Zim Now Reporters

Zimbabwe’s latest ranking on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index has once again placed it among the most corrupt countries in the world.

But what does this mean in real terms? For many Zimbabweans, corruption is not just a distant issue of high-level officials misusing public funds—it is an everyday tax on ordinary life.

To understand the daily impact, let’s follow three fictional but representative Harare residents navigating their day.

Tawanda – The Young Job Seeker

Tawanda, 23, boards a kombi from Kuwadzana into the CBD. Along the way, the minibus is stopped at a police roadblock. The conductor pulls out a crumpled $5 bill, casually handing it to the officer. No ticket is issued, no inspection is done. The money disappears into the officer’s pocket, and the kombi moves on. This cost is passed on to Tawanda in high commuter fares.

Arriving at the Registrar General’s office to apply for an ID replacement, Tawanda finds a long queue. A fixer approaches him. “For $20, I can get your application fast-tracked,” the man offers. Without the bribe, he will wait all day—possibly even be turned away.

In the afternoon, he heads to an office to drop off his CV. The receptionist looks him up and down and smirks. “Boss prefers ‘motivated’ candidates. You understand?” she hints. A bribe of $50 could secure an interview, but Tawanda, struggling with unemployment, doesn’t have that money.

Corruption Cost: $25-$75

Rudo – The Worker

Rudo, a 38-year-old accounts manager, drives into the CBD and parks in an area where parking fees are $1 per hour. She returns an hour later to find her car being clamped. “You overstayed by 5 minutes,” the municipal officer says, though she knows the real reason: an opportunity to solicit a bribe.

She can either pay the official $10 under the table or go through a bureaucratic nightmare to get her car released for almost $50 and a lot of hassle. Without the cash at hand, the cost will go up to almost $500 if her car gets towed away. She reluctantly hands over the bribe.

Later, Rudo visits a local government school to enroll her daughter. The headmaster shakes his head, telling her the slots are full—but they both know a $200 ‘donation’ will ensure placement. Desperate for her child’s education, she pays as she knows she cannot sustain private school education bills and figures the once off bribe is ultimately cheaper. This is in a country that has consistently promised free education and has failed to deliver even adequate public school infrastructure giving a rise to poorly regulated and unregistered private scams.

Corruption Cost: $210

Li Wei – The Business Owner

Related Stories

Li Wei, a 50-year-old entrepreneur, is finalizing paperwork to expand his logistics business.

He needs approval from a government regulator, but the official handling his case is evasive. Eventually, an aide pulls him aside. “Boss says $3,000 will speed things up,” he whispers. Without the payment, Li’s paperwork could sit in limbo for months. He sighs and pays.

Later, he meets a political connection at a five-star hotel. To secure a large government contract, he must make a ‘campaign contribution’ of $10,000. It’s not optional; without it, the contract will go to a politically connected competitor.

