Munyaradzi Mashiri—Court Correspondent

Last week, a Zimbabwean court jailed Tanaka Gunda for 20 years for raping his 17-year-old maid, the judge citing “overwhelming evidence,” including a medical affidavit.

This case blows the lid off a hush-hush practice: hiring teenage girls into private homes—out of sight, out of protection—where power imbalances can turn deadly.

Why teens end up in kitchens—not classrooms

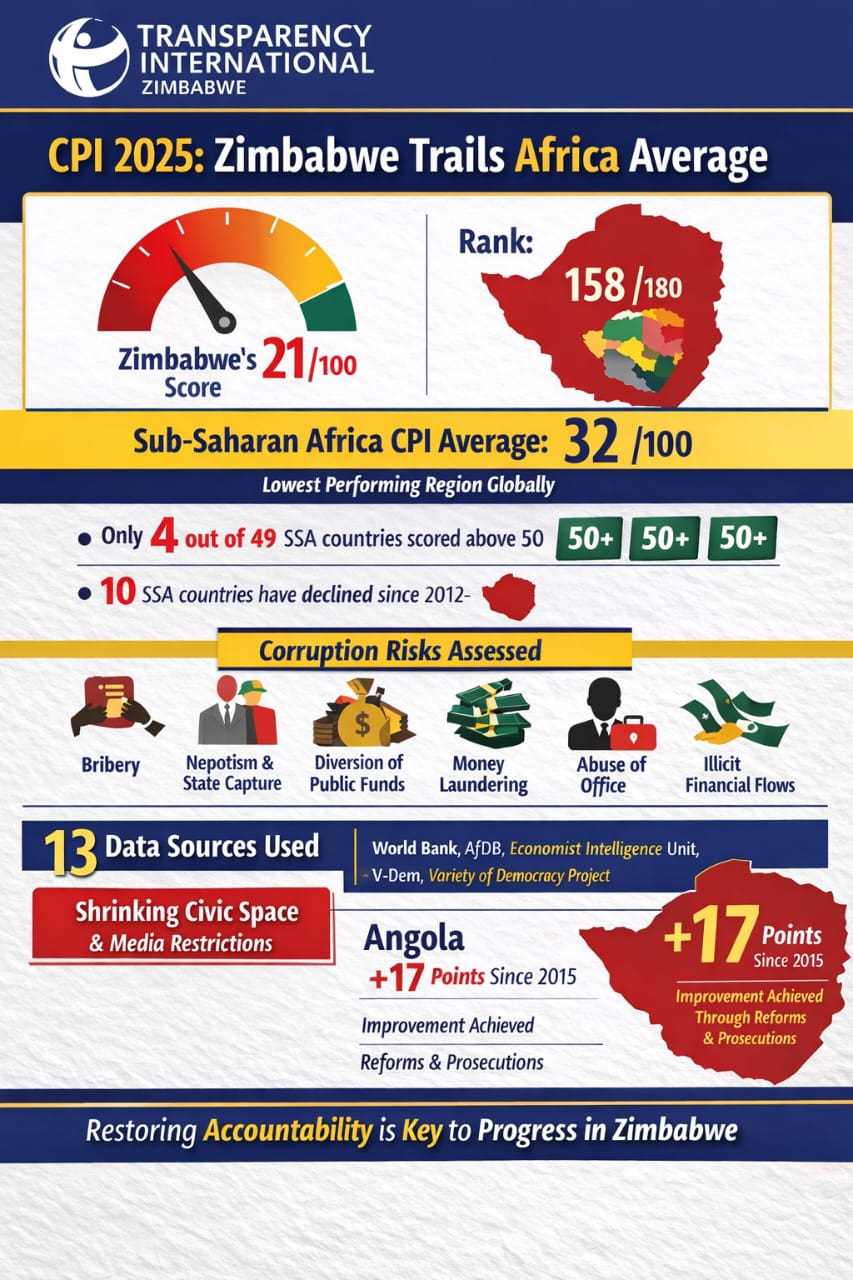

But the situation on the ground leaves many young girls as domestic laborers. A 2022 analysis of Zimbabwe data revealed that 1.5% of children are hidden child domestic workers, mostly girls, who often live away from biological families and face elevated

In Zimbabwe’s 2007 tally, orphanhood affected up to 24% of children under 18. Orphans were significantly less likely to attend school and more likely to be engaged in labor—especially when not closely related to the household head.

UNICEF warns of a stubborn education crisis, saying 47% of adolescents are out of school in Zimbabwe, with poverty, pregnancy, and abuse pushing many girls out by Form 4.

Historically, Zimbabwe has had one of the world’s highest orphan burdens (UNICEF once estimated about a quarter of children were orphans), a pipeline to child domestic work as teens scramble to buy food and keep siblings in school.

Some teen maids go into service to escape untenable home situations, such as abusive stepparents and poverty. Some of them also become breadwinners for their families, even paying school fees for siblings.

According to the 2023–24 Zimbabwe Health Survey, the national teenage pregnancy rate stands at 23%, up from 21.06% in 2015. With scarce social security nets, these teen mothers have to become earners, and domestic work is the most viable option.

Related Stories

Why do some people prefer teen domestic workers?

Some women told ZNyaya that they prefer to employ teenagers, as they are “more energetic” and easier to control. Others whisper about the real fear—older women might catch the wandering eye of the husband. So, the twisted logic goes, bring in a child.

“Men are attracted to women close to their age, so the thinking is: reduce the competition,” said Sympathy Taruvinga, 38. The Gunda case shows this is a poorly thought-out perception, as teens are more vulnerable to abuse.

Her friend Kimberly Chimwe, 30, said the cultural barriers to being tough on an older person and also the fear of physical altercations make teens more desirable as domestic workers: “It’s also about power. A teenage maid won’t talk back. She’ll obey. And if you shout at her, it doesn’t feel awkward.”

Another woman who refused to be identified said generally teens do not bring baggage, unlike older women. “The older women will always have some story—my child is sick, so-and-so has died and I have to go to the funeral, or they get back with their husbands and leave you stranded with no notice,” she said.

Another woman said teen maids are sometimes employed as a charity move. “When you go to the rural areas, the parents will come and plead for you to employ their daughter because of poverty. So you end up taking her to help them out,” she said.

Abuse behind closed doors

Because domestic work happens in private homes, abuse often goes unseen. In South Africa, a recent report noted 22% of surveyed domestic workers experienced verbal or physical abuse at work, and over a quarter felt unsafe—an indicator of the risk in the sector region-wide.

Social platforms regularly reveal allegations—voice notes, reels, and posts—about young maids being exploited. Examples include viral Zim posts alleging sexual abuse of a maid and short clips making similar claims. While most of these allegations do not end up in court and are unverified, it is undeniable that they add details to the disturbing picture.

The law is clear

Whatever the motivation, employing a minor is a legal landmine. The Labour Act is clear: employing anyone under 16 is prohibited. For those under 18, the law bans any work that endangers their health, safety, or morals. Offenders face fines, jail time of up to two years, or both.

Regionally, the SADC Protocol on Gender and Development orders states to “protect [children] from economic exploitation… and all forms of violence, including sexual abuse,” and to “develop concrete measures to prevent… teenage pregnancies… and child labor.” It also requires recognition and protection of domestic workers and “appropriate minimum remuneration.”

All images from UNICEF

Leave Comments