Monica Cheru-—Managing Editor

“It took sacrifice for China to achieve its phenomenal development and pull itself out of poverty,” said Professor Wang Sangui of Renmin University in Beijing.

That sacrifice came in the form of exclusion. China’s hukou system deliberately limited rural migrants from accessing urban education, healthcare, or housing—even as they laid the foundation for China’s economic rise.

For decades, rural workers built cities they could never truly inhabit. They were the invisible engines of an extraordinary transformation that created a middle class of over 400 million people—larger than the entire population of the United States.

But China didn’t stop at economic growth. Through determined poverty alleviation policies and rural revitalization strategies, it lifted 800 million people out of poverty.

In 2024, China produced a record 706.5 million metric tons of grain, expanded rural tap water access to 87%, and pushed farmland mechanization rates above 67%.

The welfare of the rural population is a key focus for the government, according to the reports and resolutions of the 2025 Two Sessions held in Beijing this March.

President Xi Jinping’s 2020–2035 Rural Revitalization Strategy signals deep structural commitment—not just token reform.

It’s tempting to see this as a model Africa might emulate. But as Professor Wang Yiwei, also of Renmin University, warned, “Africa should not look to copy and paste China’s model. It is just an inspiration.”

Africa’s More Complex Puzzle

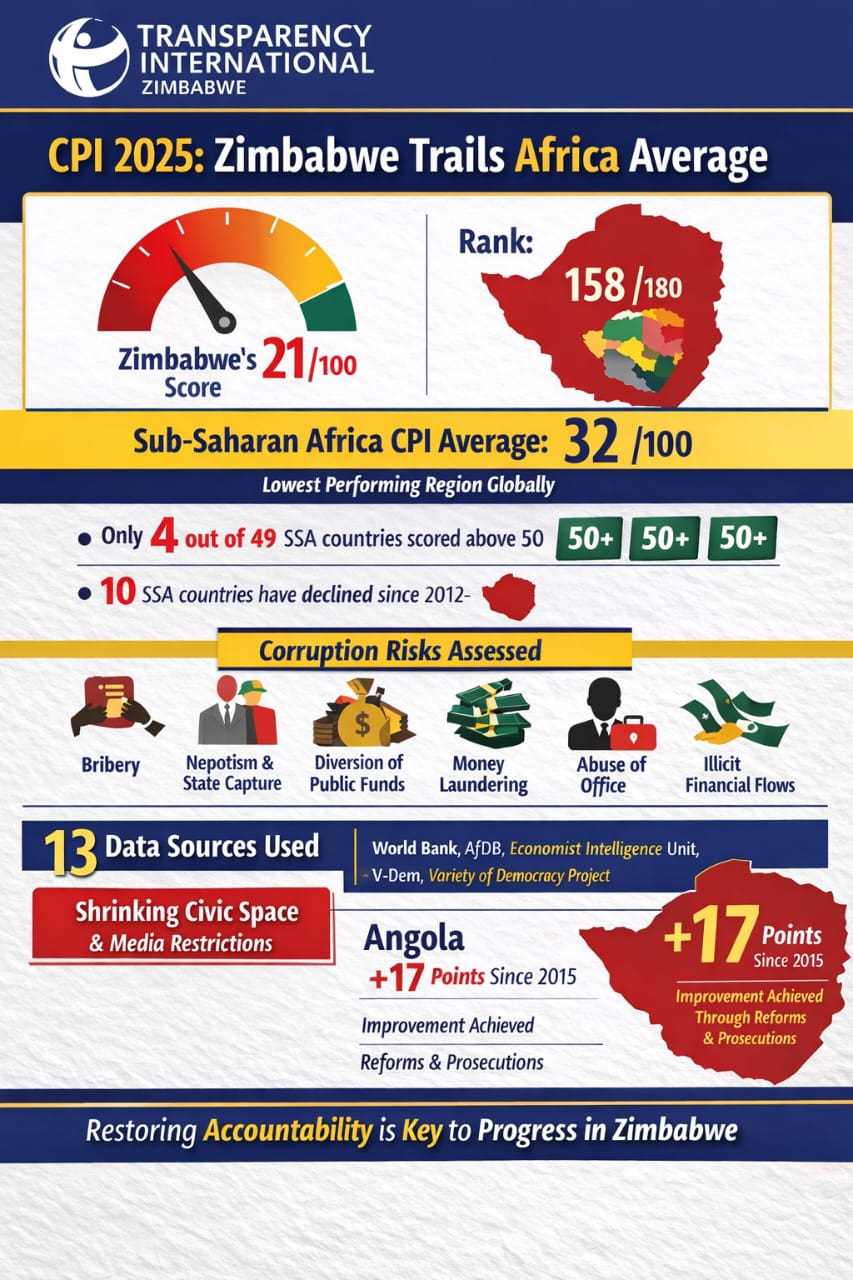

Professor Wang Yiwei pointed out that Africa does not enjoy China’s centralized command structure. Instead, many African nations are mired in fragile democracies, where short-term political cycles undermine long-term development planning.

