Simbarashe Namusi

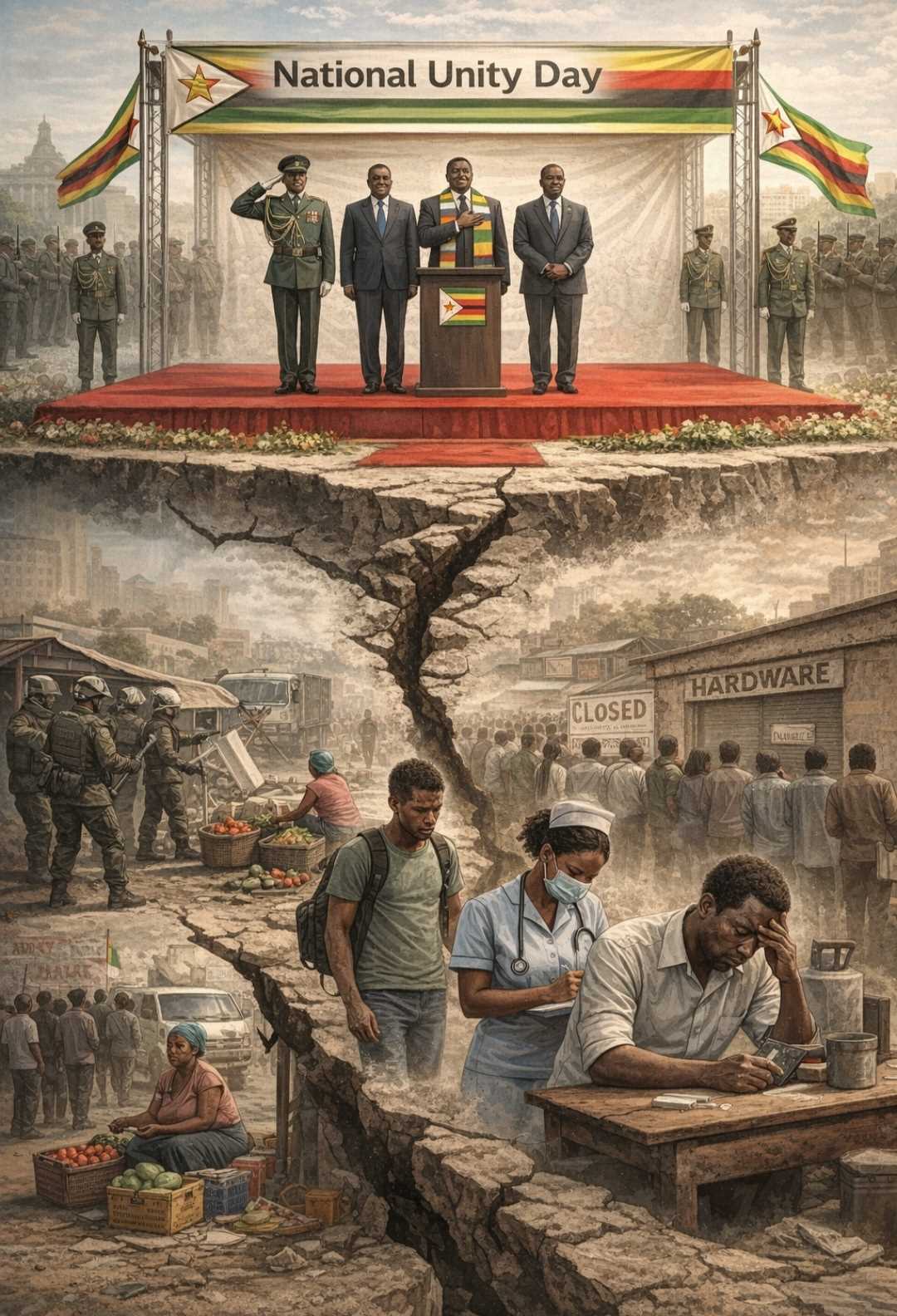

Every December 22, Zimbabwe marks National Unity Day with solemn speeches and carefully choreographed ceremonies.

The day commemorates the 1987 Unity Accord, a political settlement that ended open conflict and reshaped the country’s post-independence trajectory.

Yet long after the formalities fade, a persistent question remains: are we marking genuine unity or merely repeating a ritual?

For many Zimbabweans, Unity Day feels more symbolic than transformative. It is acknowledged rather than felt. While the accord closed a chapter of armed confrontation, it did not resolve the deeper wounds that made unity necessary.

Nearly four decades later, the absence of a comprehensive, credible truth-telling process continues to cast a long shadow over national reconciliation.

Unity, after all, is not declared. It is built.

