By Solo Musaigwa

When President Emmerson Mnangagwa hints at extending his presidency from 2028 to 2030, the move appears, at first glance, modest. Just two extra years in office. Yet, in the political psychology of post-liberation Africa, such an extension carries the weight of history. Zimbabwe’s story, like that of many liberation movements turned ruling parties, reminds us that revolutions rarely know when to end. The problem is not that Mnangagwa wants to “finish what he started,” but that in the name of finishing, the spirit of renewal is extinguished under the nostalgia of victory.

Zimbabwe’s liberation war, the Second Chimurenga, was more than a military campaign. It was a moral covenant. The young men and women of ZANLA and ZIPRA fought not merely for power, but for a just, equal, and self-governing nation. That moral authority propelled ZANU-PF to power in 1980 and cemented its status as the vanguard of freedom. Yet, as with most liberation movements, moral legitimacy slowly hardened into political entitlement. The belief that “the party and the people are one” evolved into the assumption that the party alone knows what is best for the people. Over time, liberation ideals gave way to control first over politics, then over the economy, and eventually over the truth itself.

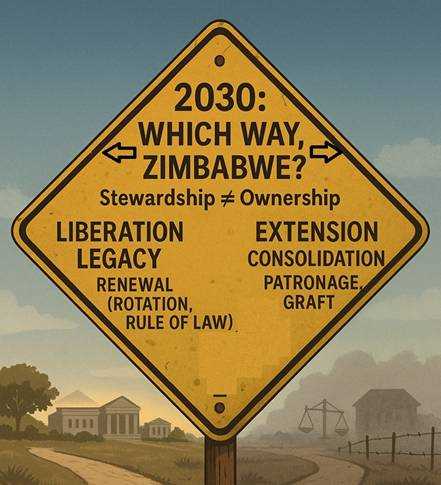

Mnangagwa’s 2030 ambition sits squarely within that tradition. His government justifies it as continuity. Continuity of policy, stability, and economic vision. But the distinction between continuity and consolidation is thin. When a leader extends his stay, institutions contract. The rule of law bends subtly to accommodate the ruler’s ambitions. Civil servants, judges, and business elites begin to orient themselves toward loyalty, not merit. What begins as a small constitutional amendment often ends as a large moral decline.

This is where corruption thrives. Power extended is power unaccountable. In a nation already bruised by graft, tender manipulation, and political patronage, prolonging a presidency risks normalising what has long been lamented. Zimbabwe’s corruption is not random. It is systemic. It flows from the very structure of prolonged incumbency where political survival depends on rewarding networks of loyalty. An extended presidency will only deepen this ecosystem of favouritism, transforming Vision 2030 from a national development plan into a patronage mechanism that keeps elites comfortable while citizens remain restless.

Consider what happens when power stops fearing rotation. State contracts are awarded not to the most capable but to the most connected. Public funds become instruments of political gratitude. Oversight bodies such as anti-corruption commissions, audit offices, parliamentary committees become theatre, not tribunals. The liberation generation once fought against a system that denied them control over their own destiny. Ironically, their successors now reproduce the same logic: centralised control masked as patriotic duty.

Related Stories

History offers sobering parallels. Angola’s José Eduardo dos Santos ruled for nearly four decades under the banner of post-war reconstruction. What began as a promise of stability became an edifice of systemic corruption, where oil wealth enriched the few and drained the many. Mozambique’s FRELIMO followed a similar path, transforming the rhetoric of liberation into a network of oligarchic privilege. Zimbabwe now stands on that same precipice.

Botswana and Ghana, by contrast, show what rotation does. It interrupts corruption’s rhythm. Leadership change even within the same party injects accountability and redefines loyalty. Institutions outlive personalities. The nation becomes larger than the leader. Mnangagwa’s 2030 ambition risks freezing Zimbabwe’s political life, ensuring that loyalty to one man remains the passport to prosperity.

There is a deeper philosophical problem at play. The philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche once observed that “the state is the coldest of all monsters.” It claims to act in the people’s name while devouring their freedom bit by bit. In liberation regimes, this happens quietly not through open tyranny, but through the moral certainty that “we alone liberated the nation; therefore, we alone must guard it.” Such thinking confuses stewardship with ownership. The nation becomes a private estate, guarded by liberation credentials instead of democratic consent.

Zimbabwe’s youth see through this illusion. They are the generation born after the struggle yet living through its consequences. They have watched the liberation narrative mutate into a justification for greed, repression, and silence. For them, Vision 2030 rings hollow if it means two more years of the same old politics of contracts traded in backrooms, of loyalty rewarded over skill, of progress measured by who benefits from proximity to power rather than who contributes to national growth.

If Mnangagwa truly wants to be remembered as a reformer, the answer is not to extend his rule but to institutionalise it. A genuine legacy lies in creating systems that outlast their architects in ensuring that the fight against corruption is not a campaign but a culture. The greatest act of leadership would be to strengthen the constitution, not bend it; to build trust, not fear; to show that liberation was not a lifetime licence to rule but a mandate to serve.

As Zimbabwe edges toward 2030, it faces a fundamental question. Will it continue to be a nation led by its past, or one reborn through accountability and renewal? Extending the presidency may deliver short-term control, but it will deepen the rot of corruption that already corrodes the state’s moral core.

True liberation is not in clinging to power, but in releasing it responsibly. Mnangagwa’s generation freed Zimbabwe from foreign rule. Now it must free it from internal decay. If that freedom does not come, 2030 will not mark Zimbabwe’s rise. It will mark the moment liberation devoured its own promise.

Solo Musaigwa is a Zimbabwean writer, political commentator, and social critic whose work blends history, prophecy, and people’s voices into sharp indictments of power. He writes from within the traditions of the liberation struggle, amplifying the voices of mothers, widows, youth, exiles, and ancestors who demand bread, dignity, and freedom.You can contact him at solomusaigwa.writer@gmail.com

Leave Comments