“It is not a coincidence that Rwanda, which enjoys political stability and strong leadership, is progressing well,” said Professor Wang Yiwei.

Moreover, the continent is still reeling from decades of Western-imposed structural adjustment programs, which left economies vulnerable and people impoverished.

According to the World Bank (2024), Sub-Saharan Africa accounts for 16% of the global population but 67% of people living in extreme poverty. Nearly half of its rural population lives in deep deprivation.

Chinese investment has undeniably brought real progress: 100,000 km of roads, 10,000 km of railways, and 100 ports built across Africa. Mining and infrastructure projects have created jobs and spurred trade. But these gains are uneven and insufficient. Extractive development alone won’t meet the continent’s social and economic needs.

As Amina Mohammed, UN Deputy Secretary-General, stated: “Investment in Africa must go beyond extracting raw materials… It must build the roots of a modern economy, hard and soft infrastructure alike, and this must include bold investments into Africa’s strongest asset—its people.”

The Tension Between Progress and Protest

Africa’s challenge is not just economic—it’s cultural and political. The continent must reconcile activism, democracy, land rights, and history with the hard realities of development.

In Nigeria, the #EndSARS movement channeled national frustration with police brutality and economic exclusion. In Kenya, Chinese-funded rail projects faced resistance due to land disputes. Ethiopia’s Hawassa Industrial Park, modeled on China’s special economic zones, saw its promise of jobs overshadowed by protests against displacement.

Related Stories

Such protests are often triggered by genuine grievances but often hijacked by activists who do not want to see progressive resolution. Yet when activism halts development without proposing alternatives, communities are left in limbo—still poor, still waiting. NGOs frequently exit after the headlines fade. The affected populations, meanwhile, remain stuck without jobs, infrastructure, or hope.

