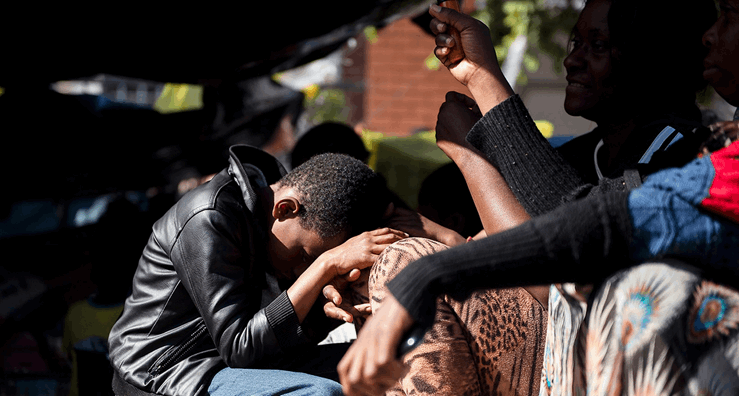

Finding a space for constructive conversation and finding a balance between conflicting interests and ideologies is super-difficult in the migration space.

By Alan Hirsch

DM -Is it possible to have a calm and sensible discussion about immigration policy? Maybe it helps when you start with a few facts — and that is where this article will start. Even then, I doubt that any readers will agree with all the positions set out.

Some numbers about people in SA

The current population of South Africa is about 60.6 million, according to a recent official estimate. The number of people living in South Africa today who were born in other countries was estimated in the 2022 Africa Migration Report to be about 4.2 million, which is about 7% of the total population. This represents the highest number of foreign-born residents living in another African country. Most are from our neighbours Zimbabwe, Mozambique, Lesotho and Malawi.

Next highest host to migrants on the continent is Cote d’Ivoire at 2.5 million. In its case, foreign-born residents comprise more than 9% of the population of 26.4 million. Like South Africa, Cote d’Ivoire has long relied on labour from surrounding countries — in its case, traditionally for the cultivation and harvesting of agricultural products.

Unemployment in South Africa is currently nearly 34%, and youth unemployment is above 60%. These numbers are extremely high by any standards. The official poverty rate is around 55%, though according to a World Bank measure set very low at $1.90 per day, around 19% of South Africans are living in poverty.

Migrants in South Africa tend to be employed in low-skilled work and the informal sector. A 2017 quarterly labour force survey found that most migrants under 44 who were working, worked in the informal sector. Migrants tend to work long hours without contracts. Though we don’t have firm data for the number of undocumented migrants, the labour market outcomes suggest that many migrants have little bargaining power and are probably undocumented.

Incidentally, the unemployment rate in Cote d’Ivoire is around 3.5%, which is extremely low by any standards, and it also has a very high labour participation rate. This means that a very high proportion of working-age people are in the labour market — much higher than in South Africa.

Debate

It is argued that migrants — in part because they tend to be self-selected, entrepreneurial people with skills and drive — add in net terms to the income of a country. Overall, there is a net benefit. The World Bank in a 2018 study found that for each migrant, two jobs were created for South Africans.

Yet, this doesn’t mean a great deal to the 34% of the labour force who are unemployed. The unemployed don’t count the number of employed people — they focus on their own circumstances. Populist politicians mobilise among the discontented poor, frequently using anti-immigrant rhetoric.

It is also sometimes convenient for the government to blame immigrants for the circumstances of the poor. Though the problem is the low rate of employment creation overall, not the foreigners, this doesn’t help the people without jobs, and it doesn’t discourage populist politicians.

Liberal thinkers and business interests defend immigration as positive for development, and human rights groups focus on the poor treatment of undocumented migrants. The liberal corner can also raise the temperature of the debate. For instance, the Financial Mail recently labelled the Minister of Employment and Labour Thulas Nxesi, “dopey Nxesi”, because of his advocacy for quotas which give preference to South African citizens in unskilled jobs, whereas the Financial Mail blames unemployment on ANC policies.

Quotas won’t even partly solve the unemployment crisis, but they may offer a temporary political salve while policies for employment growth are, hopefully, improved.

Policy issues and turnabouts

The Department of Employment and Labour issued a Draft National Labour Migration Policy for South Africa and a Draft National Labour and Migration Policy and Employment Services Amendment Bill earlier this year. The bill enables the gazetting by the minister of “a maximum quota for the employment of foreign nationals by employers in any sector”. This would be done after a process of consultation with the Employment Services Board. Certain exceptions could be made, such as foreigners employed in terms of the Critical Skills List.

