Oscar J Jeke

Zim Now Writer

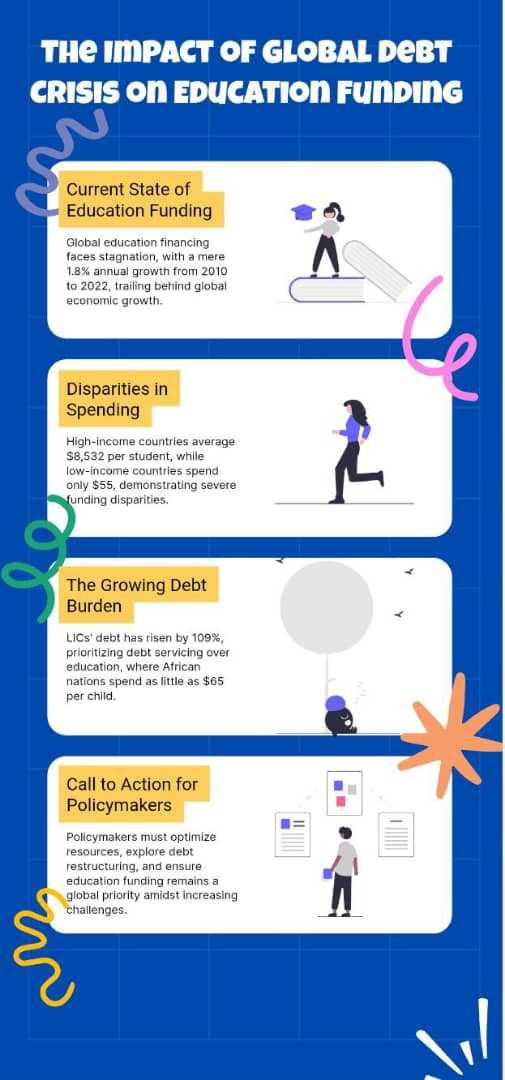

The global education financing landscape has faced significant challenges in recent years, marked by stagnation or decline in public education spending across many nations. This alarming trend unfolds against the backdrop of a growing international debt crisis, particularly in low- and middle-income countries.

The UNESCO Education Finance Watch Report 2024 highlights the interplay between these economic dynamics and their implications for education systems worldwide.

Between 2010 and 2022, global education expenditure increased by just 1.8% annually, lagging behind the 2.8% annual growth of the global economy. However, this modest increase masks stark inequalities. While high-income countries saw education spending rise by only 10% during this period,

LICs and LMICs experienced more substantial growth. Yet, their per capita spending remains grossly inadequate. In 2022, LICs allocated an average of just US$55 per child annually, compared to US$8,532 in HICs.

Over the past decade, LICs and LMICs have seen external debt grow faster than their economies. Debt stocks rose by 109% in LICs and 46% in LMICs, compared to an average gross national income growth of just 33%. By 2022, more than half of LICs were at high risk of debt distress, up from 21% a decade earlier. This debt burden has forced many governments to prioritise debt servicing at the expense of public education.

Related Stories

For example, in 2022, African nations spent an average of US$65 per capita on education—only slightly higher than the US$50 allocated to interest payments on debt. Similarly, South Asian countries spent US$81 on education compared to US$103 on debt servicing.

This decline in global public education expenditure amid escalating international debt represents a dual crisis with far-reaching implications. Among 171 countries analyzed, only 59 met UNESCO's recommended benchmarks for education funding: spending at least 4% of GDP and allocating 15% of total public expenditure to education.

The repercussions of reduced public investment in education are evident in learning outcomes. The financial strains of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated pre-existing educational deficits, leading to a 4–8% decline in math and reading proficiency among 15-year-olds in middle-income countries. Learning poverty—defined as the inability of children to read by age 10—has surged in LICs.

Although international aid for education reached a record US$16.6 billion in 2022, its share of total Official Development Assistance fell from 9.3% in 2019 to 7.6% in 2022, as donors prioritized health and energy sectors. At the same time, households in LICs and LMICs bore a disproportionate share of education costs, often contributing more than 3% of GDP.

Against this backdrop, UNESCO’s report calls for LICs and LMICs to focus on mobilizing domestic resources and improving the efficiency of education spending.

The report states, “Policymakers should address systemic inefficiencies, optimize resource allocation, and explore innovative financing mechanisms like debt swaps or restructuring.”

Robust international cooperation is also crucial to alleviate the dual pressures of debt and educational deficits, ensuring that education remains a global priority.

Leave Comments