Criticism is easy. Solutions are hard

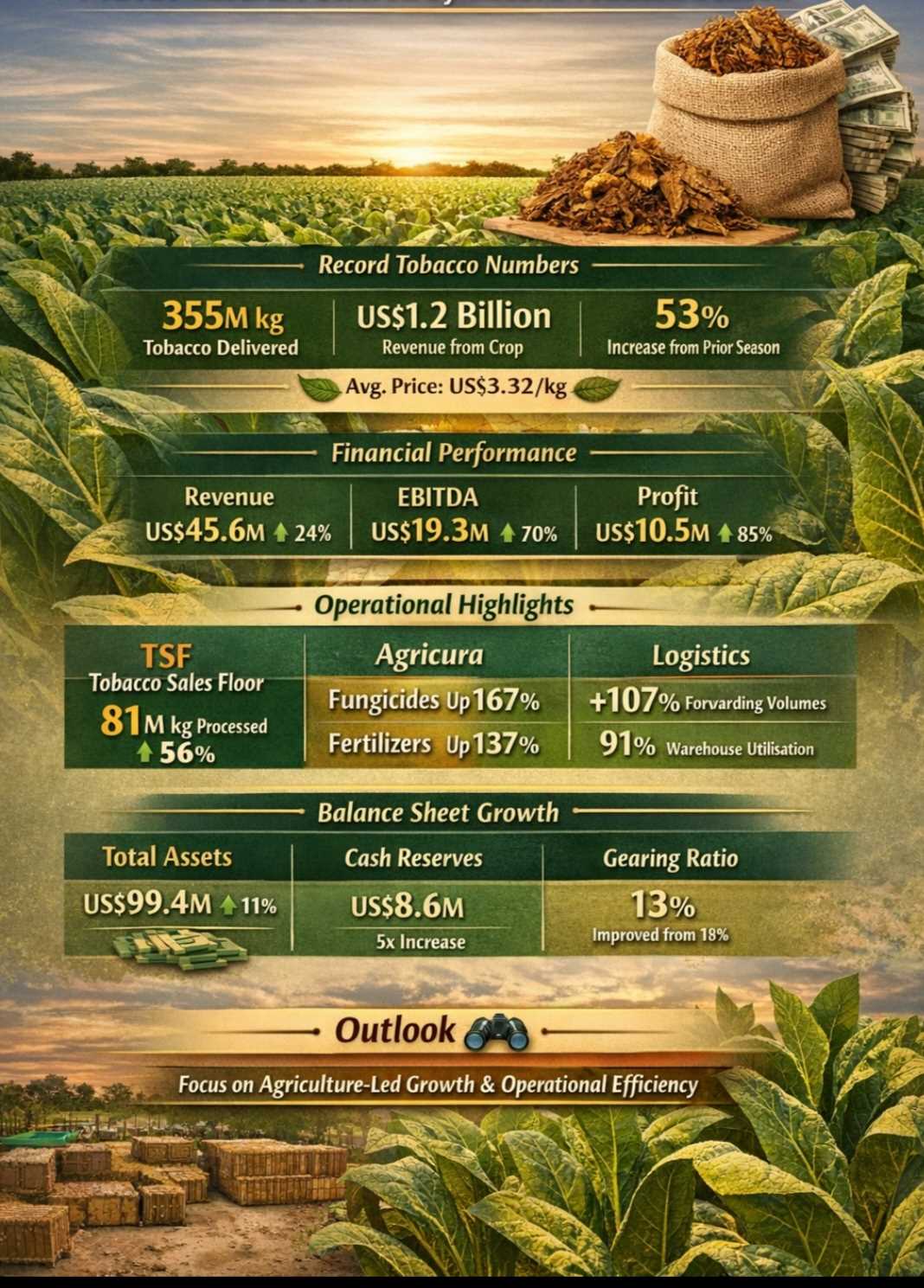

In Zimbabwe, watchdogs like the Zimbabwe Environmental Law Association and the Centre for Natural Resource Governance often highlight exploitation by Chinese investors.

But they rarely offer scalable development alternatives. Their advocacy, while important, creates a vacuum that can deepen poverty if not coupled with viable plans for inclusive growth.

“We cannot be talking just about democracy, transparency, and good governance,” said Serge Mombouli, Congo-Brazzaville’s ambassador to the U.S. “At the end of the day, the population does not have anything to eat… People do not eat democracy.”

Africa cannot afford purity politics. It needs deals—pragmatic, well-negotiated ones—that defend national interests while delivering local benefits.

Learning Without Imitating

The Botswana model offers one such example. Transparent diamond revenue management built roads, schools, and hospitals—combining foreign capital with sovereign control and institutional trust.

Zimbabwe’s nationalistic rallying cry, “Nyika inovakwa nevene vayo” (a country is built by its people), resonates deeply. But slogans don’t build steel mills. Infrastructure and industry require capital, coordination, and compromise—elements often missing in the region’s political calculus.

Tanzania’s “rural cities” initiative offers a more grassroots alternative. By trying to create economic hubs in rural areas, it slows urban migration and retains community cohesion. The process is slow—but democratic and deliberate.

Wanjira Mathai, Kenyan environmentalist and daughter of Nobel Laureate Wangari Maathai, calls for industrialization at home: “We need to process our raw materials here in Africa… build wealth for small farmers and foster a fairer and more equitable economy.”

China's path worked, but it is not Africa’s

The world today is not the one China navigated in the 1980s. Africa faces hyper-globalization, climate risks, donor dependency, and rising youth unemployment—all under governments often distrusted by their own citizens.

Fast, inclusive development is essential. But it won’t come from copying anyone else.

Tony Elumelu, founder of the Tony Elumelu Foundation, offers a fresh vision: “Africapitalism is about the intersection of economic prosperity and social wealth… of making profit and doing good, and not waiting to finish one before you do the other.”

This is the synthesis Africa needs: strategy over slogans, equity over extraction, and accountability on all fronts—whether to investors, activists, or governments.

Western-funded NGOs must be judged by long-term outcomes, not moral posturing. Chinese models should be studied, not mimicked. And African leaders must rise beyond rhetorical nationalism to execute serious, sustained development strategies.

Because ultimately, it’s not about whether China was too harsh or whether activism is too loud. It’s about whether Africa is bold enough to chart its own course—and build accordingly.

Leave Comments