Monica Cheru-Managing Editor

The latest U.S. sanctions against militia-linked mineral networks in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) are not just a reaction to human rights abuses — they fit into a decades-long pattern in which Washington’s foreign policy in Central Africa has been shaped by the twin imperatives of securing critical resources and projecting global moral authority.

A Strategic Resource Lens

The DRC’s eastern provinces hold vast reserves of tin, tungsten, tantalum, gold, and increasingly strategic cobalt — minerals essential to global electronics, green technologies, and defense systems. For decades, U.S. resource policy has framed access to these minerals not just as an economic matter, but as a national security priority.

- Cold War era: U.S. policymakers sought Congolese uranium for nuclear weapons programs and industrial minerals to keep Western industry competitive.

- Post–Cold War and “War on Terror” era: “Conflict minerals” provisions in U.S. laws like the 2010 Dodd–Frank Act (Section 1502) sought to clean up supply chains, but also to ensure predictable access for Western manufacturers in a rising China era.

- Today: In an age of strategic competition with Beijing, cobalt and rare earth–linked supply chains are central to U.S. economic and defense planning, making instability in eastern Congo not just a humanitarian concern but a supply-chain threat.

The August 12 sanctions — freezing assets of PARECO-FF, a Congolese mining cooperative, and Hong Kong–based intermediaries — align with this resource-security logic. By targeting militia–trader networks, Washington is signaling that conflict-linked supply chains will be policed with both economic and geopolitical intent.

Human Rights as Policy Currency

The sanctions announcement foregrounds abuses: forced labor, sexual violence, killings, and displacement. This human rights framing is consistent with the State and Treasury Departments’ pattern of using humanitarian narratives to legitimize interventions in resource-rich zones. Historically, such narratives have served dual purposes:

- Building domestic and international political support for sanctions and trade restrictions.

- Creating leverage over governments or armed actors whose control of resources is seen as threatening to Western strategic interests.

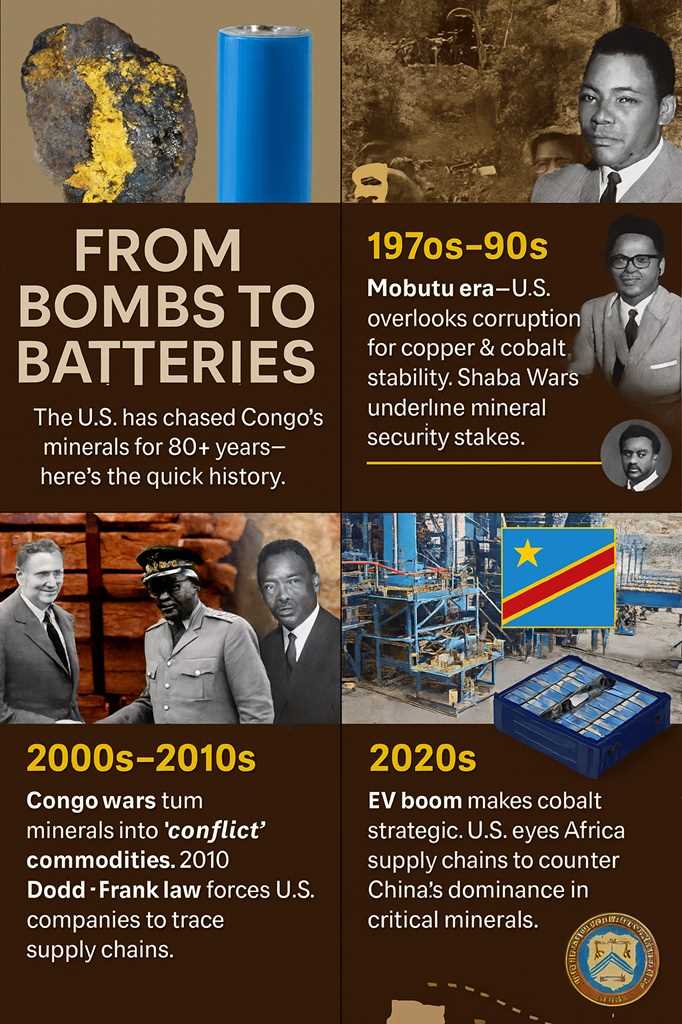

A History of U.S. Engagement in Congo

The U.S. has a deep and controversial history in the DRC:

- 1960s: Backing the removal (and eventual assassination) of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba, partly over fears of Soviet influence and to secure Western access to resources.

