had a better deal that would promote greater secure and cooperation for the king. The second Moffat Treaty was signed.

Related Stories

The British team had now set their sights firmly on the mineral wealth of the plateau between the Zambezi and Limpopo rivers. In 1888 Charles Rudd came through with a detailed document that would become known as the Rudd Concession, when it was signed on 30 October 1888.

The Rudd Concession, in summary, made King Lobengula hand over all the mineral and mineral rights of his land. The most interesting phrase in this document was “I, Lobengula, King of Matabeleland, Mashonaland, and other adjoining territories, in exercise of my sovereign powers, and in the presence and with the consent of my council of indunas, DO HEREBY GRANT AND ASSIGN UNTO THE SAID GRANTEES, THEIR HEIRS, REPRESENTATIVES, AND ASSIGNS, JOINTLY AND SEVERALLY, THE COMPLETE AND EXCLUSIVE CHARGE OVER ALL METALS AND MINERALS SITUATED AND CONTAINED IN MY KINGDOMS, PRINCIPALITIES, AND DOMINIONS, TOGETHER WITH FULL POWER TO DO ALL THINGS THAT THEY MAY DEEM NECESSARY TO WIN AND PROCURE THE SAME, AND TO HOLD, COLLECT, AND ENJOY THE PROFITS AND REVENUES, IF ANY, DERIVABLE FROM THE SAID METALS AND MINERALS, subject to the aforesaid payment; and whereas I have been much molested of late by divers persons seeking and desiring to obtain grants and concessions of land and mining rights in my territories, I do hereby authorise the said grantees, their heirs, representatives and assigns, to take all necessary and lawful steps to exclude from my kingdom, principalities, and dominions all persons seeking land, metals, minerals, or mining rights therein “

With this turn of phrase, Rudd, along with his colleagues Rochfort Maguire and Francis Robert Thompson, got legal permission to take whatever action the invaders felt needed to achieve access to the minerals.

In return they offered: “to pay to me, my heirs and successors, the sum of one hundred pounds sterling, British currency, on the first day of every lunar month; and further, to deliver at my royal kraal one thousand Martini–Henry breech-loading rifles, together with one hundred thousand rounds of suitable ball cartridge, five hundred of the said rifles and fifty thousand of the said cartridges to be ordered from England forthwith and delivered with reasonable dispatch, and the remainder of the said rifles and cartridges to be delivered as soon as the said grantees shall have commenced to work mining machinery within my territory; and further, to deliver on the Zambesi River a steamboat with guns suitable for defensive purposes upon the said river, or in lieu of the said steamboat, should I so elect, to pay to me the sum of five hundred pounds sterling, British currency”

Cecil Rhodes was pleased but not satisfied. He approached Queen Victoria to issue him with a Royal Charter whose mandate literally made Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi the property of the British South Africa Company, which was Rhodes’ platform for colonial expansion and the vehicle he intended to drive his “Cape to Cairo” conquest. Cecil John Rhodes secured the Royal Charter and with it, he was as good as the new owner of Zimbabwe.

King Lobengula had, at this time, realised that the British had no intention of sticking to the agreements he had made with them and tried to get the pacts reversed, even sending emissaries to Queen Victoria. His overtures met no success.

In 1890, Cecil Rhodes rolled into the country with the Pioneer Column, a caravan of wagons guarded by heavily armed soldiers. They established military outposts as each major stopping point. That was the origin of Fort Tuli, Fort Victoria (Masvingo), Fort Charter and finally, Fort Salisbury (Harare) in September 1890.

The locals realised quickly they had been played, and launched warfare. However, with spears, bows and arrows, against rifles and the newly released machine guns, the battles were soon over. After the first war, now known as the First Chimurenga or the Chindunduma battle, the mediums of the spirits Nehanda and Kaguvi were captured and beheaded.

Less than half a century after this, Queen Elizabeth the Second came into power in England.

By that time, the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (Zimbabwe, Zambia and Malawi) had grown into a jewel in the colonial crown. Rhodes was long dead but his name lived on.

