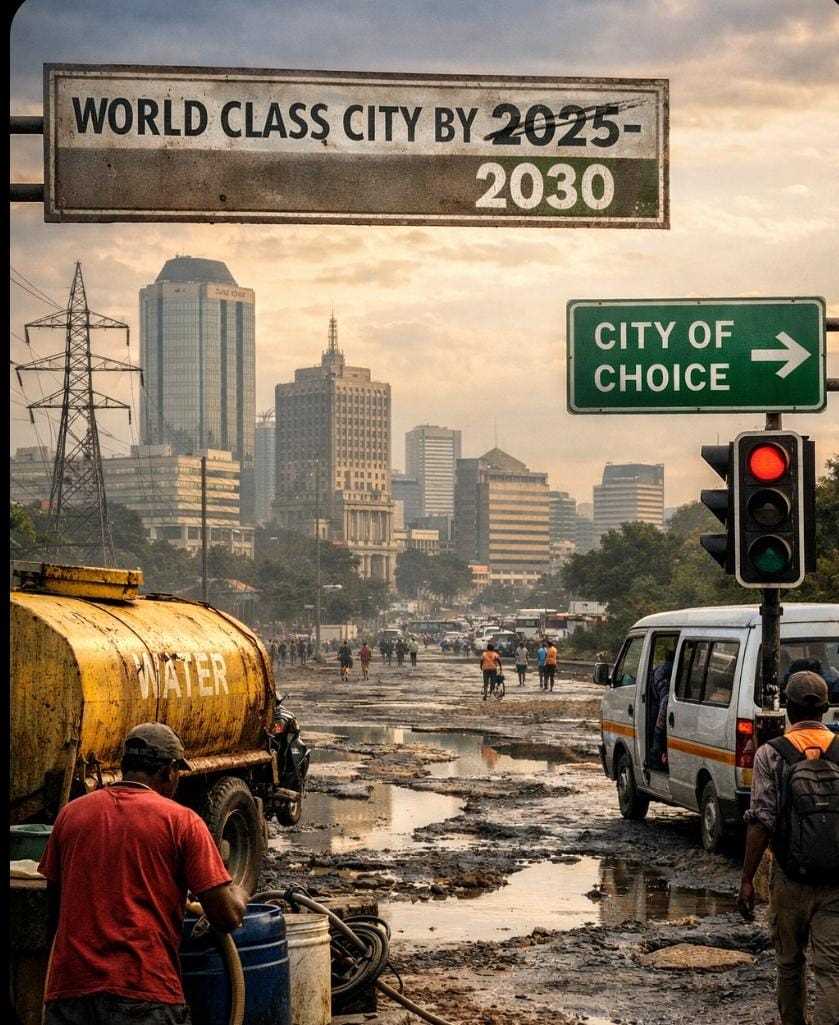

In a country where everything, including Top Soup, now costs a chant 4 ED, the ingenuity of the Zimbabwean imagination remains undefeated.

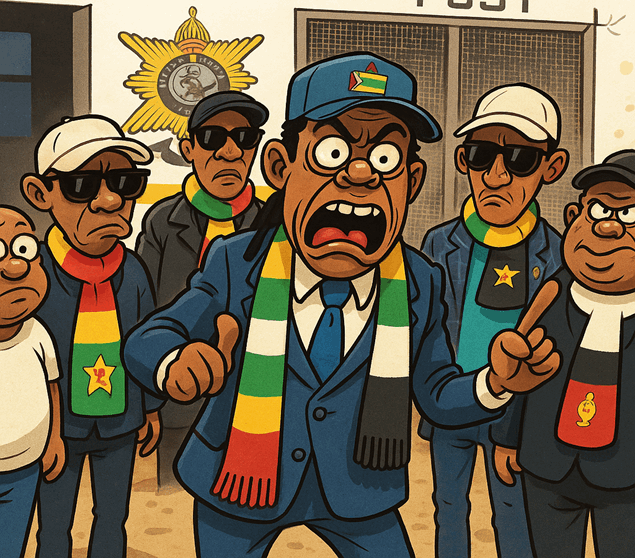

We’ve survived miracle money, pavement gold, and municipal invoices written like breakup letters. But now we have something truly pioneering: the Zimbabwe Anti-Presidential Criticism Team—an outfit so self-important that satire doesn’t need to exaggerate anything.

Yes, we know people are spending nights awake trying to figure out how they win the car lottery, but this group has taken their overt begging drive to the basement.

Their mission, as they proudly proclaim, is simple: work with the Zimbabwe Republic Police to arrest anyone who criticises the President. Not threatening harm. Not inciting violence. Just… criticising. In their worldview, critique equals insult, and the Constitution is a kind of comfort blanket—you hold it up, but you never actually read past the cover.

Fine. Let’s read it for them.

Section 61 of the Constitution of Zimbabwe is not ambiguous. Every person has the right to freedom of expression, to receive and communicate ideas and opinions—even the ones government finds unflattering.

