- All candidates registered for ZIMSEC examinations must be granted access.

- Dress codes and grooming policies cannot be weaponized to deny exams.

- Disciplinary cases must be handled after the examination window.

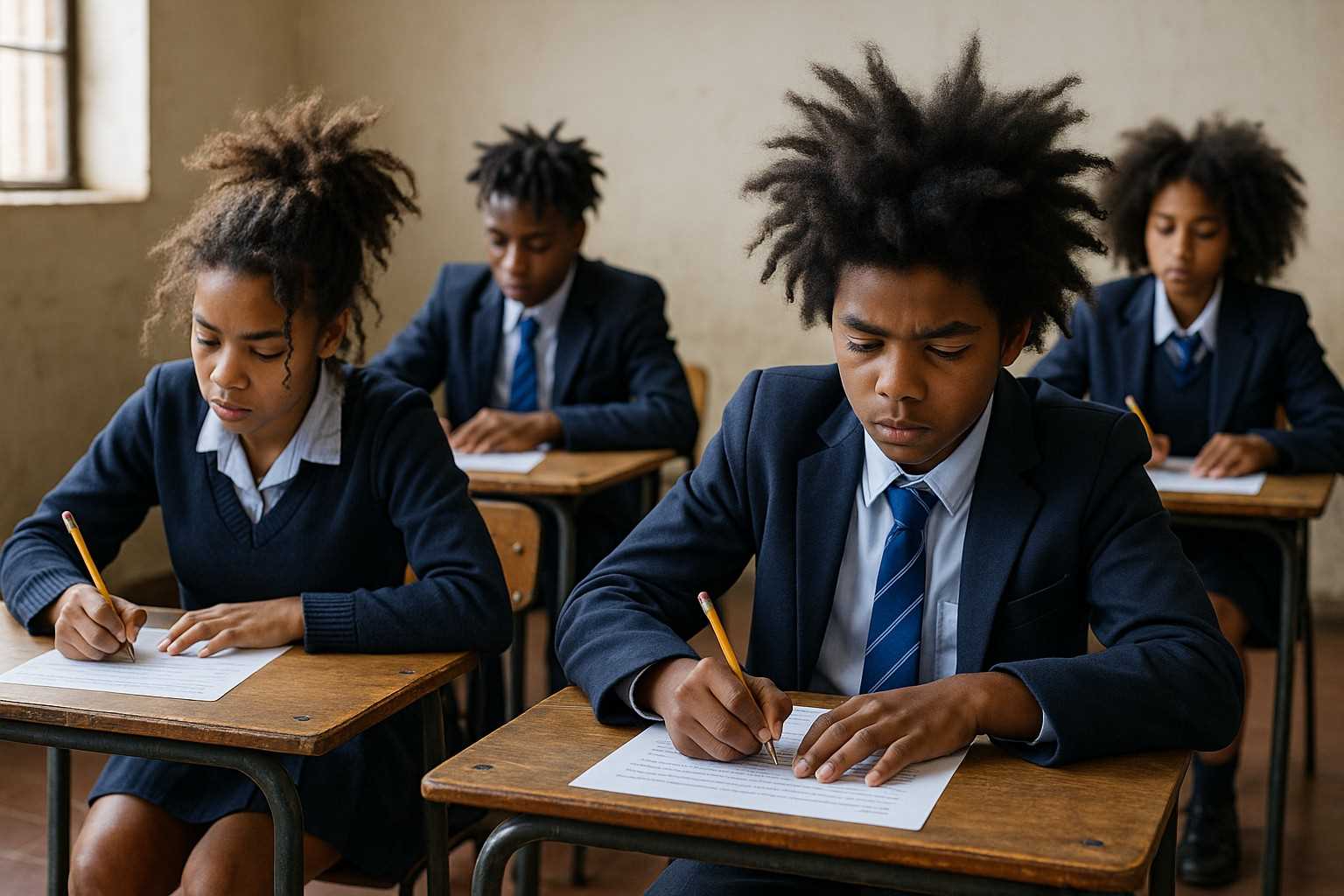

The school head and director arrested for barring nine learners from sitting for their ZIMSEC examinations over what they classified as “inappropriate hairstyles” could face up to 10 years in prison if convicted of criminal abuse of office—one of Zimbabwe’s most serious public-duty offenses under Section 174 of the Criminal Law Code.

Primary and Secondary Education Minister Torerai Moyo announced that the pair, now assisting police with investigations, were arrested following a Ministry of Primary and Secondary Education inquiry that found their actions to be an unlawful and discriminatory obstruction of the learners’ constitutional right to education.

He condemned the conduct as a direct breach not only of ministry policy but also of national law. Moyo, writing on X, said he was “deeply concerned” by the incident, reiterating that public examinations are sacrosanct and that no disciplinary issue—unless life-threatening—can be used to block a registered learner from sitting a national exam.

He stated that the Ministry has long-standing, binding guidelines that explicitly stop authority figures from using disciplinary issues to bar learners from exam sitting.

He described the exclusion of the nine children as “unjust, unlawful, and a violation of policy and constitutional principles. He said the ministry has already issued a directive to all schools reinforcing these rules and is engaging school heads nationwide to ensure similar breaches do not recur.

Legal experts say prosecutors have at least three strong pathways to bring the head and director to account.

They said the duo can be charged for criminal abuse of office (Section 174(1)), which carries a penalty of up to 10 years in jail. This statute criminalizes any act by a public officer that is inconsistent with their duties and prejudices another person.

“A school head and a director, entrusted with administering a public education service, fall squarely under this definition, as by blocking learners from a national exam, they acted contrary to the Education Act, violated ministry directives, and caused demonstrable prejudice,” a Harare lawyer said.

He said this is the most likely and most serious charge.

Related Stories

He said they could also face discriminatory conduct under the Education Act, which prohibits discrimination on any arbitrary ground. Hairstyle-based exclusion is considered arbitrary and illegal when it impedes access to education. This carries fines and administrative sanctions and strengthens the main charge.

The third charge could arise from violation of constitutional rights. The lawyer said Section 75 guarantees the right to basic education. He further explained that while this is not likely to come as a standalone criminal charge, intentional violation of this right weighs heavily in sentencing.

He said it also opens the door for civil litigation by affected families, unless the government moves in immediately to ensure that the affected learners sit their exams and their results come out at the same time as their peers.

Moyo said the ministry is exploring avenues with ZIMSEC to allow the affected learners to write their missed papers. The priority, he said, is ensuring the students do not suffer long-term academic harm because of an unlawful act by adults in authority.

The lawyer said the courts can impose a fine or both, and the ministry can decide on suspension, demotion, or dismissal.

Zimbabwe has had sporadic cases in which learners were barred from class or school activities over hairstyles, uniforms, or grooming issues—but rarely has punitive action reached this level.

Moyo urged all schools to prioritize the welfare of learners and to seek guidance rather than impose punitive measures that jeopardize children’s futures.

“Education is a fundamental right,” Moyo said. “It is our collective duty to safeguard it.”

Leave Comments