For years, 14-year-old Rufaro suffered in silence.

What began as intense pelvic pain during her menstrual cycle quickly spiraled into a harrowing ordeal that stretched from monthly discomfort to daily agony.

She bled so heavily that she often missed school and had to wear adult diapers—an experience no child should ever endure.

“It was the most painful experience to witness your child going through all that pain and you fail to help as a mother,” her mother recalls. “For Rufaro, it started when she was still a young girl in school, and it kept getting worse every day.

"We went to specialists, but it didn’t stop. We were given painkillers and that was all the help we could get at the time. I wish I could have done more to get her the help she needed.”

Despite her mother’s desperate search for answers, a proper diagnosis never came. Specialist care was far too expensive, and some people even told them that Rufaro’s pain was spiritual rather than medical.

Rufaro’s story is not unique. It echoes across rural and urban Zimbabwe, where girls and women silently battle the debilitating effects of endometriosis—often without access to diagnosis, treatment, or understanding.

Endometriosis in the Shadows

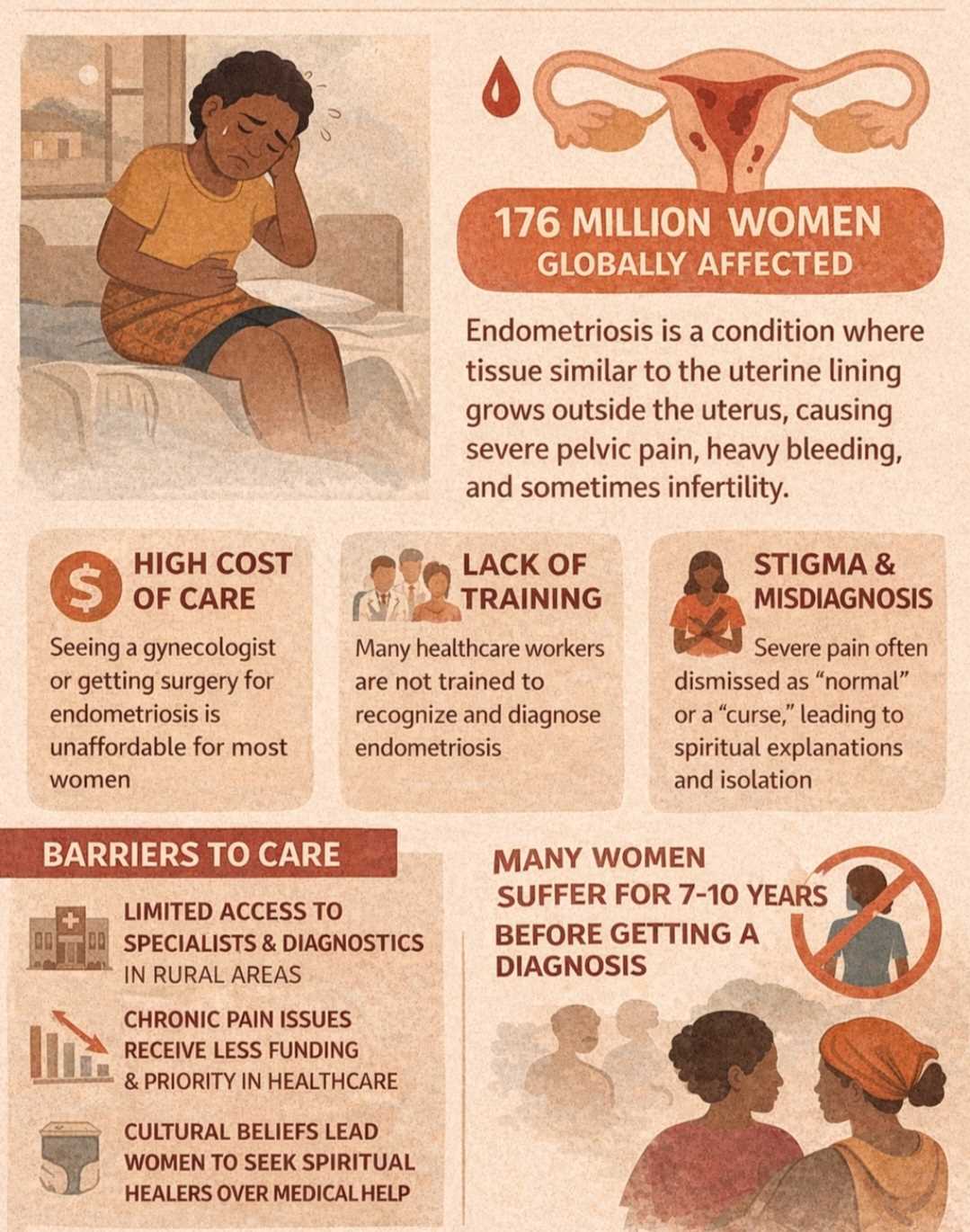

Endometriosis is a condition where tissue similar to the uterine lining grows outside the uterus, causing severe pain, heavy bleeding, and sometimes infertility. It affects an estimated 176 million women globally. Yet in Zimbabwe and many African nations, it remains in the shadows—misunderstood, misdiagnosed, and rarely spoken of.