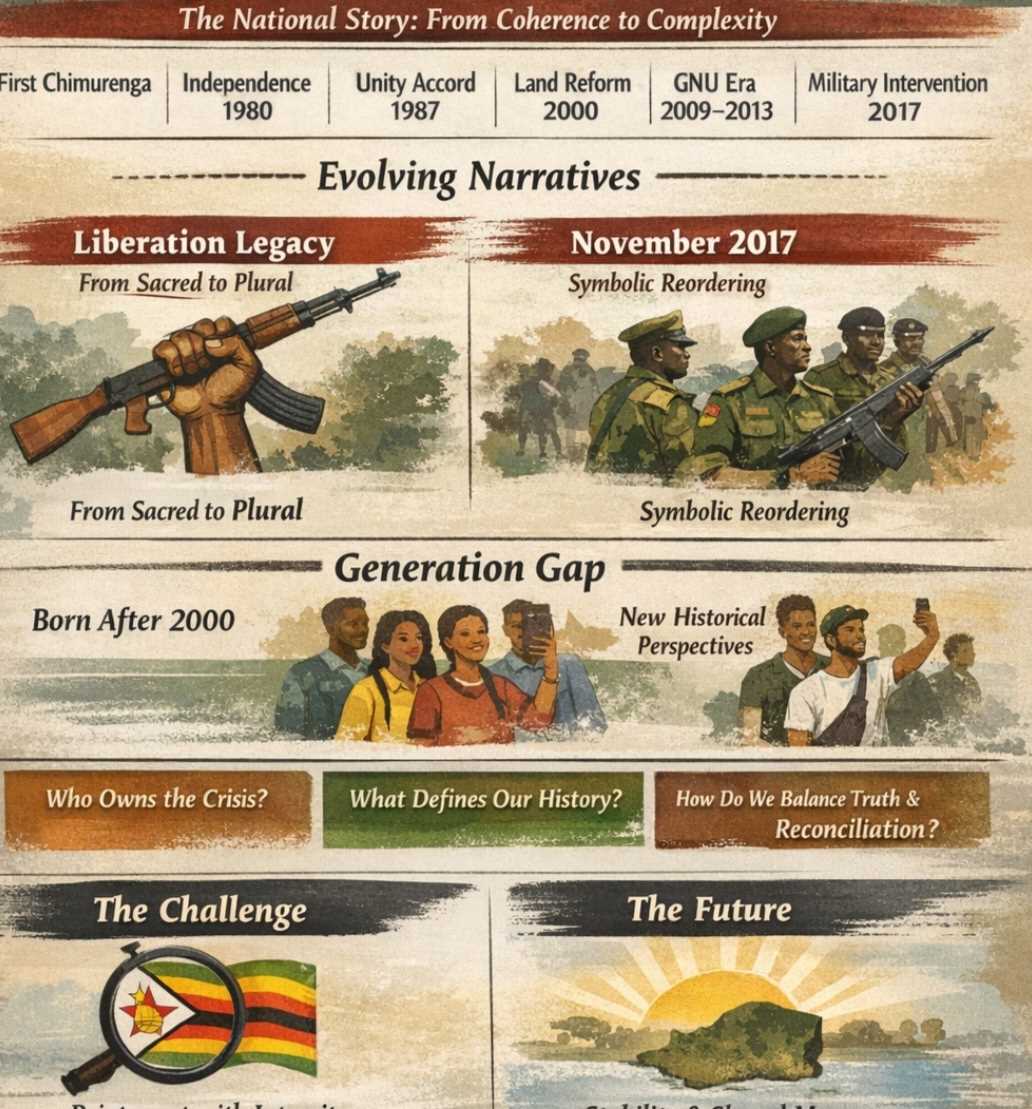

The same section explicitly abolished the old offence of “insulting the President,” a colonial relic repealed because it violated democratic norms and was routinely abused. In 2013 alone, dozens were arrested under that offence; its removal was intentional and constitutionally entrenched.

Related Stories

So the very right this new “team” wants to criminalise is the one the Constitution protects most clearly. And the authority they claim—imaginary arrest powers for hurt feelings—is not one the ZRP possesses. Policing powers come from statute, not from social media press conferences. The Constitution does not bend because a group of overzealous patriots discovers a new weekend hobby.

In any functioning republic, public officials—especially Presidents—are not shielded from scrutiny; they are its primary targets. Courts everywhere, including our own, recognise the difference between criticism (protected), insult (mostly protected), and defamation (handled in civil court, not cells). When state actors become allergic to scrutiny, that’s no longer governance—it’s personal insecurity subsidised by public institutions.

This new Anti-Criticism unit, for all its theatrical seriousness, exposes a deeper national reflex: a preference for narrative management over delivery, for performance loyalty over accountability. It is governance by choreography—set the stage, cue the applause, and threaten those who say the performance is off-key.

A Presidency grounded in confidence doesn’t outsource its ego. It doesn’t need auxiliary enforcers patrolling emotions. It relies on transparency, service, and constitutional order—not fan clubs with imagined badges.

And while most of this noise will collapse under actual law, the real danger is implicit: the normalisation of anti-democratic reflexes. The ominous message that citizens must whisper. That critique is rebellion. That silence is safer. Democracies rarely collapse in one dramatic moment—they shrink through a steady erosion of what citizens think is lawful to say.

Zimbabwe’s Constitution is clear. The courts are clear. Regional norms are clear. And civic common sense is even clearer: Criticism is not a crime. Scrutiny is not sabotage. Demand for accountability is not an insult.

If anything needs defending today, it is not the office of the President—it is the public space in which citizens speak.

And if this new outfit insists on patrolling opinions, they may discover an uncomfortable truth: the Constitution they claim to protect stands firmly between them and the handcuffs they fantasise about.

For their sake, someone should read it to them.

Leave Comments