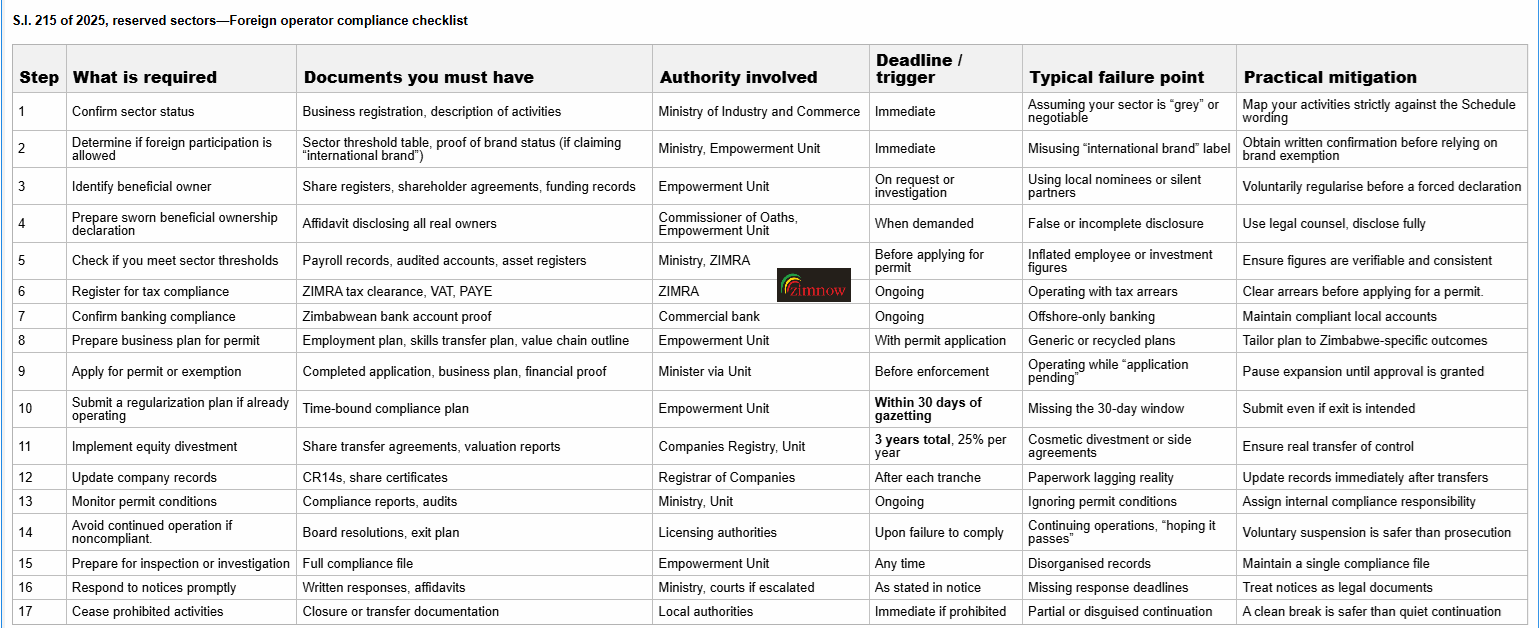

The gazetting of Statutory Instrument 215 of 2025 marks a decisive shift in how Zimbabwe intends to structure ownership and participation in certain parts of its economy. While much of the attention has focused on what the regulations mean for foreign investors, the more important story is what they signal for local businesses and entrepreneurs.

At its core, the new framework is designed to ensure that sectors identified as “reserved” genuinely deliver ownership, income, and decision-making power to Zimbabwean citizens, rather than functioning as entry points for external capital operating indefinitely at the retail and services level.