The Royal charter was never rescinded. The point of this foray into the past is to show how involved the royal family was in the systematic occupation of nations and the subsequent extraction and movement of mineral wealth.

This week Prince Charles became King Charles III. Given the gory past of the last two Charleses, he may have opted for a new name altogether. His role in Zimbabwe is largely that of flying in to receive the Union Jack at Rufaro Stadium on Independence Day in 1980 as the British flag was ceremionially brought down and replaced with the Zimbabwean one.

The Slate has a detailed breakdown of the role the first Charleses played in Africa.

https://slate.com/news-and-politics/2020/07/british-royal-family-slavery-reparations.html

During the reign of King Charles II, from 1660 to 1685, the Crown and members of the royal family invested heavily in the African slave trade. Seeking to bolster the wealth and power of the restored monarchy and to supplant the Dutch in the Atlantic trading system, Charles granted a charter to the Company of Royal Adventurers Into Africa, a private joint-stock company, less than six months after ascending the throne. The charter gave the Royal Adventurers a 1,000-year monopoly over trade, land, and adjacent islands along the west coast of Africa stretching from what was then known as Cape Blanco (western Sahara) in the north to the Cape of Good Hope in the south. The king lent the company a number of royal ships, including a vessel called the Blackamoor, and reserved for himself the right to two-thirds of the value of any gold mines discovered. Controlling English trade with West Africa—in gold, hides, ivory, redwood, and, ultimately, slaves—offered the prospect of a revenue stream that would enable the Crown to gain financial independence from Parliament.

In 1663, the Royal Adventurers received a new charter explicitly granting the company an exclusive right among English traders to purchase enslaved captives on the West African coast and transport them to the English colonies in the Americas. Sponsored by the king’s inner circle and politicians and courtiers expecting to use the African trade for personal profit, the fledgling company set out to deliver thousands of African captives to the English Caribbean. Upon disembarking, Africans who survived the horrors of the middle passage were sold to English buyers or to foreign traders looking to acquire slaves for transshipment to Spanish America. By March 1664, the company had delivered more than 3,000 enslaved men, women, and children to Barbados and 780 African captives to Jamaica.

By the time King Charles II granted a charter to the reorganised Royal African Company of England in 1672, the demand for slave labor in the Americas had intensified. Ensuring a steady supply of African captives to England’s Caribbean and North American colonies promised not only to generate profits for shareholders and the Crown but also to expand England’s imperial footprint in the Atlantic world.

As English planters in the Atlantic colonies clamored for more enslaved Africans, English enslavers profited and the African slave trade expanded. “The Royal African Company of England,” notes historian William Pettigrew, “SHIPPED MORE ENSLAVED AFRICAN WOMEN, MEN, AND CHILDREN TO THE AMERICAS THAN ANY OTHER SINGLE INSTITUTION DURING THE ENTIRE PERIOD OF THE TRANSATLANTIC SLAVE TRADE.” The company’s seal captures how English enslavers, with Crown encouragement, eagerly harnessed the lives and bodies of Africans to generate commercial wealth and build an overseas empire. The seal shows an elephant bearing a castle, flanked by two enslaved African men. Surrounding the figures is the company’s motto: Regio floret patrocinio commercium, commercioque regnum (“By royal patronage commerce flourishes, by commerce the realm”).

These were the adventures of Charles I and Charles II.

It remains to be seen whether Charles III will finally be the royal family member who speaks about the role the British royal family played in colonialism and the subsequent humanitarian and economic disaster their actions unleashed on Africa, Zimbabwe included. There are growing calls for such discussions to be held, and for the royal family to take responsibility for its actions.

The Roman Catholic Church leader Pope Francis recently went to Canada to apologise for the original inhabitants of the land for the role the Catholic church played during the colonial takeover of that land. The ceremony was appreciated by the locals and there are talks of compensation for the pain and suffering caused.

The ship is firmly in King Charles’ dock. He can sink it or sail it.

Leave Comments