Audrey Galawu

“I remember the day my mother was arrested. The police officers came home asking for her. After they had taken my mother, we went to stay with my grandmother who lived close by us in Chitungwiza for the whole time my mother was behind bars.

“I never had an opportunity to talk to anyone about my mother’s incarceration,” says 16-year-old Faith, who is a daughter of an inmate at Jedidiah Trust’s Let’s Talk session where children of incarcerated parents open up about their experiences.

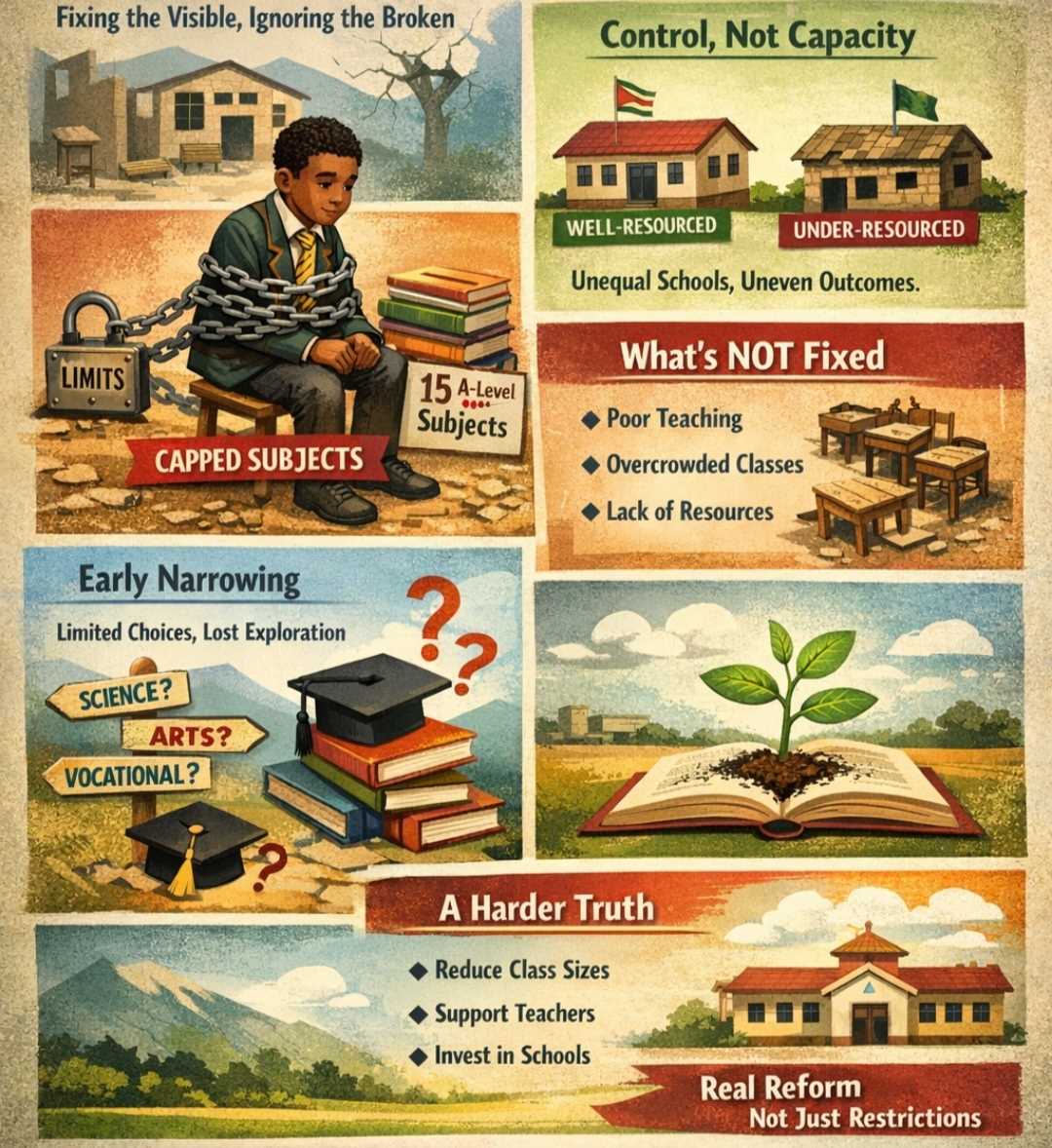

Having a parent incarcerated while you are still a child can be very traumatic. It can trigger disruptions that can result in poor performance in school or emotional distancing from friends and family.

Children whose parents are involved in the criminal justice system, in particular, face a host of challenges and difficulties: psychological strain, anti-social behaviour, suspension or expulsion from school, economic hardships, and criminal activity.

Faith says when her mother was arrested, she went on to live with her grandmother, a pensioner who automatically became their caregiver and breadwinner.

As children, they were not allowed to talk about their mother’s arrest as it was deemed an “adult” issue.

“It was a thing we weren’t allowed to talk about - it was seen as my mother’s personal business. I didn’t even receive support from school and I am not even sure if my school knew that my mother was in prison.

“All I know is that no one ever talked to me about it. It was a very tough time for me during that moment,” Faith added.

In all of this, children are the silent victims who bear the brunt more as they are not spared by the effects of the stigma attached to their mother.

Some of them might become the heads of the families, having to take care of younger siblings as the bread winners will be behind bars.

Follow-up services to help children process the trauma in a supportive environment are recommended for these children.

Jedidah Trust founder, Lovemore Chikwanda said the stigma suffered by children of incarcerated parents makes it difficult for them to live healthy lives.

“In Zimbabwe, there is need for policies that push the conversation to seal or expunge records of the formerly incarcerated. This push is meant to create a process that happens automatically for those that are eligible.

Related Stories