Why government is drawing firmer lines

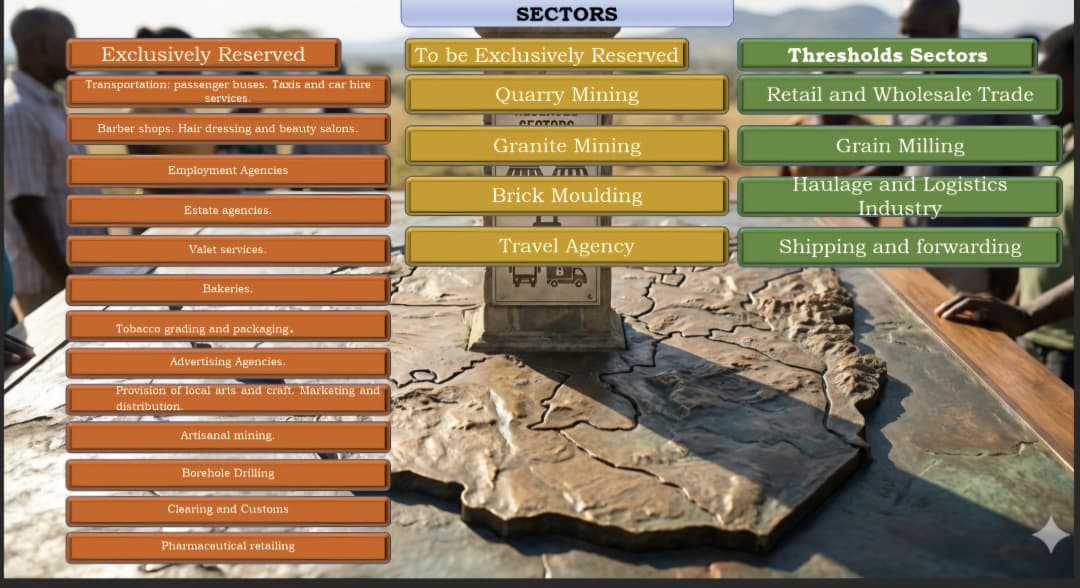

For years, Zimbabwe has encouraged foreign investment alongside policies aimed at empowering local participation. In practice, this has produced uneven outcomes. While large, capital-intensive sectors such as mining and manufacturing have continued to attract foreign capital, everyday commercial sectors have increasingly seen local entrepreneurs crowded out by better-capitalized foreign operators.

S.I. 215 of 2025 represents an attempt to rebalance that equation. It identifies specific sectors where the government believes local ownership should be dominant and clarifies, with far greater precision, where foreign participation is no longer appropriate or should be strictly limited.

The regulations create clearer space in sectors such as retail trade, transport services, advertising, estate agencies, bakeries, tobacco grading, and other service industries. These are sectors where local businesses have often complained of being unable to compete on equal terms with foreign-backed operations.

By reserving these areas primarily for Zimbabweans, the policy aims to protect local enterprise, encourage domestic capital formation, and retain profits within the country. For businesses that already operate in these sectors, the regulations provide greater certainty about who their long-term competitors will be.

In sectors where foreign participation is still allowed under strict thresholds, the intention is to ensure that only large-scale investments with clear employment and value-chain benefits remain, rather than small or medium operations that mirror what local entrepreneurs can already do.

The transition period and regularisation

The regulations recognize that the economy cannot be restructured overnight. Businesses that were already operating when the instrument was gazetted are given a defined transition period to regularize their position.

This includes submitting a regularization plan and, where required, restructuring ownership or operations over a three-year period. The intention is not abrupt disruption but a gradual realignment of ownership patterns in line with policy objectives.

What Zimbabwe’s New Indigenisation Rules Mean for Chinese Restaurants and Small Retail Shops

Restaurants are not explicitly listed by name in the schedule of reserved sectors. However, in practice, most Chinese restaurants fall under retail trade, particularly where their operations involve the sale of food and beverages directly to the public at a modest scale.

Most Chinese restaurants and small retailers operating in Zimbabwe, whether independent family businesses or small chains, do not meet the thresholds of 200 employees and a US$20 million investment. This means they now fall into a sector where foreign participation is no longer permitted at their scale.

A small shop employing a handful of workers and operating from a single storefront, even if fully tax-compliant and openly registered, does not qualify to remain foreign-owned under the new framework. The regulation is not making a judgment on how the business has operated in the past. It is redefining what is allowed going forward.

Why openness does not equal exemption

Related Stories

It is important to note that most Chinese restaurants and retail shops have been operating openly. They are known to local authorities, registered with tax authorities, and often employ Zimbabwean staff. Many also complied with company law requirements by appointing a resident public officer.

S.I. 215 of 2025 does not suggest these businesses were operating illegally. Instead, it represents a policy shift that changes the rules of participation in certain sectors. Past compliance does not automatically grant permission to continue under the new framework.

What options are realistically available

For small Chinese restaurants and retail shops, the options are limited and difficult.

Scaling up to meet the retail threshold of two hundred employees and twenty million dollars in investment is unrealistic for most. Applying for a permit is therefore not a viable path in most cases.

This leaves three practical possibilities. The first is genuine divestment, where ownership and control are transferred to Zimbabwean citizens, with the foreign owner exiting or retaining a strictly limited role outside the reserved sector.

The second is repositioning, where the business shifts into activities not classified as retail, although this will require careful scrutiny to ensure compliance.

The third is an orderly exit, where operations are wound down over a defined period. Each of these paths carries financial and emotional weight, particularly for long-established family businesses.

Why the regulations close the door on proxies and nominee arrangements

The regulations are clearly designed to prevent a foreseeable risk arising from the policy shift.

As sectors become reserved, there is a danger that some foreign operators may attempt to retain control by placing businesses in the names of Zimbabwean citizens who act only as proxies or nominees. In such arrangements, local individuals are paid a fee or offered token shareholding, while real control and benefit remain elsewhere.

S.I. 215 of 2025 directly addresses this risk by empowering authorities to look beyond formal registration and require disclosure of the true beneficial owners of a business. This is intended to ensure that local ownership is substantive, not cosmetic, and that empowerment does not become a paper exercise.

For genuine Zimbabwean and foreign enterprises, the regulations offer both opportunity and responsibility. While the policy creates space for local ownership, it also demands that any partnerships or shareholding arrangements reflect real participation, decision-making power, and economic benefit.

Leave Comments