Malilangwe a 50,000-hectare private nature sanctuary in south-eastern Zimbabwe, has a startling new problem – it could soon have too many rhinos.

Like a modern-day Noah's Ark, it is now repopulating other corners of Zimbabwe, returning rhinos to natural habitat where they haven't set foot for decades.

Rhinos were poached to near extinction in Zimbabwe. Now a private wildlife sanctuary is reintroducing them to places where they once roamed free.

On the black market, rhino horn can sell for more than its weight in gold. While it has no proven medical benefits, some believe its powdered form has near mythical powers of healing, curing ailments from hangovers to cancer.

Soaring demand has fuelled a thriving business for ruthless poaching syndicates across southern Africa. After trophy hunting in the 19th century and rampant poaching in recent decades, one of Africa's most iconic animals – the black rhino – has been driven to near extinction. Cruel economics make them more valuable dead and dehorned than alive.

In Malilangwe, GPS trackers, roughly the size of a box of matches, at the horn's base are being inserted in rhino horns to save them.

The process looks brutal but if done above the growth plate is as painless for the rhino as clipping your fingernails. When the job is complete it will better enable the scientists at the Trust, to track the animals’ every move.

It's conservation techniques like this that have helped Malilangwe become one of Africa's most successful rhino sanctuaries.

Over the past two-and-a-half decades, it's played an outsized role in bringing the black rhino, one of the world's most endangered animals, back from the brink. It's also had remarkable success boosting white rhino numbers.

Starting with a few dozen rhinos in 1996, the park's black rhino herd has increased by more than 600 per cent and its white rhinos by 900 per cent, even as waves of poaching across Africa decimated rhino populations elsewhere. Over 400 rhinos now roam the park.

Sarah Clegg, an ecologist who has been studying black rhinos for 25 years, says the data these GPS units beam back will have "huge implications for helping us understand how rhino use the landscape throughout the day." It will show how far they roam and where they cluster in the park.

It's invaluable information as Malilangwe now looks to find suitable homes for its rhinos in other parts of Zimbabwe where they have been virtually wiped out. "That helps us to choose areas that are going to meet their needs," she says.

Across Africa, there's a dire need to rebuild rhino populations after decades of habitat loss and poaching. At the turn of the 20th century, it's estimated half-a-million rhinos roamed Africa and Asia.

Today that number stands at just 27,000, with most behind protective fences in private reserves, or in a select number of national parks with the resources to resist poachers. Few now can survive in the wild, where they are easy prey.

Africa's poaching problem has come in a series of waves over the past four decades, with the most recent crisis kicking off in 2008. In South Africa, home to the world's largest rhino population, just 13 rhinos were killed by poachers in 2007.

In the seven years that followed, the annual toll rose a staggering 9,246 per cent, peaking in 2014 when 1,215 rhinos were killed. Conservationists' hopes that the poaching problem had been brought under control were shattered.

Across the African continent, 11,000 rhinos have been killed by poachers since 2008. While poaching has gradually declined in more recent years, it's never returned to the low levels seen in the early 2000s. Last year, poachers killed more than a rhino a day.

When the not-for-profit Malilangwe conservancy was founded in 1994, Zimbabwe's white and black rhinos had already been decimated. Black rhinos in particular had been hard hit by poachers.

By 1998, the conservancy had imported 28 black and 28 white rhinos from South Africa and set out on a what might have seemed a quixotic bid to turn a vast tract of land degraded by cattle ranching into a sanctuary where native wildlife could flourish.

Related Stories

The conservancy began an intensive monitoring and protection program, mostly funded by private donors as well as tourism ventures in the reserve. "Protecting rhinos is difficult, it costs a lot of money," says Malilangwe's executive director Mark Saunders. "It takes experience. It takes a lot of time, it takes a lot of patience and energy."

Malilangwe Trust also runs the ultra exclusive Singita Pamushana Lodge and other tourist facilities.

Last year 10 of Malilangwe's black rhinos were translocated to neighbouring Gonarezhou National Park. In the early 1980s, Gonarezhou was ground zero for poachers. The jewel in Zimbabwe's wildlife crown had its rhinos completely wiped out.

In May 2021, the big move began. Malilangwe was one of three private parks who together translocated 29 rhinos to Gonarezhou. At 5,000 square kilometres, Gonarezhou is 10 times as big as Malilangwe and has the infrastructure and resources to handle an influx of rhinos.

After a few weeks in fenced "bomas" to monitor their condition, the rhinos were released – the first to set foot in Gonarezhou National Park in nearly 30 years. Reintroducing rhinos to the park was an historic moment for Zimbabwe.