“The biggest challenge is access to treatment and medical attention,” says Tinevimbo Matambanadzo, founder of the Zimbabwe Endometriosis Support Network.

“We’ve seen a lot of growth in menstrual health education around period poverty, but endometriosis awareness still lags far behind. Women are still being told their pain is ‘normal’ or spiritual. Some are even told that pregnancy will ‘cure’ them, which is a dangerous myth.”

She adds, “Just seeing a gynaecologist is expensive. An operation for endometriosis? That’s around US$5,000. Most can’t afford that. Some women have to use adult diapers because of how much they bleed—and those are expensive too.”

The lack of awareness is pervasive—not just among the public but also within the healthcare system. Many women spend years without a diagnosis. In rural areas, cultural stigma adds another barrier. Painful menstruation is often dismissed as jeko regono—a burden of womanhood that must be quietly endured. Others are told their pain is a curse, punishment, or spiritual affliction. These beliefs lead women away from medical care and into isolation.

Medical Bias and Cultural Stigma

Much of the global medical literature has historically claimed that endometriosis is rare among Black women. This bias has had dangerous consequences. African women often experience longer diagnostic delays and poorer outcomes.

A recent commentary on menstrual disorders in African countries found that there was “limited data and silence” on vaginal bleeding outside menstruation—bleeding that could signal serious conditions like fibroids, post-partum complications, or endometriosis.

The same report called for urgent improvements in educating healthcare workers and menstruating women on what constitutes normal and abnormal bleeding. When menstruation is shrouded in shame, symptoms like Rufaro’s are ignored until it’s too late.

“There are deeply ingrained cultural beliefs and a pervasive stigma around menstruation and menstrual pain,” says Tawanda Njerere, Chief Operations Officer at ZimSmart Villages. “Menstruation itself is often considered a taboo subject. This silence extends to menstrual pain, which is frequently dismissed as a normal, unavoidable part of being a woman. That normalization causes women to endure pain rather than seek medical help.”

Some communities even view menstrual pain as a curse or result of witchcraft. This drives women to traditional healers or leaves them feeling ashamed and isolated, delaying much-needed medical care.

Why Endometriosis Is Still Not a Public Health Priority

“From our perspective at ZimSmart Villages, there are several layers to why endometriosis remains largely unspoken in public health spaces, especially here in Zimbabwe,” says Njerere. “Firstly, there's the cultural conditioning that normalises menstrual pain. Many women don’t speak up, and when they do, their pain is dismissed.”

There’s also a significant lack of training among healthcare professionals, particularly at the primary care level in rural and peri-urban areas. Endometriosis is complex and without adequate training, it is often misdiagnosed or dismissed.

Additionally, public health priorities tend to focus on more measurable, life-threatening illnesses like malaria, HIV, or tuberculosis. Chronic pain and reproductive conditions, which don’t kill but erode quality of life, receive less attention and funding.

Related Stories

What Women with Endometriosis Need

“In our communities, women with endometriosis need multi-faceted support that addresses their physical, emotional, and social well-being,” explains Njerere.

Information and Early Diagnosis: Community health workers need training to identify red flags and refer suspected cases early. “Early diagnosis can prevent years of suffering and improve outcomes.”

Psychosocial Support: “Chronic pain and infertility can be isolating. Women need support groups or even informal community networks to share, vent, and connect.”

Affordable Treatment: With most surgeries out of financial reach, public clinics must be stocked with basic pain medications, and clear referral pathways for advanced care must be established.

Destigmatisation and Advocacy: “We need to create an environment where women feel safe discussing their symptoms,” says Njerere. “Only then can communities offer support and push for policy change.”

Empowering Local Clinics and Health Workers

ZimSmart Villages is also working to empower the frontline. “We believe targeted, practical training for healthcare workers, especially nurses and primary care providers, is crucial,” says Njerere.

Partnering with platforms like MyCpdZw, they are developing CPD modules that teach health workers to recognize and respond to symptoms of endometriosis.