In Matabeleland and parts of the Midlands, the legacy of Gukurahundi is not distant history. It lives in unmarked graves, broken families, and silences passed down through generations.

Although the state has, in recent years, acknowledged the need for healing, progress remains uneven and uncertain. The National Peace and Reconciliation Commission, constitutionally mandated to guide this process, has struggled to inspire public confidence.

Consultations have been patchy, outcomes unclear, and many victims feel their pain is being managed rather than meaningfully addressed.

Without truth, unity becomes performative. Without justice, calls for closure sound like demands for silence.

Contemporary politics further strain the unity narrative. The country remains deeply polarised, with divisions sharpened by contested elections and a narrowing civic space. Disagreement is often framed as disloyalty, while political identity can shape access to opportunity, security and voice.

In such an environment, unity risks becoming a slogan used for discipline rather than a value nurtured through inclusion.

Related Stories

Recent years have offered repeated reminders of this fragility. Selective application of the law, uneven policing of public gatherings, and intolerance of dissent continue to erode trust in national institutions.

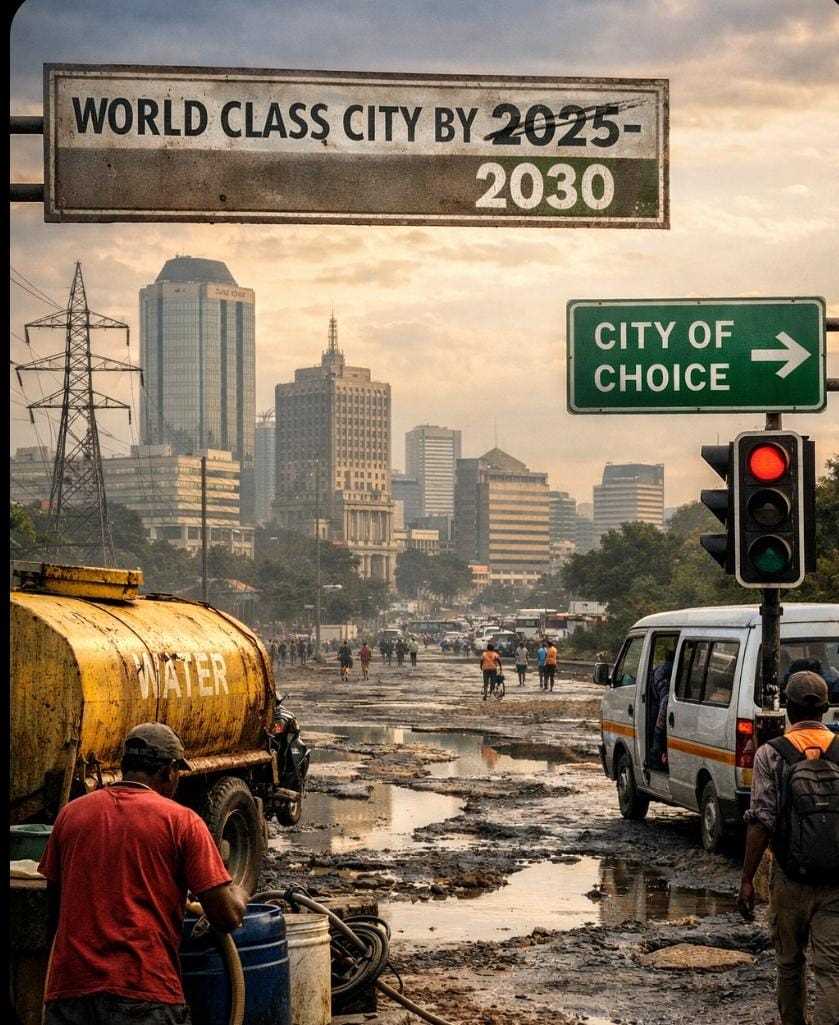

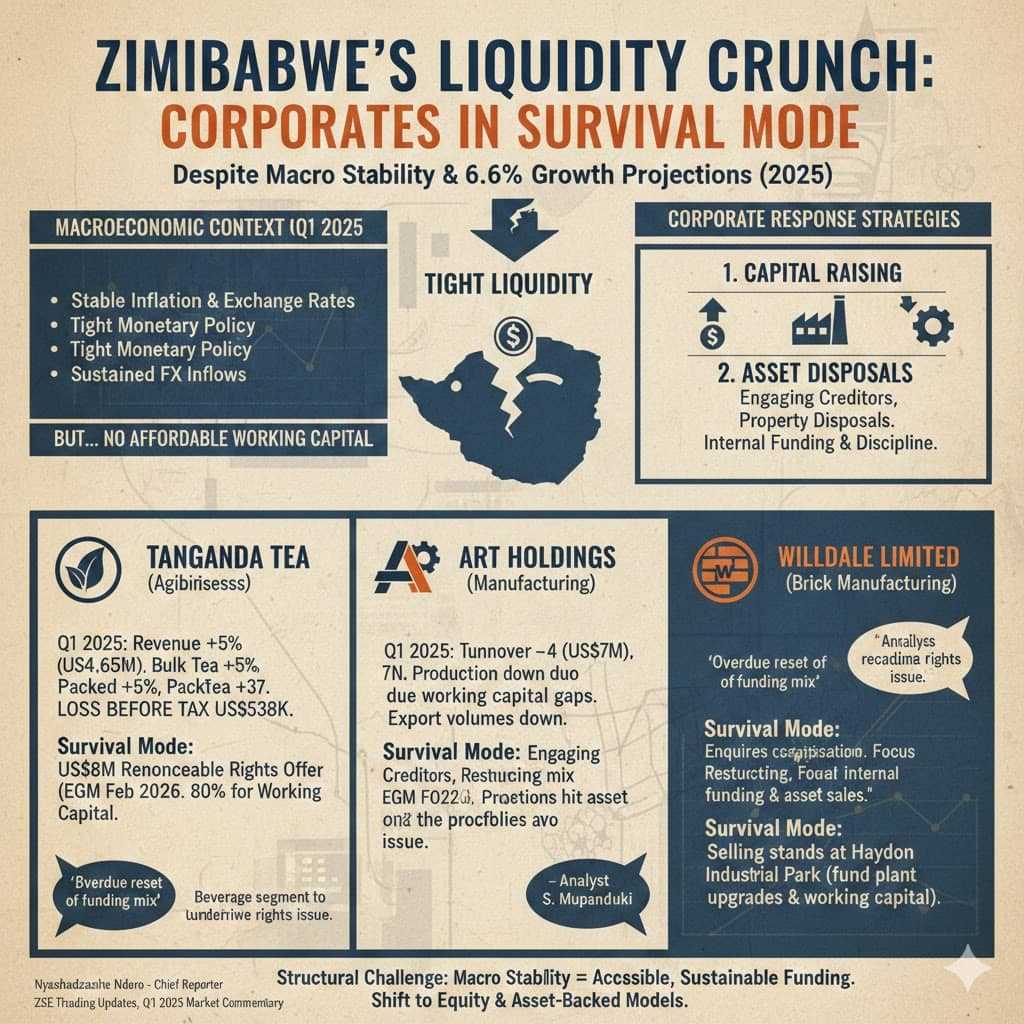

Unity can not flourish where citizens feel unequally protected or unheard. Economic realities deepen these divisions. For a few, Unity Day is a public holiday marked by official functions.

For many others, it is simply another day of survival: the informal trader displaced from the CBD, the graduate navigating years of unemployment, the nurse striking for a living wage, the teacher buying chalk from their own pocket. These experiences are not peripheral. They shape how citizens relate to the state and to one another.

A nation can not feel united when dignity itself feels unevenly distributed.