Corruption Cost: $13,000

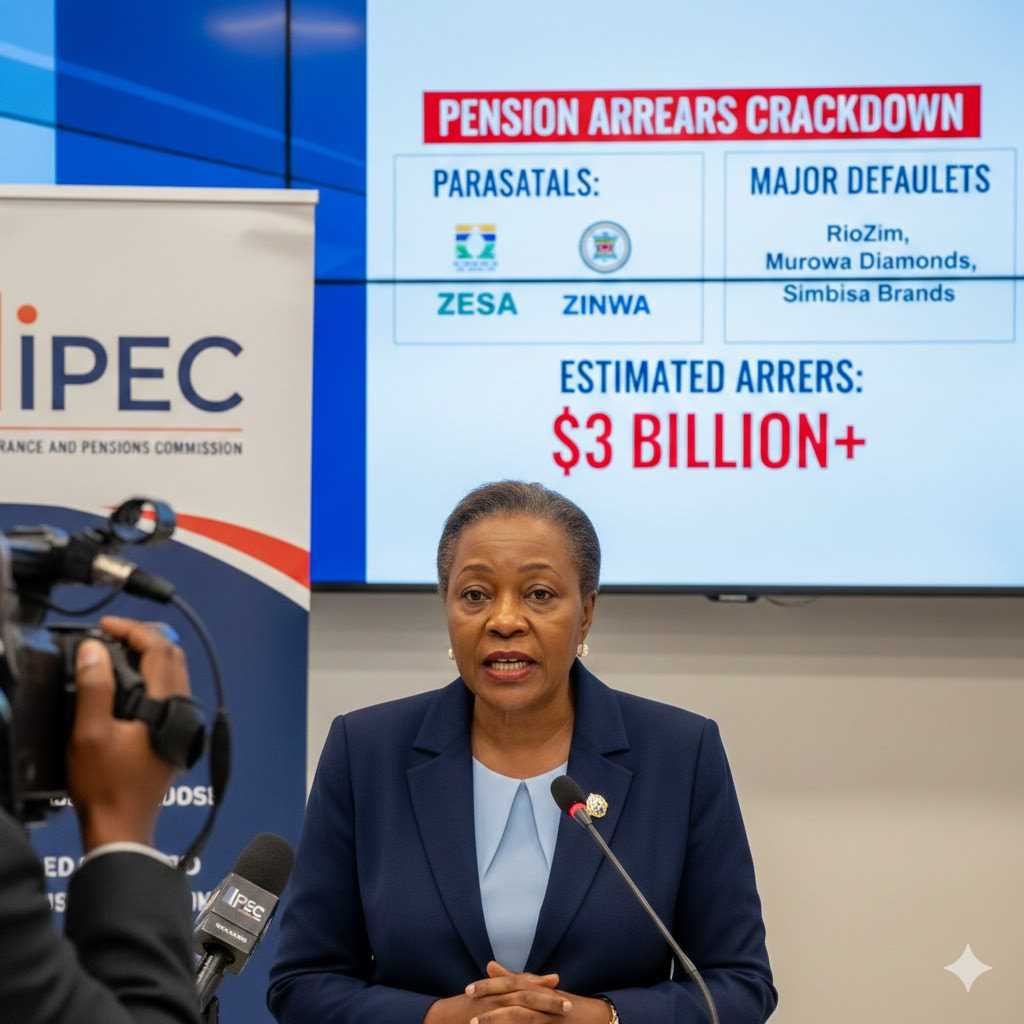

Culture of Corruption breeding death

From police roadblocks to business deals, corruption is deeply entrenched in Zimbabwe. The country has seen numerous high-profile scandals, such as the Drax COVID-19 procurement case, where millions of dollars meant for medical supplies were siphoned through inflated contracts. Similarly, the Auditor-General’s reports frequently expose ghost workers, missing funds, and questionable expenses in government ministries.

According to Transparency International, corruption costs Zimbabwe billions annually. As one local anti-corruption activist puts it: “Corruption is not just about grand looting; it is about the daily bribes that make life more expensive for everyone except the connected few.”

Ultimately the uncaptured cost of corruption is the preventable deaths of thousands each year. The poor people who depend on poorly resourced public health facilities and die because basics like oxygen and bandages are not available.

A whole generation is being lost to drugs driven to spend days loitering because of the lack of opportunities. With no jobs and no hopes, these young people are condemned to a slow but sure death as they abuse various drugs brought in by bigwigs who benefit from the corruption in the system that allows them to import and distribute drugs with impunity.

A police anti-drug campaign has netted thousands of small time pushers and users, but no real kingpin has been arrested and the problem remains a national crisis.

Learning from Others

Countries like Rwanda and Georgia have successfully tackled corruption through decisive measures that Zimbabwe could consider:

- Digitization of Government Services: Rwanda eliminated middlemen in service delivery by digitizing processes like licensing and ID issuance, reducing opportunities for bribery.

- Harsh Penalties for Corrupt Officials: Singapore imposed strict laws with real consequences for corruption, discouraging even low-level bribery.

- Independent Anti-Corruption Agencies: Botswana’s Directorate on Corruption and Economic Crime operates with real autonomy, ensuring prosecutions are not politically influenced.

- Public Participation and Whistleblower Protection: In Estonia, citizen oversight and protections for whistleblowers have helped expose and reduce corruption.

Zimbabwe has institutions like the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission (ZACC), but they need more autonomy and enforcement power. Strengthening whistleblower laws, using technology to cut out corrupt middlemen, and imposing real consequences for offenders are key steps to change.

For Tawanda, Rudo, and Li, a Zimbabwe without corruption would mean a fairer, more affordable life. But until systemic reforms take root, the hidden ‘corruption tax’ will continue to burden ordinary citizens every single day.

Leave Comments