The long-running crisis of service delivery in Harare has once again been thrust into the spotlight following recent flooding in the central business district, which left parts of the city centre submerged, disrupted traffic and exposed long-standing failures in drainage and sewer infrastructure.

The flooding, widely circulated on social media, triggered a fresh wave of public outrage and prompted Harare Mayor Jacob Mafume to publicly defend council, shifting the spotlight onto what he described as residents’ failure to meet their financial obligations to the city.

“The biggest debtors to council is the residents themselves, and they are the ones that need services,” Mafume said. “We were directed by the President to achieve minimum service delivery, and they are kneeling heavily on our necks to be able to give a certain standard of living to the residents.”

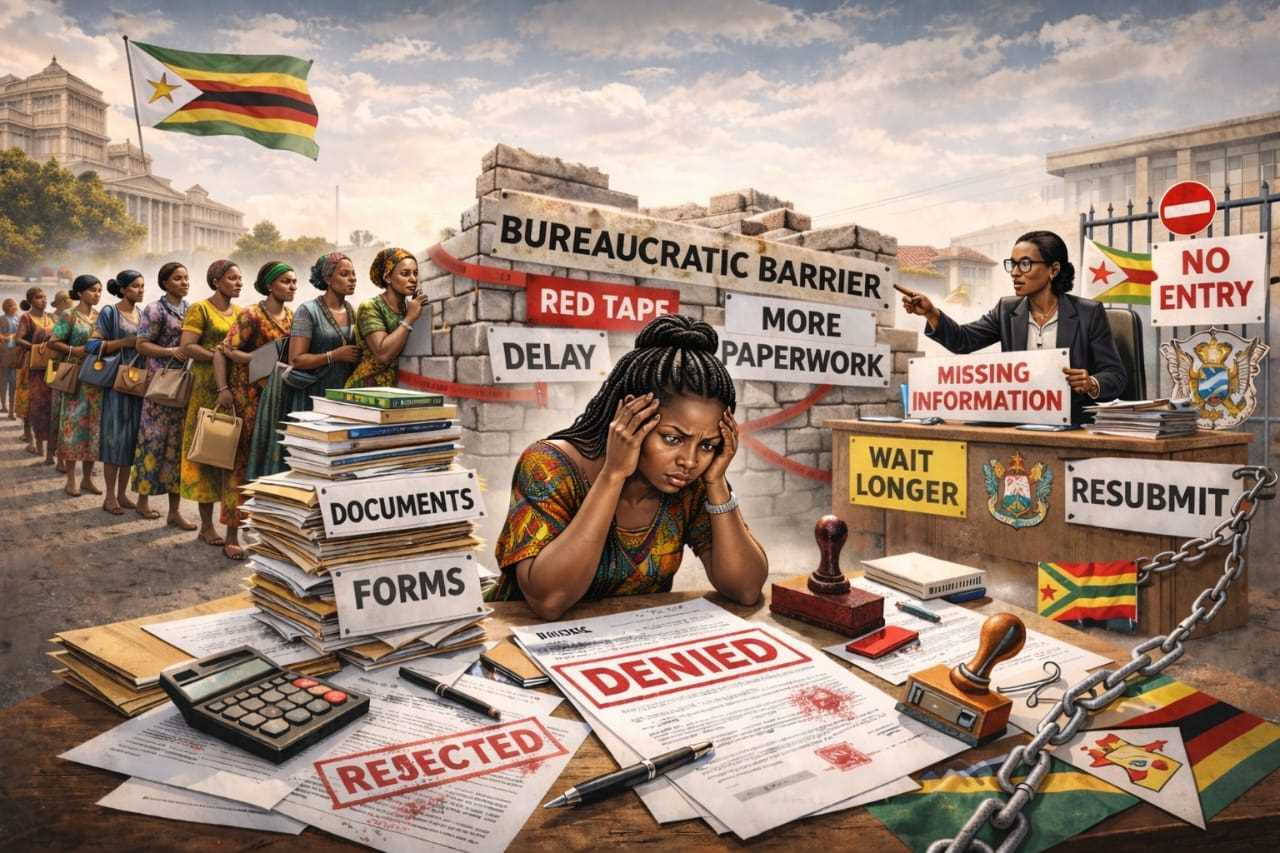

Mafume said council was under pressure to deliver services without the revenue base to support operations, arguing that the relationship between payment and service delivery was transactional.

“That is where it’s a quid pro quo,” he said. “The residents now are remaining as the bulk of debtor. They owe us about ZiG 8 billion.”

The mayor’s remarks came as residents increasingly took to social media to vent frustration over deteriorating infrastructure, particularly the state of roads across the city.

Complaints have been widespread, with Dzivarasekwa emerging as one of the most cited examples, where motorists have shared images and videos of roads riddled with deep potholes, many waterlogged and barely passable following the rains.

But residents have strongly rejected the mayor’s assertions.

Responding to Mafume’s comments in an interview with Zim Now , Harare Residents Trust Director Precious Shumba accused council of deflecting blame and ignoring its own governance failures.

“Council is delusional to make such statements, especially when looking at their internal systems where there is rampant corruption, misgovernance and wrong prioritisation,” Shumba said.

He argued that poor leadership choices within council structures were directly undermining service delivery.

“They have employed the wrong people to lead important committees, which in turn weighs down on service delivery,” Shumba said.

Related Stories

Shumba also criticised what he described as wasteful expenditure at a time when residents were grappling with failing services.

“They go on useless workshops out of Harare when the money could be used to service residents,” he said.

The exchange has resonated with many residents, particularly in high-density suburbs, who say they feel unfairly blamed for problems rooted in poor planning and mismanagement.

Dzivarasekwa, commuter Tinashe Mawoneka said the state of local roads made daily life difficult.

“Our roads are full of potholes. When it rains, it becomes dangerous,” he said. “They keep talking about debt, but we don’t see the services.”

Another resident, Memory Chikowore, said flooding and sewer bursts had become routine.

“Every rainy season the same problems come back,” she said. “Council only talks when there is public pressure.”

Town vendor Jacob Mafurere said residents had lost confidence in council’s priorities.

“If the money was really going to services, people would pay,” he said.

The standoff highlights a deepening trust deficit between Harare City Council and the residents it serves.

For council, non-payment translates into an inability to meet operational demands and political pressure from central government to maintain minimum service delivery. For residents, payment without visible improvement feels like being asked to finance failure.

Harare’s challenges are compounded by aging infrastructure, rapid urban population growth, currency instability and long-standing governance issues. Much of the city’s drainage, water and sewer systems date back decades and struggle to cope with intense rainfall, making flooding an increasingly frequent occurrence.

The recent CBD flooding has turned what was once a simmering grievance into a visible urban crisis, while social media has amplified residents’ anger, particularly over road conditions in suburbs like Dzivarasekwa.

Yet beyond the blame trading, the city appears locked in a familiar cycle: poor services discourage payment, weak revenue undermines maintenance, and accountability remains contested.

Leave Comments