- Mobutu era (1965–1997): Support for Mobutu Sese Seko despite corruption and repression, in exchange for a stable pro-Western regime granting access to minerals.

- Post-Mobutu: U.S. policy has oscillated between backing UN peacekeeping, pushing for democratic reforms, and discreetly securing mineral supply routes through allies in Rwanda and Uganda. Critics note that this has often stabilized access to resources for Western firms while leaving Congolese communities in cycles of violence and poverty.

Present Dynamics: Resource Security in a Multipolar Era

The August sanctions come at a time when:

- The M23 rebellion, backed by Rwanda, threatens to reconfigure control over mineral-rich territories.

- China has dramatically increased its investment and infrastructure presence in the DRC, especially in cobalt and copper.

- U.S. “friend-shoring” and critical minerals policies aim to counter China’s dominance in battery and semiconductor inputs.

By striking Hong Kong–based companies linked to PARECO-FF’s minerals, OFAC is both disrupting militia revenue streams and sending a signal to Chinese intermediaries that conflict-linked minerals are a red line in U.S. trade policy.

The Policy Pattern

From uranium for the Manhattan Project to cobalt for EV batteries, U.S. engagement in the Congo has rarely been resource-neutral. The August 12 sanctions reinforce a pattern:

- Identify instability threatening strategic minerals.

- Frame it in human rights terms for diplomatic legitimacy.

- Use sanctions and economic tools to police supply chains.

- Shape the market environment to favor U.S. and allied access.

In short, while Washington’s public line is about saving lives and stopping abuses, the deeper current is about securing the minerals that power America’s technological and military edge — a continuity that stretches from Lumumba’s time to the cobalt wars of today.

Related Stories

U.S.–Congo Minerals & Policy: A Timeline (1940s–2025)

1942–45 — Shinkolobwe & the Bomb

Uranium from Shinkolobwe mine (Katanga) supplies the Manhattan Project—cementing Congo’s minerals as a U.S. strategic interest.

1960 — Independence, Crisis, Cold War

Congo gains independence; copper/cobalt-rich Katanga secedes. The U.S. views the country through an anti-Soviet, resource-security lens.

Jan 1961 — Lumumba Assassinated

Patrice Lumumba is killed amid superpower intrigue. U.S. policy tilts toward any “stable” arrangement that preserves Western access to minerals.

1965–97 — Mobutu Era

U.S. backs Mobutu Sese Seko despite kleptocracy, prioritizing Cold War alignment and steady flows of copper, cobalt, and industrial minerals.

1977–78 — Shaba (Katanga) Wars

Fighting in mineral heartlands prompts Western (incl. U.S.) support for Mobutu—stability framed as essential for global supply.

1996–2003 — Congo Wars I & II

Regionalized wars over territory and resources (coltan, gold, tin). U.S. backs peacekeeping/diplomacy while manufacturers quietly diversify supply chains.

2010 — Dodd–Frank §1502

U.S. law targets “conflict minerals” (3TG: tin, tungsten, tantalum + gold). Human-rights language meets a push for cleaner, predictable supply chains.

2013–16 — Compliance Era

SEC rules, audits, and corporate reporting begin reshaping electronics sourcing; Congo’s artisanal sector is partially squeezed toward traceability.

2018–22 — Cobalt Supercycle & China’s Rise

Global EV boom spotlights DRC cobalt; Chinese firms expand stakes in copper–cobalt belts. U.S. shifts to “critical minerals” strategy and friend-shoring.

Dec 2022 — DRC–Zambia EV Supply MOU (U.S.-Africa Summit)

Washington backs a regional battery value-chain vision—signaling interest in moving from raw ores to midstream processing in Africa.

2023–24 — Sanctions & Designations

U.S. uses Magnitsky/OFAC tools against actors tied to conflict mining and abuses—merging rights rhetoric with supply-chain policing.

Aug 12, 2025 — New OFAC Sanctions

U.S. designates PARECO-FF, a Congolese cooperative, and two Hong Kong firms alleged to funnel conflict minerals to global markets—explicitly linking human-rights abuses to protection of “critical minerals vital for national defense.”

Leave Comments