Oscar J Jeke

Zim Now Reporter

For more than two decades, Zimbabwe has wrestled with the fallout of its land reform program, one of the most consequential and controversial policies in post-independence Africa.

Originally framed as a corrective measure to colonial-era land injustices, the reforms initiated by the government of Robert Mugabe in the early 2000s spiraled into economic disaster, social fragmentation, and international isolation.

Today, the government of President Emmerson Mnangagwa is attempting a dramatic course correction: initiating compensation payments to former commercial farmers, both local and foreign, who were dispossessed during the reform era. But is this truly a new chapter, or just a rebranding of old tactics?

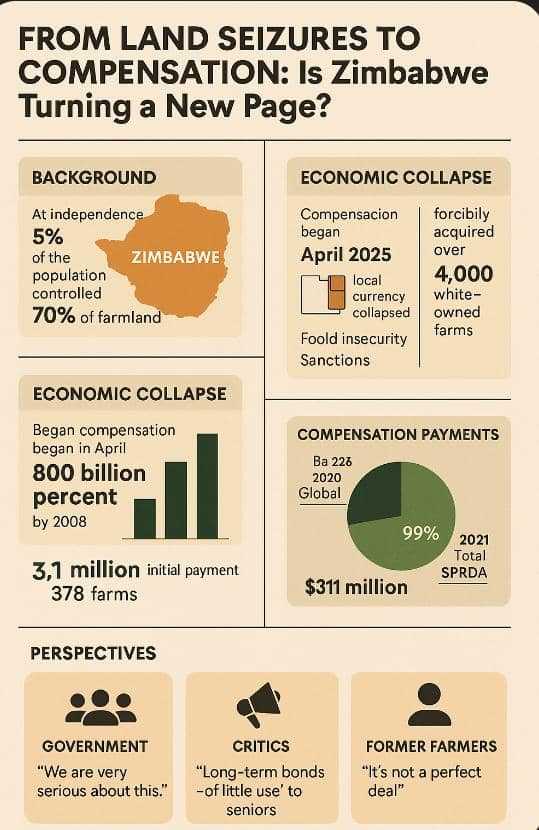

At independence in 1980, approximately 5% of Zimbabwe’s population predominantly white controlled nearly 70% of the country’s most fertile farmland. Mugabe’s response came in the form of a fast-track land reform program launched in 2000, which aimed to redress this imbalance by forcibly acquiring over 4,000 white-owned commercial farms.

While the initiative was applauded by many Zimbabweans for addressing historical inequalities, the implementation was chaotic and frequently violent.

As a result, agricultural production which had accounted for 40% of Zimbabwe’s exports collapsed. According to a 2010 investigation by ZimOnline, Mugabe and his inner circle appropriated nearly 40% of the 14 million hectares seized.

The economic cost was catastrophic. Hyperinflation soared to 500 billion percent by 2008, the local currency collapsed, and food insecurity became widespread. Zimbabwe’s international standing deteriorated rapidly, leading to sanctions and the suspension of support from institutions like the World Bank and IMF, from which Zimbabwe has been in arrears since 2000 and 2001 respectively.

Now, in a gesture that is both symbolic and strategic, Mnangagwa’s administration has begun paying compensation to some of the farmers affected.

In April 2025, Finance Minister Mthuli Ncube announced an initial payment of US$3.1 million to 378 farms a mere 1% of the total US$311 million compensation approved for 740 farms under the 2020 Global Compensation Deed. The remainder will be issued in U.S. dollar-denominated Treasury bonds with maturities ranging from 2 to 10 years and a 2% annual coupon rate.

"The payments will continue. We are very serious about this," Ncube said. According to the Ministry of Finance, these bonds are tax-exempt, liquid assets, and prescribed assets, meaning they can be traded, inherited, and used as collateral.

Designed to attract institutional investors like pension funds, the bonds also include measures to ease initial placement and ensure long-term participation.

Related Stories

However, not all stakeholders are convinced. Critics have called the payment a publicity stunt, arguing that long-term bonds are of little use to elderly former farmers.

“They are going to their graves without receiving any compensation,” said one union official. Economist Tony Hawkins was blunt in his assessment: “We continue to accumulate arrears because we are unable to service our foreign debt, so we can’t really afford to take on new debt commitments… It’s derisory, the more you look at it.”

Andrew Pascoe, former head of the Commercial Farmers’ Union and signatory to the 2020 agreement, expressed a more optimistic view: “We are extremely grateful,” he said. But even among former farmers, the consensus is cautious. "Look, it's not a perfect deal. But there was no other alternative," said Harry Orphanides, one of the union's negotiators.

Meanwhile, compensation is also being extended to foreign farmers protected by Bilateral Investment Promotion and Protection Agreements, including those from Belgium and Germany. In 2024, the government allocated US$20 million to begin payments on these claims, with disbursements already underway for a total liability of US$145.9 million across 56 cases.