“By not having something like this, many formerly incarcerated people are left with a life sentence of perpetual punishment, through which they are blocked from employment and other opportunities that can support a successful re-entry.

“This can have a long-lasting impact on families, especially children. The inability to find work, the inability to take care of your family. Many young people take on that pressure, fearing that their parents may resort back to the thing that got them locked up in the first place.

“And oftentimes that is the case. Parents recidivate, leaving their children again. Children become depressed, feel abandoned, struggle and act out in school,” he said.

Compared to their peers, children with incarcerated parents often experience more adversity, such as dissolution of marriages or relationships between parents, parents’ substance abuse, extreme poverty, residential instability, and homelessness (Wakefield & Wildeman, 2013), making it important to consider factors that differentiate families prior to incarceration.

Prison rights activist, Lydie Mungala said children should have frequent interaction with the incarcerated parent six months or 12 months prior to the release.

“This will assist in breaking isolation, shame and fear from both parties.

“Provide age-appropriate information in a way that is appropriate for their age and developmental level. This will help children reduce anxiety and promote a sense of preparedness.

“Address emotional needs when a parent has spent several years in prison, the child gradually disconnects with the parent such that they have little or nothing to share with the incarcerated parent,” Mungala said.

Constitution of Zimbabwe

Sections 19 and 81 of the Constitution provide key provisions that relate to the rights of every child in Zimbabwe, including children accompanying their mothers in prison. Section 58 of the Prisons Act (Chapter 7:11) clearly specifies that, infant children may accompany their mothers in prison for a certain period of time, upon which when the child turns two years, he/she is removed to stay with relatives or an institutional home.

It is estimated that as at December 2017, more than 50 children were accompanying their mothers into Zimbabwe’s prisons across the country after more than 60 children were released together with their mothers under a Presidential Amnesty in 2014.

The majority of the children were less than two years old.

Jedidah Trust is an organisation that supports children with incarcerated mothers. Currently, the organisation is taking care of about 30 children.

Leave Comments