In Chiweshe, Mashonaland Central, a 52-year-old farmer watches the clouds thicken with both hope and dread. The rains promise a good maize crop, yet they also signal the return of malaria season.

“Last year I spent more time lying down than in the fields,” Mai Mukweva says. A lingering malaria bout left her too weak to tend crops, and the harvest was not as good as it should have been.

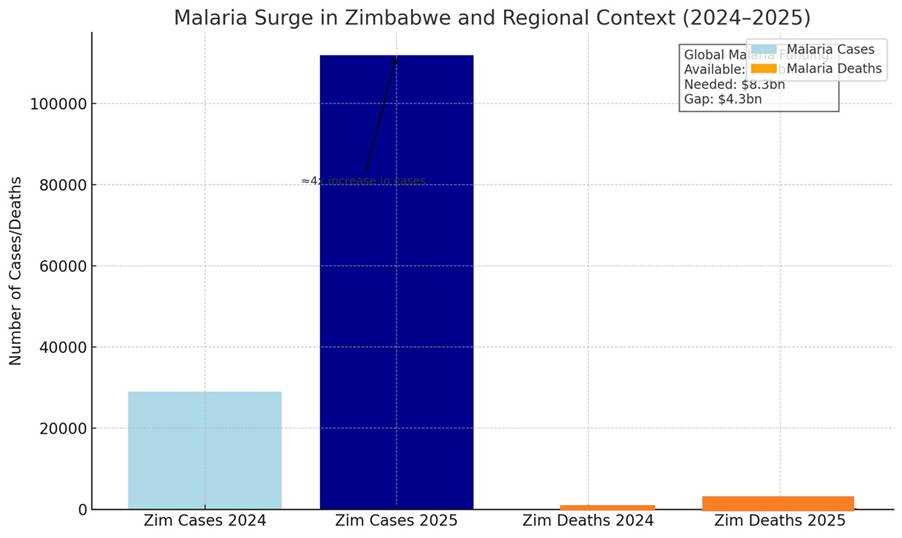

Her fears echo a national crisis. Zimbabwe has seen a sharp malaria rebound in 2025, recording about 112,000 suspected cases and more than 300 deaths by mid-year. The same period in 2024 registered only 29,000 cases and 49 deaths.

Provinces such as Mashonaland Central, Mashonaland East and Manicaland are carrying the heaviest burden, leaving rural clinics under pressure and farmers like Mai Mukweva vulnerable.

Related Stories

The pattern is not unique to Zimbabwe. Across southern Africa, malaria cases are rising again. Botswana, Namibia and Eswatini have all reported new outbreaks, fuelled by erratic rains, warmer weather, and gaps in spraying and surveillance. The Southern African Development Community (SADC) has policies in place — including the Elimination 8 (E8) initiative to coordinate cross-border spraying and surveillance — but translating these into consistent field action remains a challenge.

Mai Mukweva says that in years gone past, spraying to kill mosquitos was consistent, with health workers distributing treated nets regularly. “Now we see them here and there. It’s not the same,” she says.

She is talking about the health funding shortfalls affecting many countries. According to the World Health Organization, $8.3 billion is required annually for global malaria control, yet only $4 billion was available in 2023. That $4.3 billion gap trickles down to SADC in the form of delayed insecticide-treated net distributions, broken supply chains for drugs, and stretched rural health staff.

Still, communities are not helpless. Mai Mukweva said health workers have educated them to clear stagnant water, cut back grass, and seek treatment at the first sign of fever.

She said preventive tools are also more accessible: mosquito nets now sell for around $5, a price many families can manage even without donor support.

Yet local solutions can only go so far without sustained investment and stronger coordination. For families like Mai Mukweva’s every malaria outbreak means lost harvests, missed school days, and drained incomes.

Leave Comments