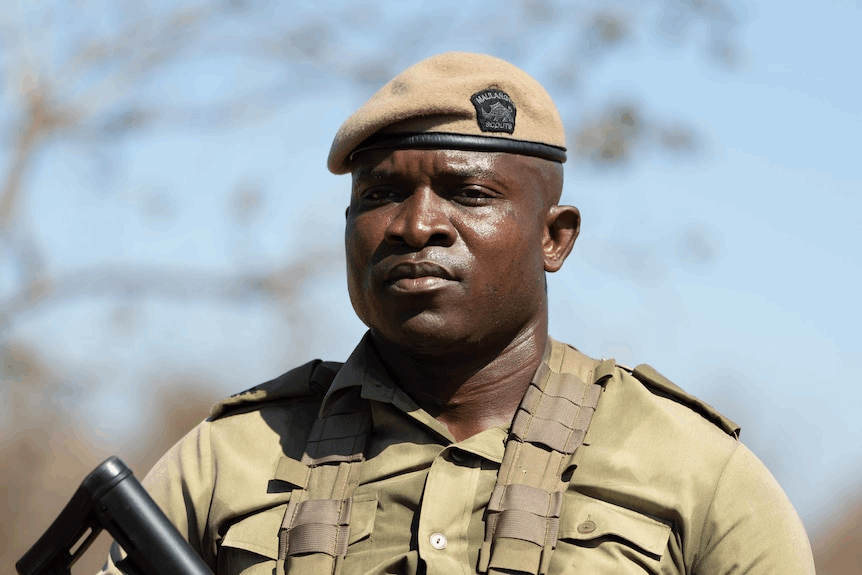

The Malilangwe Scouts

Patrick Mangondo, 42, cuts an imposing figure as he emerges from the African scrub at the head of a small column of black booted, khaki-clad men, each with an automatic rifle slung over his strapping frame.

Patrick is a sergeant in the Malilangwe Scouts, an elite anti-poaching unit and private security force tasked with protecting all the animals – and people – within the Malilangwe conservancy. "Most people see rhinos as money left on the ground," Patrick says. But rhinos have the right to live, "the right to be protected," he says.

Malilangwe hasn't been immune from the scourge of poaching over the years. Poachers have breached the park's boundary 10 times since 1998, killing and dehorning three adult rhinos during three of those incursions. A fourth rhino – a calf – died after its mother was killed in one of those attacks. On seven other occasions, Scouts foiled the attack before any rhinos could be killed.

Each day the Scouts break into groups to patrol the park's 120km fence-line on foot, monitoring for rhinos and searching for signs of poachers. Extreme dedication to fitness and physical strength is one of the demands of the job. Confronting poachers is a dangerous business. Patrick speaks of it as a war. "If they come, they'll bring war to us," he says.

It's a war that's playing out in private wildlife sanctuaries and national parks across Africa. A record 92 rangers died in 2021, half of them in homicides.

In July, the lead ranger at South Africa's Timbavati reserve, Anton Mzimba, was fatally shot outside his home in circumstances akin to a hit job. His brazen killing has stoked fears organised poaching syndicates are actively targeting wildlife protectors.

Many of the Scouts were once small-game poachers themselves. A young man named Exodus tells how he started poaching after his brother taught him how to hunt. "Most traditional people, they like to hunt," he says. "Like, culturally," he clarifies.

Many turn to poaching simply to put food on the table, targeting small wildlife species like Impala. But their tracking and bushcraft skills can be turned into assets for conservation.

Providing well-paid jobs in the surrounding villages is itself an anti-poaching strategy, says Mark Saunders. "It's one of the most often discussed phenomena in conservation circles, how to integrate communities, how to mitigate against human-wildlife conflict," he says. "We feel that education is very important and we have a bespoke conservation education camp here."

As human populations encroach further on protected areas, the potential for conflict with wild animals is only increasing. "If [local people] see an elephant in the fields, this means their crops are going to be devastated," says Sarah Clegg. "If there's a lion, there's a chance their livestock is going to be taken."

Patrick helps lead the Junior Rangers program, a community outreach initiative that brings underprivileged teens to Malilangwe to study physical fitness, bushcraft and ecology.

He's also taken an active role in training the rangers at Gonarezhou National Park in how to track, monitor and care for its new rhino population. "Individually you can't win against poaching," he says. "We need to be like brothers. You have to be a team, a strong one, to win this fight."

This article was adapted from the original By Michael Davie and Matt Henry with photography by Kyle Jira that first appeared on www.abc.net.au/

Leave Comments