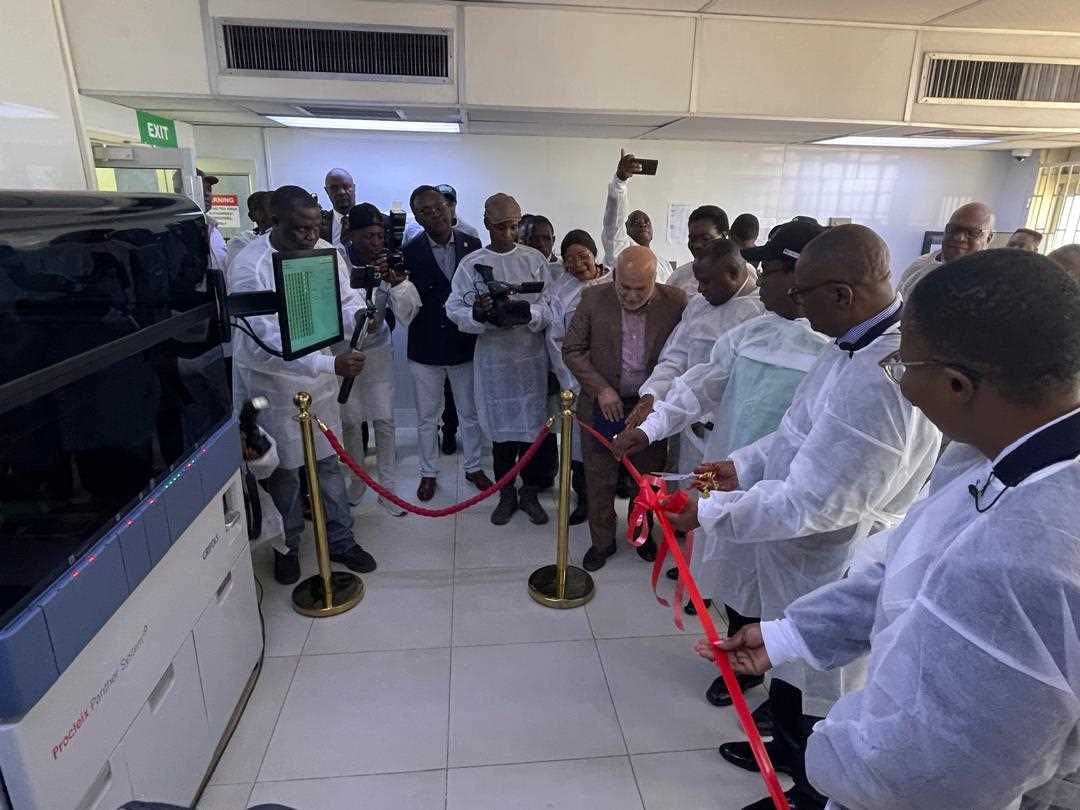

Technology is also playing a role. ZimSmart Villages uses telehealth platforms to connect rural clinics with specialists, helping guide diagnosis and management in real-time. “Our Telehealth Kiosks reduce the distance between a patient in a remote village and a trained gynaecologist.”

Policy Change: What’s Needed Now

ZimSmart Villages is advocating for a holistic policy shift to support women with endometriosis:

National Awareness Campaigns: Led by the Ministry of Health in collaboration with local organisations to promote awareness through radio, community events, and school health programmes.

Training and Guidelines: Mandatory integration of endometriosis into medical training and simplified diagnostic tools at clinic level.

Subsidised Treatment: Access to ultrasounds, pain medication, and surgical options must be made affordable through public health funding.

Specialised Referral Centres: Provincial hospitals should house dedicated endometriosis clinics for complex cases.

Research and Data Collection: More localized data is needed to inform funding, treatment protocols, and public education strategies.

ZimSmart Villages: Spotlighting the Unseen

At the heart of all this work is community-led innovation.

ZimSmart Villages trains local champions—trusted community health workers—to raise awareness about endometriosis. They’re also integrating endometriosis education into their nutrition and wellness programs, using culturally appropriate materials to break the silence.

“Through our Telehealth Kiosks, we’re enabling private, stigma-free consultations where women can finally voice symptoms they’ve been afraid to share,” says Njerere. “And through community engagement, we are slowly but surely changing the narrative.”

For Girls Like Rufaro, Silence is a Cost Too High

Rufaro’s mother says the years of unanswered questions and helplessness have left her with deep regret. “I keep thinking—what if we had found help sooner? Maybe she wouldn’t have suffered this long. As a mother, that thought never leaves you.”

For girls like Rufaro, the cost of silence is more than missed school days or chronic pain. It’s missed opportunities, eroded self-esteem, and years of unnecessary suffering.

Leave Comments