Bhola is coming off what staff describe as one of its strongest festive trading periods yet.

“We closed doors at 7pm on Christmas Day, but it took about two hours to clear out the shoppers who were still inside,” said a staff member. On Boxing Day, the store remained busy, with steady queues made up mostly of families with loaded trolleys.

There are no official retail statistics to confirm the scale of festive performance as Zimbabwe does not publish granular, real-time retail data.

But on-the-ground indicators appearances this festive season tell a consistent story: Bhola did very well.

That picture stands in sharp contrast to the situation unfolding at OK Zimbabwe. Just days after the festive rush, OK confirmed the closure of its Bon Marché outlet at Sam Levy’s Village.

The group has repeatedly cited regulatory pressure, competition from tuck shops, and an increasingly hostile operating environment as reasons for its struggles, even releasing some press statements to blame government for its failure.

OK executives have been vocal in arguing that excessive regulation and the growth of informal retail have hollowed out the formal sector. The tuck shop has been positioned as an existential threat.

Yet Bhola is expanding into spaces where OK has retreated. Bhola Long Cheng is thriving in the same vicinity that OK Marimba failed. In Marondera, Bhola is operating in a market where OK’s Bon Marché previously failed. OK Kwame Nkrumah is now practically a morgue while Bhola on Nelson Mandela is seeing brisk business.

The same economy. The same regulations. The same consumer base. The same spaces. That alone weakens the argument that formal retail is no longer viable.

Policies do matter, but…

OK’s framing has been publicly challenged before. Treasury Permanent Secretary George Guvamatanga was attacked when he pointed out that South African supermarkets have not collapsed because of spaza shops.

But the emergence of Bhola into the space that OK is calling too tough shows that when formal retail adapts, coexists, and competes. It does not fold and blame the pavement economy.

Related Stories

And it is not just Bhola. At Fife Avenue Shopping Centre in Harare, the contrast is striking. OK’s branch is increasingly quiet, with large sections of underutilised floor space. A few doors away, SPAR Athienitis continues to trade steadily. SPAR is not immune to economic pressure. It is simply adjusting better.

Pick n Pay, too, has closed some outlets and is clearly under strain, but it remains operational. The formal retail sector is under pressure, yes. It is not extinct as OK would have the national psyche believing as it closes doors. It is becoming clearer that the brand is succumbing to terrible management exacerbated by disruptions to the traditional business model.

Bhola’s approach is straightforward. It built its base in hardware, diversified gradually into groceries, competes on price, and offers variety. It sources aggressively locally and in foreign markets and so caters for all comers. It accepts multiple currencies, while placing sensible limits on ZiG transactions to curb arbitrage. It competes with tuck shops on pricing and beats them on trust, product authenticity and range.

OK’s shelves tell a different story. At its Fife Avenue branch, imported brands dominate entire categories such as jam and peanut butter, with more than ten foreign options against one or two local brands. In a forex-constrained economy, that strategic decision to prioritize importing sweets to paying local manufacturers of ready to drink beverages and water is puzzling.

It explains OK’s strained relationships with local suppliers, a long-running issue that has repeatedly surfaced in industry discussions. And raises questions of exactly who is benefitting from the external supply chains.

Selling Assets Instead of Fixing the Business

Under pressure, OK is now looking to sell property. The explanation is that this will unlock liquidity to recapitalise operations. That decision raises serious historical questions. Were the original property acquisitions sound? Do the prices paid and the business rationale stand up to rigorous scrutiny today?

But what’s done is done and is only useful for case studies. What is more crucial is that the OK leadership must explain why it is choosing to dispose of assets in a difficult market instead of extracting value from them. There are models OK could study locally.

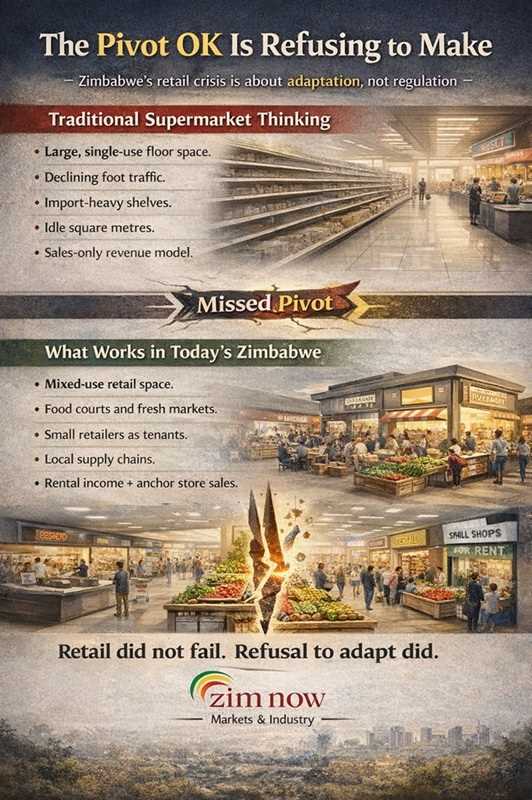

One is Mahomed Mussa. Rather than lamenting informality, Mahomed Mussa has turned small operators into tenants. SMEs are brought inside. Foot traffic is formalised. Rental income is stabilised. Space works harder. And the supermarket benefits from the increased traffic. If OK were to do this with the First Street and Patrice Lumumba (Third) branches, they would be picking the dollar value from the crowds passing their doors every minute.

Another lesson in pivoting that OK can look to is Econet Wireless Zimbabwe which has separated infrastructure from operations through its InfraCo strategy, allowing assets to be managed and sweated differently from the core business.

Many OK sites could be reimagined. OK Chivhu, for example, could function as a major road trip and local shopping centre rather than a traditional supermarket shell. Food courts, fresh produce markets, small retailers, and service outlets would draw crowds. OK can operate a leaner supermarket, riding on tenant-driven traffic.

If Bhola can rise in the same environment where OK is shrinking, while SPAR and Pick n’ Pay are surviving, then regulation is not the decisive factor. Until OK’s board and executive team stop blaming external forces and start interrogating their own decisions, the gap between Bhola’s packed trolleys and OK’s empty aisles will only widen.

Leave Comments