When government announces a new tax, the most important question is never what the law says. It is what people will actually do.

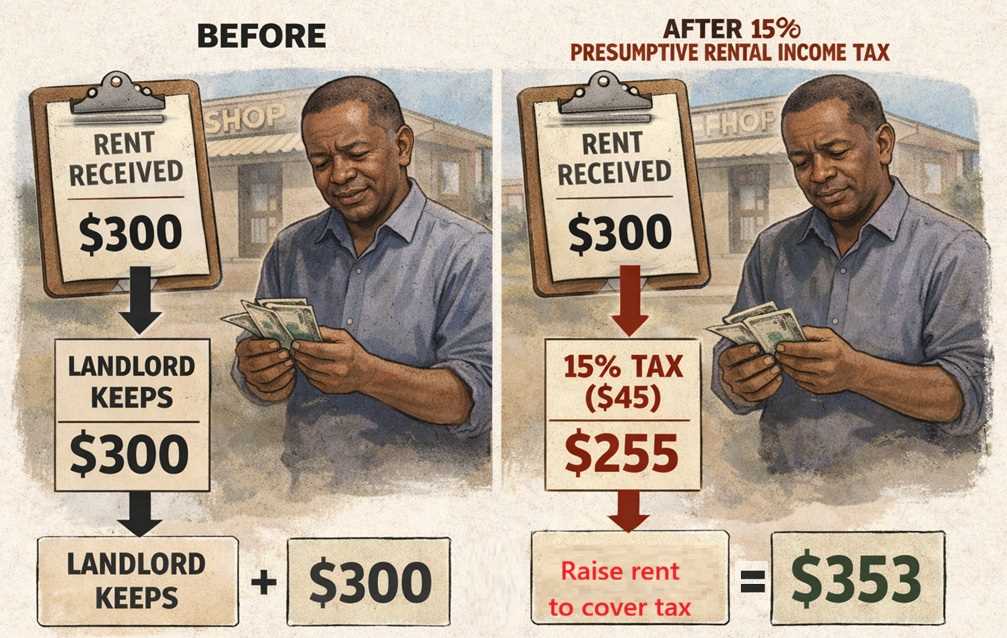

Zimbabwe’s new Presumptive Rental Income Tax, effective 1 January 2026, imposes a 15 percent tax on gross commercial rentals, payable by landlords and treated as a final tax, with no deductions allowed. On paper, the tax looks simple but in practice, it will impact the property market in many ways that the law might not have predicted.

Will property owners absorb the tax, or will tenants end up paying?

Almost certainly, tenants will carry the cost.

A 15 percent tax on gross rent, without allowance for maintenance, vacancies, rates, insurance, or inflation erosion is a structural expense. There is only one place to recover it: the rent itself.

What this means is an almost immediate upwards review of rentals. New leases will factor it in from the start. Renewals will come with “adjustments”, service charges, or management fees that achieve the same result without explicitly naming the tax. In real terms, this is a pass-through tax that lands on businesses already struggling with thin margins.

What does this mean for the cost of doing business and the formalisation drive?

Many commercial tenants already face municipal levies, licences, and a myriad of other compliance costs. Adding a further layer tied directly to occupancy increases pressure at the most fragile point of the business ecosystem: premises. Therefore, prices will be adjusted accordingly, meaning inflation.

Then the contradiction is hard to ignore. Government rhetoric speaks of reducing the cost of doing business and promoting formalisation, yet this tax increases fixed operating costs for SMEs, salons, workshops, traders, and start-ups.

The likely response to yet another tax is not likely improved compliance, but migration to cheaper, less regulated spaces that sit outside the tax net. With the advent of ecommerce, many small operators will likely choose to operate without physical business addresses.

Will landlords and tenants declare the real rental amounts?

Experience suggests many will not.

Because the tax is charged on gross rental income and allows no deductions, it creates a strong incentive to under-declare. Dual agreements, one for ZIMRA and another reflecting the true rental value, are a familiar coping mechanism in high-pressure tax environments.

Where the official rent is lower and the balance is settled privately, the letter of the law will be satisfied in a way that allows businesses to breathe. The tax assumes transparency, but the economic reality rewards discretion.

Does this turn tenants into tax enforcers?

In effect, yes.

The law allows ZIMRA to appoint tenants as statutory agents where landlords or intermediaries fail to remit the tax. In such cases, tenants may be directed to pay tax directly to ZIMRA out of future rentals, with temporary protection from eviction or rent increases linked to compliance.

While this protection sounds tenant-friendly, it fundamentally alters commercial relationships. Business tenants are placed in the uncomfortable position of policing their landlords’ tax affairs, a role that risks souring leases, escalating disputes, and creating long-term instability in commercial property arrangements.

Are estate agents and intermediaries a new risk point?

Related Stories

Very much so.

Estate agents and other intermediaries are required to verify that presumptive rental income tax has been paid before disbursing rental proceeds. They are also deemed statutory agents, meaning liability can shift to them if tax is not remitted.

In theory, this strengthens compliance. In practice, it creates space for abuse, especially in a market where many estate agents are already implicated in fraud. Agents may deduct tax without remitting it. Landlords may assume compliance based on assurances rather than proof. Tenants may discover months later that tax was never paid despite deductions being made.

Without transparent, accessible verification systems, the system leans heavily on trust in intermediaries, a risky design choice in a cash-constrained environment.

Who ultimately benefits from this tax design?

Presumptive taxes are attractive to revenue authorities because they simplify administration and reduce enforcement costs. A flat rate applied broadly delivers steady inflows. However, that simplicity comes at the expense of nuance.

The tax does not account for location differences, vacancy risks, maintenance burdens, or economic cycles. A struggling township shop and a premium CBD office face the same gross-based levy. In prioritising administrative ease, the policy sacrifices sensitivity to economic reality.

Tax forces thriving informal and quasi formal SME players to contribute to the fiscus

While the pressure of the tax on the economy will be felt, there is, however, a broader public-interest argument that cannot be ignored. Zimbabwe’s informal and quasi-informal economy has expanded rapidly, generating income, wealth, and rental demand while largely remaining outside the tax net.

Yet many of the same economic actors rely daily on publicly funded systems, from access to ARVs and public healthcare, to national identity documents, policing, roads, and municipal services. A tax system that consistently spares whole segments of economic activity while burdening a shrinking compliant base is neither sustainable nor equitable.

By extending taxation to commercial rentals linked to business activity, the presumptive rental income tax does, at least in principle, widen the net and reduce free-riding. The policy challenge is how to tax in a way that formalises economic activity without suffocating it, and builds compliance through fairness rather than fear.

What should Zimbabweans watch next?

Three trends will determine whether this tax stabilises or destabilises the market.

First, rising commercial rents as landlords reprice the tax. Second, the growth of shadow arrangements and under-declaration. Third, an increase in disputes involving agents, landlords, and tenants as liability lines blur.

If these patterns deepen, the tax may deliver short-term revenue while undermining trust, compliance, and business viability.

The bottom line

Whether the Presumptive Rental Income Tax becomes a sustainable revenue tool or another driver of informality will depend less on statutory wording and more on how much pressure the economy can realistically absorb before it adapts around the law.

And history suggests that when pressure mounts, Zimbabweans always find a way to adjust and cope.

Leave Comments