There is also the problem of selective unity. Calls for cohesion often grow loudest during moments of external criticism or international scrutiny. Yet internally, differences of region, language, and political belief are routinely exploited for short-term political gain. Unity becomes a shield when convenient, then quietly abandoned when it demands accountability, reform, or redistribution.

This is not to dismiss the historical significance of the Unity Accord. Ending overt violence mattered. Peace, even imperfect peace, is not nothing. But peace without justice is a pause, not a resolution. Genuine unity requires more than the absence of conflict. It requires equity, accountability, and the courage to confront uncomfortable truths.

What would real unity look like?

It would begin with honesty: a transparent and credible truth-telling process that centres victims rather than political reputations. It would include deliberate development in historically marginalised regions, not as charity but as redress. It would protect the right to dissent, recognising that disagreement is not the enemy of unity but a sign of democratic maturity.

Most importantly, unity would be felt in everyday governance: in fair and impartial policing, in equal application of the law, in public institutions that serve citizens rather than parties, and in an economy where progress is shaped by effort and innovation rather than proximity to power.

Until these conditions are met, National Unity Day risks remaining a well-rehearsed performance — a national ritual that asks citizens to applaud while standing on unresolved pain.

Zimbabweans are not opposed to unity. They yearn for it. But they seek a unity that is lived, not lectured; one that confronts the past honestly, reforms the present meaningfully, and offers a believable future.

Unity is not a holiday. It is hard work. And until that work is undertaken with sincerity and courage, the question of whether Unity Day represents real unity or ritual will remain unanswered.

Simbarashe Namusi is a peace, leadership and governance scholar as well as media expert. He writes in his personal capacity.

Leave Comments