It is not obvious how the quotas will be determined in conjunction with employers; how the rule will be implemented (retrospectively?), and how it will be policed. The minister has referred to higher penalties for employers who transgress: what does this mean, and will it substitute for constructive cooperation between employers and government? These are critical issues that must be debated.

Incidentally, ministers frequently say that neighbouring countries have quotas on foreign workers. I found that this was true in only three of our SADC partners: Mozambique, Angola and the DRC.

The real problem Nxesi is trying to address is that basic standards of employment are not, and maybe cannot be, effectively policed in South Africa. More than 55% of migrants work in jobs where no UIF is deducted, and more than 40% of migrants work in jobs without any employment contract. This is illegal. In an ideal world, maintenance of employment standards would obviate the need for migration quotas.

Related Stories

Visit Daily Maverick’s home page for more news, analysis and investigations

A Critical Skills List was issued in February 2022, updating a list issued eight years earlier. Migrants with designated skills are encouraged to migrate to South Africa and get virtually automatic permission to work and live in the country. In response to protest that key medical skills were left off the list, Home Affairs Minister Aaron Motsoaledi issued a supplemented list in August, but the list remains limited.

In the 2017 White Paper on Immigration, Cabinet decided to replace the critical skills list with a points system such as that used in Canada and Australia. It is not clear why the White Paper has been ignored.

Another pressing immigration issue is the Zimbabwe Exemption Permit. Until 2017, Zimbabweans who had moved to South Africa before or during 2009 because of conditions in Zimbabwe, were permitted to remain under the Dispensation of Zimbabweans Project (DZP).

In 2014, this was converted to the Zimbabwe Special Dispensation Permit (ZSP). In 2017, the ZSP was withdrawn and replaced with a Zimbabwean Exemption Permit (ZEP) which allowed the same Zimbabweans to remain in South Africa under special permission until the end of 2021.

Towards the end of 2021, South Africa announced that Zimbabweans who lived in South Africa under ZEP regulations would have until the end of 2022 to either apply for regular visas to remain in South Africa or to leave South Africa.

Zimbabweans living under the ZEP do not include those who migrated formally or informally since 2009. There are only 178,000 of them, including children born in South Africa during their stay. Aside from children, these people have been in South Africa for at least 13 years.

Minister Motsoaledi responded to concerns that Home Affairs could not process all 178,000 fairly by the end of 2022 by extending the exemption period to the end of June 2023. But we should question whether it is fair to subject them to a sifting process, between those allowed to remain and those who must return to Zimbabwe — 13 years is a long time and 178,000 is a relatively small number.

Other delays this year were partly because, having uncovered extensive corruption in the permit section of the DHA, the minister removed corrupt permit officials and had to replace them. The minister recognised the backlogs and provided extensions on existing permits.

A textbook on migration says that what governments say about immigration and what they do about it, is frequently poles apart. The rhetoric might be aggressive, actions are frequently less so.

Facing conflict, embarrassment and a court case, Minister Motsoaledi made considerate amendments to rules. Yet, this doesn’t help Zimbabweans living in SA under the ZEP who now apply for jobs under circumstances of great uncertainty. Rhetoric, under conditions of uncertainty, has a power of its own.

Broader African issues

South Africa and several middle-income neighbours have not participated in continental initiatives to reduce barriers for Africans crossing African borders. Visa-free travel across most SADC borders, and the recent agreement between Namibia and Botswana to liberalise controls over their mutual border, are positive and exciting for the southern African region.

But, in general, we and our neighbours are excessively cautious in respect of liberalising or even modernising border management for other Africans.

Conclusion

Finding a space for constructive conversation, and finding a balance between conflicting interests and ideologies, is super-difficult in the migration space. In circumstances where domestic unemployment and poverty are excessively high and populist politics is widespread, this is virtually impossible.

Nevertheless, we should be looking for practical solutions rather than raising the temperature of the debate. Those solutions should be based on evidence, not conjecture, using actual migration data and evidence of how other countries have successfully addressed these challenges.

Prof Alan Hirsch is founder and director of the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance at the University of Cape Town. He is currently leading a new research programme on migration governance in Africa based at GAPP (Government and Public Policy), the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance and SOAS. He was a member of the Department of Trade and Industry in 1995 managing industry and technology policy, and moved to the Presidency in 2002. He is a member of the Presidential Economic Advisory Council.

This article first appeared on Daily Maverick

Leave Comments