“We May Be Small, But Our Dreams Are Big”: Life with Turner Syndrome in Zimbabwe

At first glance, Vimbainashe Hove of Gweru could pass for a teenager. She is 24, and determined, but her small frame often invites stares and assumptions.

“People think I’m a child because of my height,” she says. “But I’m an adult — I want to be seen that way.”

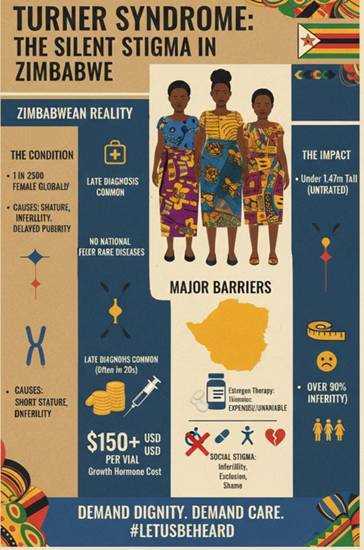

Vimbainashe lives with Turner Syndrome, a rare genetic condition caused by missing or structurally altered X chromosomes. It affects about one in every 2 500 female births worldwide and results in short stature, infertility, and delayed or absent puberty. For women like her, the journey into womanhood is shaped by bodies that don’t grow or mature as society expects — a reality that brings both visible and invisible pain.

“Sometimes you feel like you’re not a ‘real woman’,” she adds. “People ask why you don’t have children or laugh at your size. It hurts.”

Related Stories

Vimbainashe says rejection in relationships and exclusion from social spaces make the struggle heavier than the medical condition itself. “It’s rare to find a man who is attracted to you. Sometimes you can go months without anyone even asking you out.”

In Zimbabwe, access to diagnosis and treatment for Turner Syndrome and Growth Hormone Deficiency — another disorder that delays growth and hormonal development — remains limited. Many girls reach adulthood without ever knowing what is wrong.

Dr Margaret Makata, a gynaecologist in Zvishavane, says most patients arrive too late for effective intervention.

“When a young woman comes to the clinic at 20 years old without having developed breasts or started menstruation, it is already too late for some of the medical treatments,” she explains. “Families often don’t understand what is happening, so these girls live for years in confusion and shame before they get help.”

Treatment costs also lock many out. “Growth hormone injections can cost over US $150 per vial, while oestrogen therapy is expensive and rarely available in public facilities,” Dr Makata says. “Without treatment, these women face lifelong complications such as heart defects, weak bones, and delayed puberty.”

Globally, over 90 percent of women with Turner Syndrome are infertile, and without early diagnosis, most remain under 1.47 metres tall. Yet Zimbabwe has no national registry for rare diseases — leaving many undiagnosed, untreated, and unheard.

Dr Makata believes that must change. “We need awareness campaigns, early screening, and access to affordable hormone therapy. These women deserve dignity and care, not stigma and silence.”

For Vimbainashe, dignity means being accepted as she is.

“We may be small in size,” she says with a smile, “but our hearts and dreams are just as big as everyone else’s.”

Leave Comments