Zimbabwe’s elections no longer shock or surprise. The country votes, tension rises, disputes erupt, and institutions scramble into reactive mode. The surface details change every five years, but the underlying pattern has remained the same since 2008: mistrust, confusion, and institutional strain.

The core problem is not the voting. It’s the vacuum that opens immediately after.

Zimbabwe has no structured post-election conflict-management system. No national playbook for mediation, de-escalation, or coordinated communication. We have ZEC, the courts, Parliament, and dialogue platforms like POLAD, but they operate in isolation. They were never designed to fuse into an integrated electoral peace architecture.

This is why every contested election becomes improvisation.

When disputes arise, institutions respond in silos. Courts interpret the law, ZEC explains results, political actors negotiate under pressure, and the public is left decoding competing narratives. The Tshabangu recalls were an extreme illustration of how fluid and vulnerable the system is: legal, political, and administrative processes can reshape the electoral landscape long after ballots are cast. The institutions did not prevent the shock. They merely absorbed it.

Other African states confronted similar cycles and decided to break them.

Kenya built early-warning and mediation mechanisms after 2007.

Ghana entrenched inter-party dialogue platforms.

Malawi strengthened judicial transparency and public trust.

They built electoral peace architectures—systems that activate automatically when disputes threaten stability.

Zimbabwe has not built one.

Related Stories

Partly because no institution has the mandate, and partly because political incentives favor flexibility over predictability.

This absence will matter even more as we approach 2028.

The ruling party enters the next election balancing four internal centers of power: business-linked networks protecting accumulated interests, securocratic actors safeguarding continuity, technocrats driving the Vision 2030 narrative, and ambitious provincial blocs jostling for influence. These groups shape the political temperature long before any ballot is printed.

The opposition, still unsettled after the recalls and leadership ruptures, enters 2028 with structural fragility. In such an environment, even a routine dispute can trigger the familiar institutional scramble.

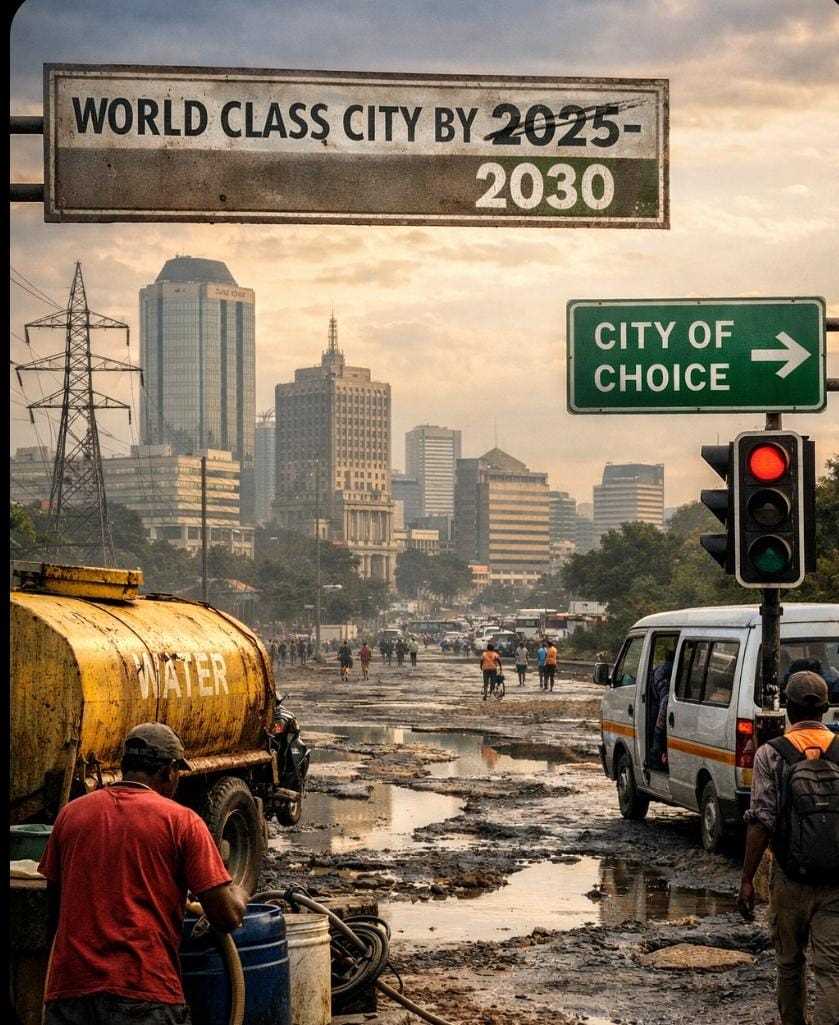

Vision 2030 will be the centerpiece of the continuity narrative. If economic stabilization and infrastructure momentum become visible, the ruling party will argue that stability and progress must not be disrupted. But legitimacy is multi-dimensional. It is measured not only in roads and reforms but also in the confidence citizens have in the electoral process, especially in the moments when results are contested.

Zimbabwe does not need another symbolic forum or one-off commission.

It needs a formal post-election conflict-resolution framework: a defined structure for mediation, institutional coordination, and transparent communication. A system that removes improvisation from moments of national pressure.

Zimbabweans are not exhausted by elections.

They are exhausted by the uncertainty that follows them.

The ballot box is not the problem. The silence and confusion after the ballot box closes is. That is something we can fix if we choose to design a system worthy of the democracy we claim to value.

Simbarashe Namusi is a peace, leadership, and governance scholar as well as a media expert. He writes in his personal capacity.

Leave Comments