Paul “Tempter” Tungwarara moves like an answer prepared in advance: Dubai flights, quick contracts, polite press statements, and projects that surface exactly where political credit is most useful. He looks like the polished face of a new entrepreneurial class. But his rise is less biography than blueprint: the clearest signal yet of how Zimbabwe is reconfiguring state power through private intermediaries.

Tungwarara did not inherit influence from the liberation ledger. He is a post-2000 operator: internationally mobile, politically fluent, and adept at turning foreign networks into domestic opportunities. Prevail International Group, his Dubai-facing vehicle. does construction, logistics, mining facilitation, and, increasingly, state-linked development. Add the formal paper title (Special Presidential Advisor on Investment (UAE) and the informal reality (presidential proximity), and the picture is of someone who can open doors that most cannot

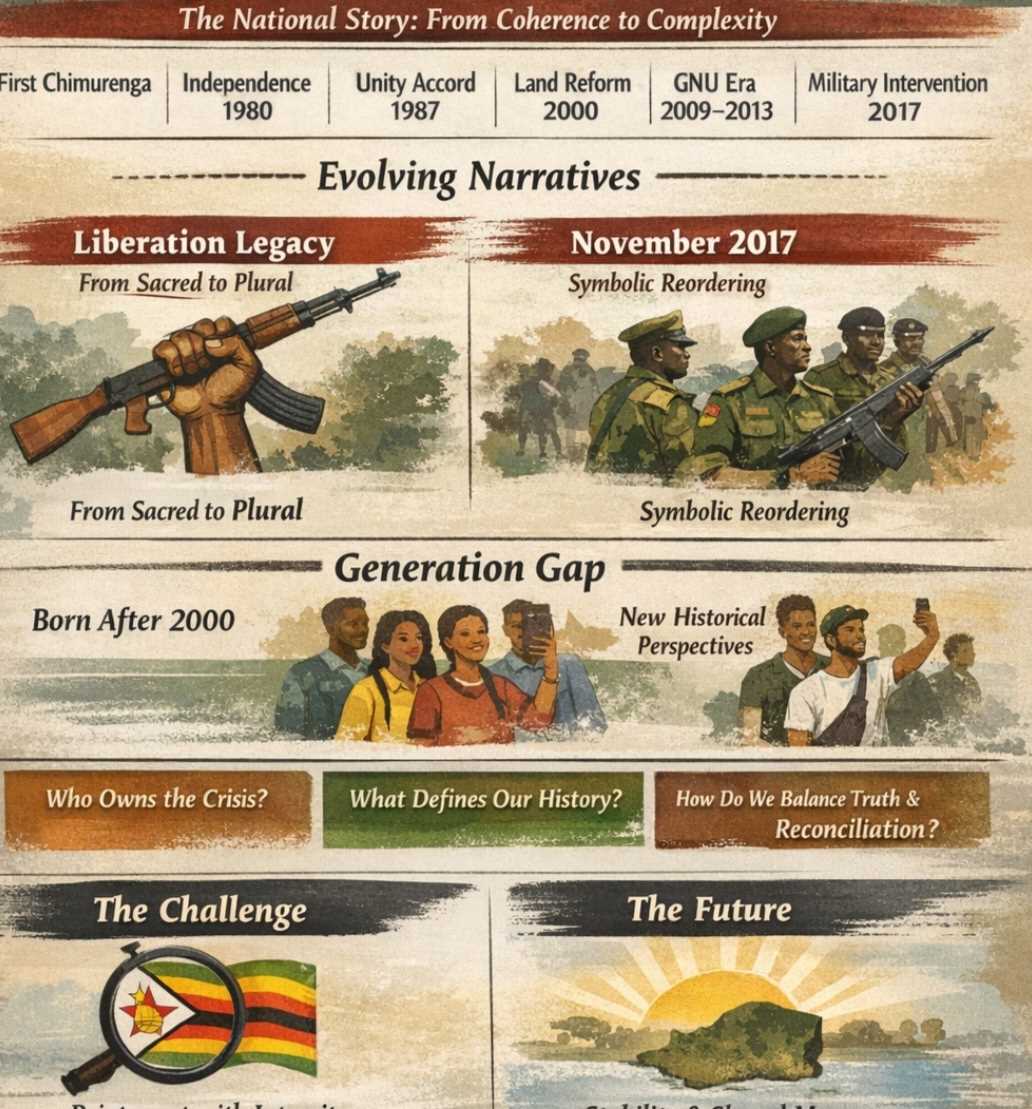

This is not a one-man story. It’s an institutional pivot. Zimbabwe’s patronage economy has historically recycled elites who could convert connections into resources: diamonds and fuel in the 2000s and contractor-state hybrids in the 2010s. The 2020s’ archetype looks different: globally connected, politically embedded, and useful in a diplomatic era defined by new partners. Tungwarara is the model for that shift.