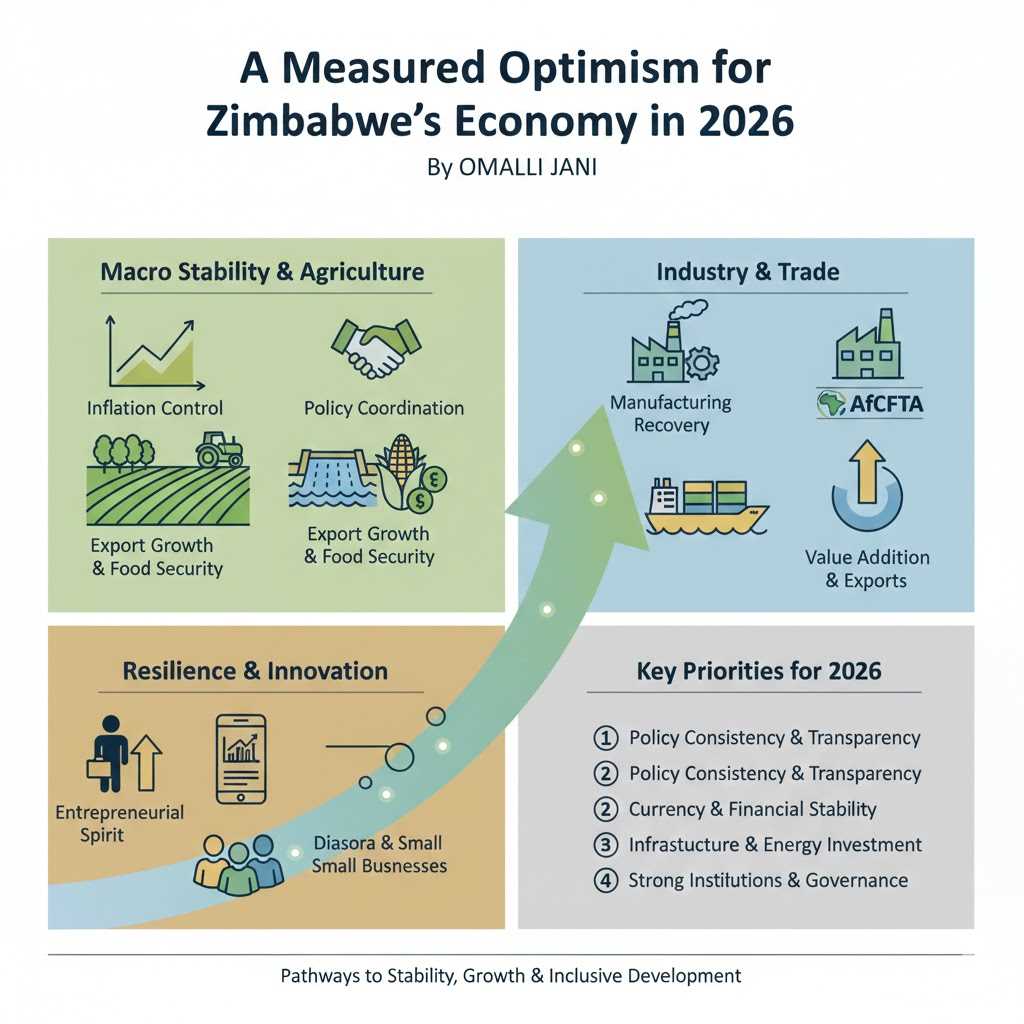

The government’s motivation is not purely altruistic. Zimbabwe is trying to resolve its US$21 billion public debt and unlock access to international credit. The African Development Bank, which is facilitating arrears clearance discussions, has emphasized that the land compensation process is “central” to Zimbabwe’s re-engagement strategy. AfDB President Akinwumi Adesina noted the country had "made a lot of progress, against all odds," and urged acceleration of compensation payments.

Beyond compensation, Mnangagwa has launched a new land policy allowing resettled Black farmers to obtain transferable title deeds. Under Mugabe, beneficiaries were given 99-year leases that were not bankable, limiting their ability to secure financing. The new policy marks a seismic shift. "This marks a major shift," the Associated Press reported, explaining that these titles allow land to be used as collateral and sold between "indigenous Zimbabweans."

But even here, skepticism persists. Professor Ian Scoones of the University of Sussex cautioned that, "there is still confusion over tenure rights" and argued for improved land administration before such reforms can succeed. Other critics note that barring non-indigenous Zimbabweans from buying land perpetuates racial exclusions and inhibits true market development.

The question of justice also looms large. Many resettled farmers have built their lives around these lands. What happens if former owners wish to reclaim them? Will new occupants be displaced? The government insists the program is about compensation, not land restitution, but tensions remain.

A group of liberation war veterans has taken the government to court, challenging the legality of the GCD. Led by former Finance Minister Tendai Biti, the group argues the agreement was not approved by Parliament and undermines the principles of the land reform. They contest the valuation methodology and claim the deal violates the constitutional definition of land ownership and improvements.

Despite the controversies, this compensation program represents a historic milestone. For the first time, a Zimbabwean government is publicly acknowledging the need to address the consequences of its land policy. Whether driven by political necessity, economic strategy, or a genuine commitment to justice, the policy marks a potential turning point.

Still, questions linger about the sustainability and fairness of the process. With US$3.5 billion ultimately owed and only US$1 billion raised domestically so far, much hinges on Zimbabwe’s ability to secure international loans. Given the country’s limited cash reserves and reliance on foreign currency inflows from remittances, tobacco, gold, and horticulture exports, the risk of overburdening future budgets is real.

The compensation program may help Zimbabwe restore its international reputation, attract investment, and reinvigorate its agricultural sector. But it must be accompanied by transparency, institutional reforms, and equitable land access policies.

Zimbabwe is indeed turning a page but whether it is a fresh chapter or a recycled script will depend on what comes next. Without genuine implementation and inclusive governance, the promise of compensation may remain just that: a promise.

Leave Comments