Zimbabweans love the response kkkkk to a whole range of issues.

It seems like we are now conditioned to use the Korean generated digital communication response to any message that comes in and seems to be a bit funny.

Misreading of the contents based on the first few lines has resulted in some people kkkkk-ing to a message about a death in the family, or the community.

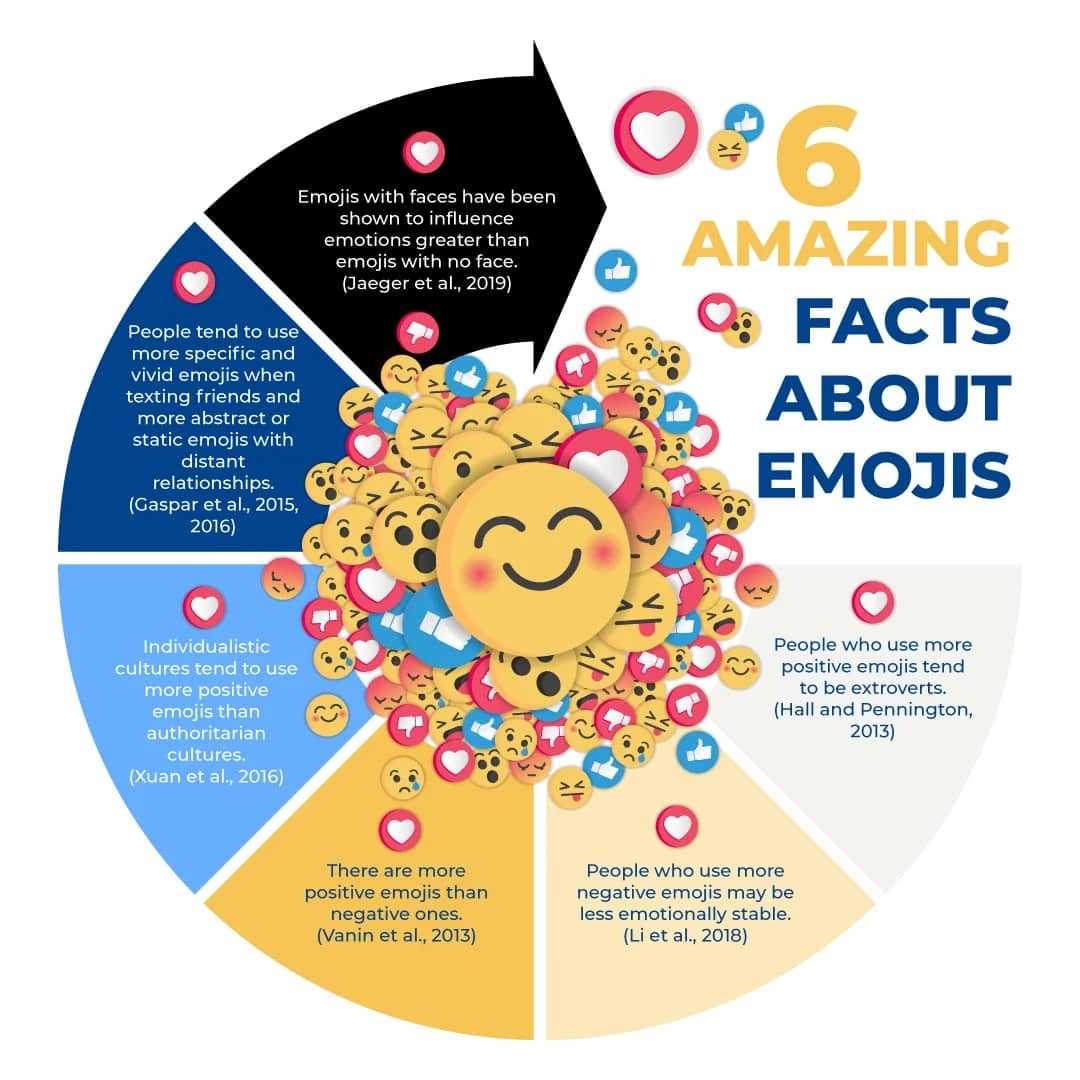

We are living in times where we are absolutely bombarded with messages and sometimes the kkkk becomes the easiest response. Social media has made this even easier with emojis.

For the older ones among us, who can relate to typewriters and VCRs and know the relationship between a ballpoint pen and a cassette, an emoji is a little diagram usually in the form of a smiley face, or other pictorial representation.

Here is an academic definition:

“The word emoji is made up of Japanese words meaning picture (e) and character (moji). The first emoji were created by Shigetaka Kurita, who borrowed the idea from weather forecasts that used symbols, Japanese characters, street signs and manga, a style of Japanese comic that -- like Western cartoons -- uses a standard group of symbols to express emotions and concepts.”

The Japanese have given the world many reasons to celebrate. They produce some durable vehicles. They took the toil out of winding watches every morning by introducing the “Japan movement” battery powered watches.

The Asian continent specializes in creating amazing machines and gadgets that make everything quicker and easier to do.

Therein lies a problem: We have taken emojis out of their Asian homeland and given them a new lease of life, with sometimes unintended consequences.

Who can ever forget the diplomat who celebrated her day in the garden with emojis of eggplant and sparked a Twitter furore that lasted all of one day. Eggplant emojis, of course, have travelled far from the garden they were inspired by and now represent a completely different type of husbandry. The same goes for assorted fruits such as the humble peach.

The quibble here is not so much about how innocent fruits and vegetables have become dangerous items to post in the woke world.

Related Stories

It is about how emojis have dulled our senses into believing we have made meaningful and caring communication by clicking and sending a little circle with a few lines on it.

In Zimbabwe we have always placed great gravity and ceremony on paying of condolences through handshaking (kubata maoko/ ukubamba izandla). The process would begin from the gate, and through the lounge where the women watched over the body, to the fireside where the men would be gathered with assorted forms of drink.

Covid-19 put a stop to this practice as funerals became hotspots, leading to people staying away from funerals, transmitting condolences remotely. The multiple handshakes were frowned upon by health authorities, hence kubata maoko/ukubamba izandla slipped away.

Some began by calling in, and having conversations, and soon this became a few lines ending with MHDSRIP. However, because we love to express ourselves in detail. (We have cousin-brothers and cousin-sisters) soon, the emoji came clicking in. The one with the tears cascading down its face, or the hands joined together in prayer (which incidentally is also a high five).

Many times the icons are dispensed quickly so the reader can swing quickly back to the various “socialites” holding live events.

“We regret to inform you that Sekuru Joe Chakuti passed away last night. He had been unwell for some time. Funerals arrangements will be released in due course,” the WhatsApp group admin posts as advised and authorised.

Immediately the emojis roll up and soon the page is loaded with little yellow marks. No-one has called the bereaved to share their grief through the phone.

Regardless which icon wins the day on the keypad, it remains that we have distilled our emotional processes into emojis.

When one is happy and celebrating, a little image of a woman in a red dress fills the screen, or that of a man in a 1980s disco dance pose.

The ease of clicking on emojis is taking away the human touch of making a call to a bereaved relative or friend and asking them how they are doing.

We can do more thank kkk-ing to issues. Let us try to communicate, or else we are quickly and easily sliding back to ancient times where we communicated with grunts, growls and sounds like kkkkkk, when we can actually express how something made us feel.

Leave Comments