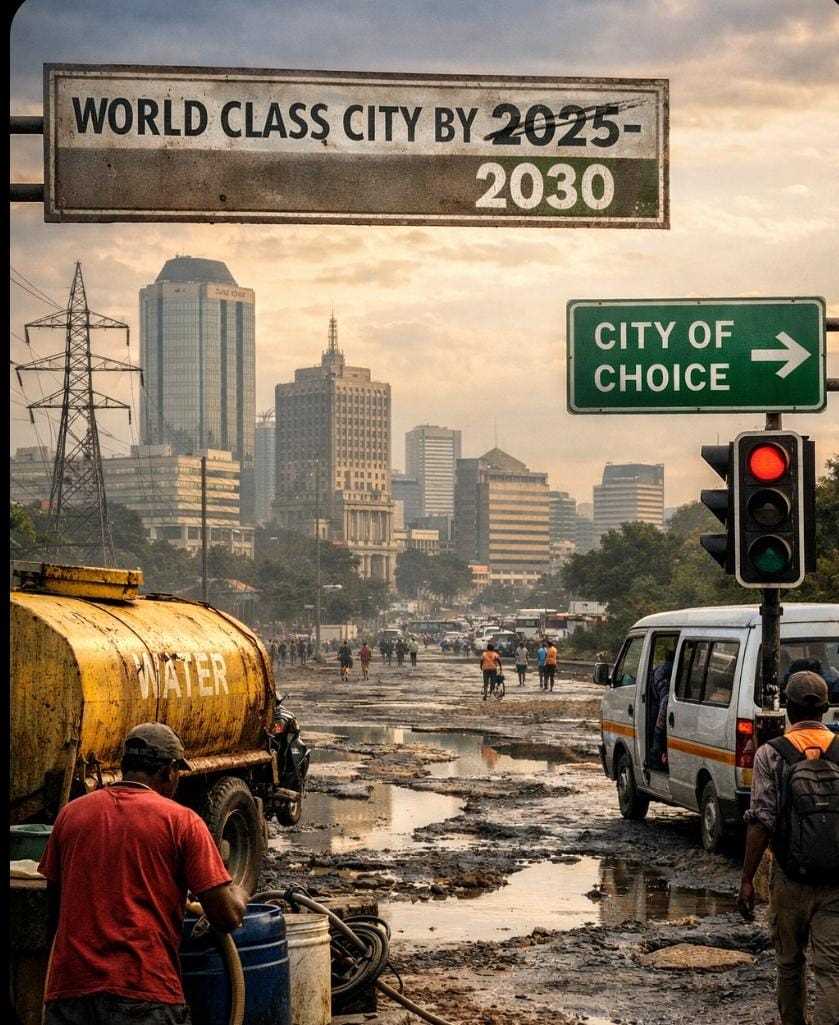

The projects tethered to his name matter because they matter politically. The Presidential Borehole Scheme and Village Business Units (VBUs) are potent symbols: visible, local, and easy to credit to a presidency projecting competence. On paper, these interventions are transformative: water, energy, and livelihoods.

On the ground, they expose the trade-offs of outsourcing public delivery to private, politically anchored actors. A 2023 Portfolio Committee review found that over 25% of newly drilled boreholes under the national program were malfunctioning or incomplete within months of commissioning. That statistic is not an attack; it’s an institutional alarm, evidence that speed and visibility have sometimes trumped durability and oversight.

Related Stories

Controversies follow. Public records show a US$2.3 million property dispute, a US$350,000 debt claim, and repeated parliamentary complaints about substandard or short-lived installations. Whether these cases stand or collapse, they shape a public narrative: influence can lubricate access, and access can blunt procedure.

But there is a counterpoint worth stating plainly: supporters insist Tungwarara executes at a tempo government departments struggle to match. In a polity where donors are cautious, Chinese credit is tightening, and Western engagement is conditional, the state faces a tactical problem: how to show results without rebuilding the entire institutional architecture. Private intermediaries like Tungwarara can, for all their flaws, deliver fast, visible outputs that the presidency needs for political traction.

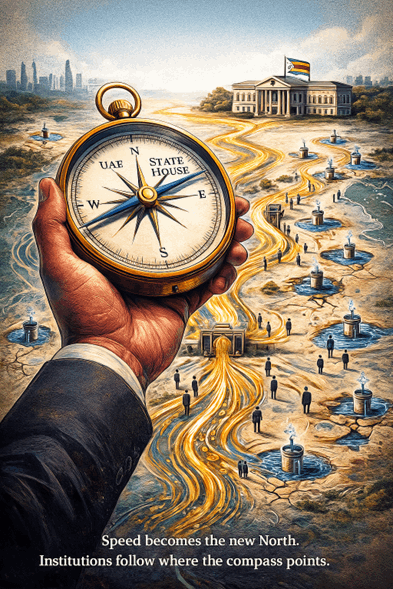

That is why his rise makes sense now. Zimbabwe requires capital, speed, and political control simultaneously. Traditional aid and concessional finance come with strings or delays; domestic institutions are often slow; the political calendar rewards visibility. The UAE offers capital plus political discretion. Tungwarara offers the bridge: presidential trust, UAE access, and the operational nimbleness ministries often lack. In short, he is not only a contractor—he is a mode of governance.

The endgame is less a ledger of profits and more a reconfiguration of power. Channel enough projects through politically trusted intermediaries and you centralize control, build a new cohort of loyal elites, and create curated gateways for foreign capital. Every borehole branded under the presidency is also a parcel of political capital. The resulting elite is not grounded in liberation credentials or industrial depth but in loyalty, access, and the ability to mediate international money flows.

That model has consequences. Development risk becomes entangled with patronage; public resources flow through loyalty pipelines rather than competitive, transparent processes; and institutional accountability lags behind the speed of delivery. The danger is not only capture for personal enrichment. It is the slow erosion of governance norms, where visibility substitutes for sustainability and where political optics become the primary metric of state performance.

Tungwarara is not the architect of this transformation; it is just its most visible expression. Watching his ascent is less about one man’s morality than about watching a system repattern itself. If the state continues to prefer rapid, political wins mediated by trusted intermediaries, Zimbabwe may see faster, messier development, some real gains, many governance costs, and an elite whose power depends more on proximity than on competence.

That is the calculation in play now. The question for Zimbabwe in next decade is whether it can capture the benefits of speed without surrendering the institutions that make speed sustainable. Until then, men like Tungwarara will be both the engine and the symptom of a new political economy.

Simbarashe Namusi is a peace, leadership, and governance scholar as well as a media expert. He writes in his personal capacity.

Leave Comments