Patience Muchemwa

Senior Reporter

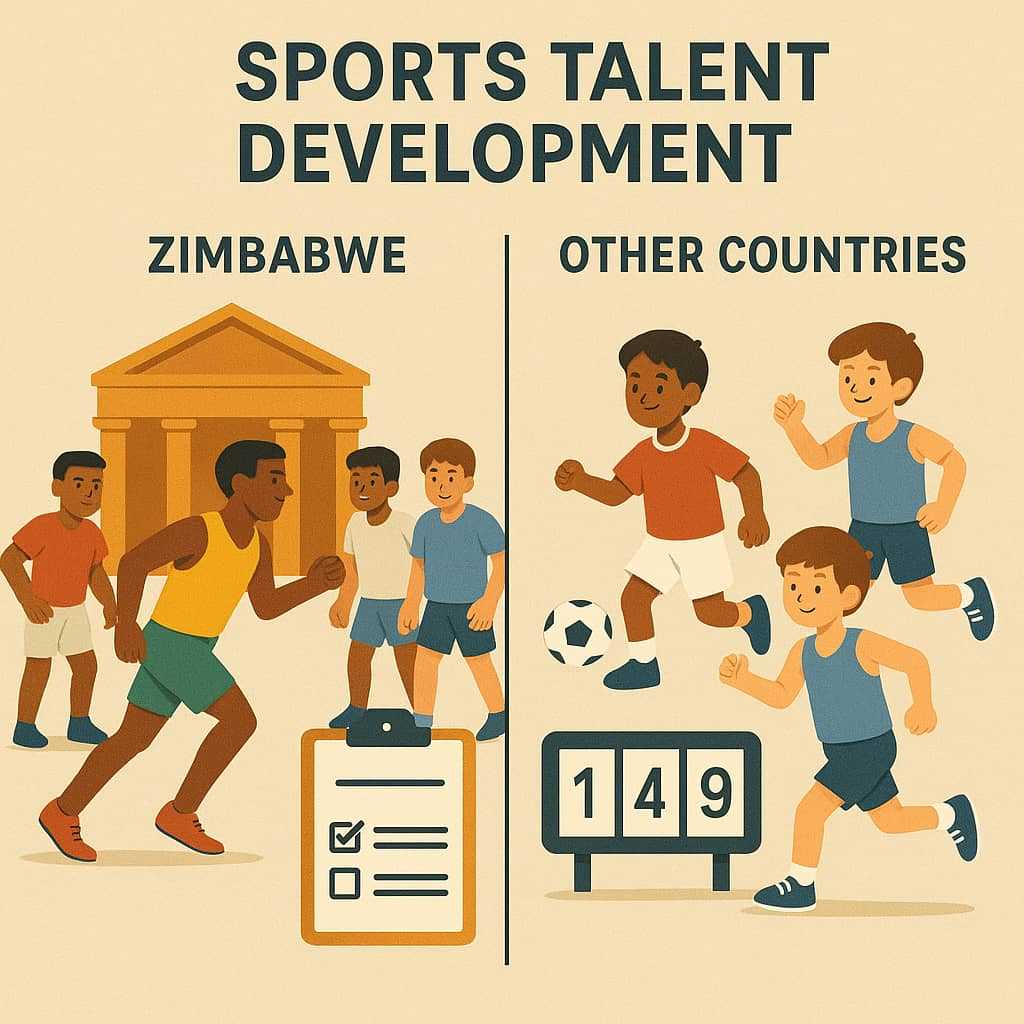

In many parts of the world, sporting talent is nurtured from an early age, with structured development programs and competitive youth leagues serving as stepping stones toward professional careers. However, in Zimbabwe, the story is markedly different. Most athletes only discover their talents in high school or even later—missing out on crucial early development that could place them on the global sporting map.

Gerren Muwishi, the captain of Zimbabwe’s national athletics team, is a prime example. Despite his current success on the track, Muwishi only realized his sprinting potential during his second year at the University of Zimbabwe. By that time, many international athletes his age were already competing in high-profile international events, having come through rigorous youth programs and age-group competitions.

“In Zimbabwe, talent is stumbled upon—not groomed,” Muwishi once remarked in an interview. His story is far from unique.

Related Stories

Unlike countries such as the United States, the United Kingdom, or South Africa—where national youth leagues and academies are the norm—Zimbabwe lacks a consistent framework to identify and nurture sports talent at an early age. In the U.S., for instance, children can begin competing in organized leagues as young as five, progressing through high school, college, and national junior teams, often under the guidance of trained scouts and professional coaches. These systems not only hone skills early but also provide exposure and scholarship opportunities.

In Zimbabwe, the situation is often reactive rather than proactive. When international youth tournaments arise, such as the International Handball Federation (IHF) Trophy Zone VI competitions for under-18 and under-20 players, national teams are hastily assembled through open trials. These trials, though necessary, are frequently marred by allegations of favoritism and lack of transparency. “Sometimes it’s not the best talent that gets selected,” one young athlete commented anonymously. “It’s about who you know.”

The same concerns extend to football and several other sports codes. The absence of permanent national youth teams means there's no continuous development or tactical training. This disrupts long-term planning and makes it difficult for teams to gel before major competitions.

Another deeply troubling trend is the rise of age cheating. With no consistent tracking of athlete development from a young age, it becomes easier for players to manipulate their ages—claiming to be younger than they are to qualify for junior competitions. While this is a global issue to some extent, countries with structured youth systems and reliable databases have largely minimized such practices. In contrast, Zimbabwe’s fragmented system makes detection nearly impossible.

In response to these challenges, the Zimbabwe Football Association (ZIFA) has initiated efforts to tap into the diaspora, particularly targeting UK-based players who have benefited from structured youth development systems. The ZIFA Normalisation Committee has included several uncapped British-born players in the squad for upcoming 2026 World Cup qualifiers. Players such as Andy Rinomhota (Cardiff City), Tivonge Rushesha (Reading), Marley Tavaziva (Brentford), Isaac Mabaya (Liverpool), and Leon Chiwome (Wolverhampton Wanderers) have been given the opportunity to represent Zimbabwe. ZIFA President Nqobile Magwizi and national team coach Michael Nees have been actively scouting and encouraging UK-based talents under the age of 20 to apply for national representation—acknowledging the value of players raised in systems that prioritize early development.

This strategy of reaching abroad isn’t limited to football. Tendai Tagara, President of the National Athletics Association of Zimbabwe (NAAZ), has also voiced strong belief in athletes based outside the country. According to Tagara, Zimbabwean athletes abroad benefit from consistent exposure to competitive races, superior training environments, and state-of-the-art facilities. Back home, the local athletics scene is limited by a lack of domestic competition, forcing athletes to rely on a few events in neighboring countries. Zimbabwe also lacks electronic timing systems—an essential tool for accurate performance tracking and qualification—making it even harder for local athletes to meet international standards.

Countries like Germany and South Africa have dedicated youth academies and national junior leagues that offer young athletes year-round competition and continuous development. Zimbabwe, despite its abundance of raw talent, continues to miss opportunities due to underinvestment in grassroots sports infrastructure and planning.

Leave Comments