By Memory Kadau

The African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) has been touted as a revolutionary agreement on the cusp of redefining the continent’s economic destiny. But to the millions of women hawking tomatoes near the border post at Mutare or knitted garments on the streets of Mbare, the revolutionising possibilities of free trade exist afar. Why? Because, despite the talk of inclusion, the everyday experience of women living in the informal economy remains on the periphery of trade policymaking.

If AfCFTA is to be effective, it needs to put the women holding Africa’s informal markets at the forefront.

In Zimbabwe, over 80% of employment lies in the informal sector, and women are the majority within it. They are cross-border traders, small-scale farmers, market vendors, and street entrepreneurs. Their economic resilience is unmatched. And yet, national policies and trade negotiations continue to treat them as invisible or, worse, criminal. This structural exclusion not only undermines Zimbabwe’s economic potential but also reveals the limits of current Feminist Foreign Policy (FFP) frameworks when they are not grounded in decolonial and context-specific approaches.

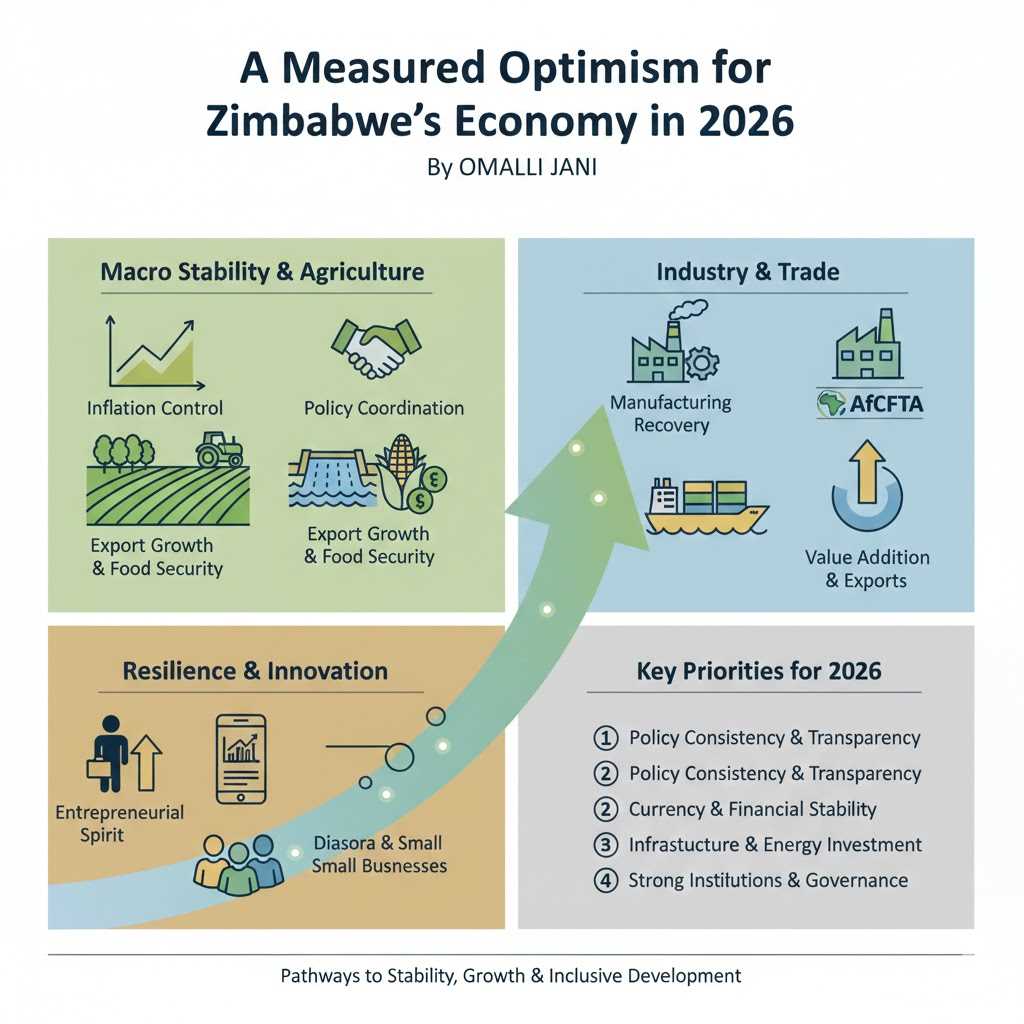

My recent study, spanning Angola, Tanzania, South Africa, and Zimbabwe, shows that the AfCFTA – despite its ambitions – currently serves formal sectors and elite actors far more than it does grassroots women. While AfCFTA documents pay lip service to gender inclusion, implementation on the ground remains bureaucratic and technocratic, with little room for informal traders to shape or even understand these processes. In Zimbabwe, women’s economic participation continues to be policed rather than supported. Our cross-border traders endure corruption, sexual harassment, and arbitrary taxation, all while being hailed as the ‘backbone of the economy.’

Zimbabwe's gender policies, including the National Gender Policy and Zimbabwe Gender Commission Act, promise the world on paper. But absent concerted action to bring the viewpoints of the informal sector into economic and trade discussions, even these policies run the risk of becoming mere promises. A Feminist Foreign Policy worthy of the term needs to reach from formal workplaces and boardrooms into the roadside stalls, market pavilions, and vendor buses, which are throbbing with economic vitality.

Decolonial FFP resists the Western assumption that feminist politics is solely about boardroom representation and fair remuneration. Gender justice in Zimbabwe and most Majority World countries entails access to land, safe borders, cheap credit, and relief from everyday structural violence. It entails the validation that unpaid care work, which is commonly women's work, constitutes an indispensable economic contribution that needs policy intervention. It entails the restructuring of trade policies in a manner that the informal economy is neither taxed nor exploited but invested back into—by way of health care, sanitation, training, and affordable infrastructure.

Related Stories

Then what should we do?

First, regional economic policies and negotiations on trade need to be fundamentally opened up. Negotiations with local women’s organisations on the ground—such as those active at Beitbridge and Forbes border posts—should be institutionalised, rather than symbolic. They should be heard, more importantly, heeded. Secondly, gender-responsive budgeting needs to allocate specific funds to assist women in the informal sector, particularly on cross-border movement, IT literacy, and affordable credit. Thirdly, our tax reforms need to be rethought: the ongoing push towards the formalisation of the informal economy needs to move less towards extraction and more towards empowerment.

But we cannot do this alone. Philanthropic actors and international partners must fund, not just audit, feminist movements. We need long-term flexible funding, not short-term donor fads. Institutions like Mama Cash are leading the way by resourcing grassroots feminists to reform trade policy from below. We need more such allies.

Regional bodies like SADC and the African Union must also harmonise gender-responsive trade frameworks. At present, fragmented mandates and poor coordination mean that women fall through the policy cracks. Zimbabwe, as a key player in both SADC and the AfCFTA, must lead the charge in championing gender-just trade from the grassroots up.

Finally, Zimbabwean women must continue to organise. From market stalls to parliaments, our voices must not be silenced. Our experiences are not marginal; they are central to building a trade policy that works. Because economic justice without gender justice is neither sustainable nor just.

As we go forward, let us keep this in mind: feminist foreign policy is not merely about summit-level diplomacy—it is just as much about who may move across a border with respect, who may access markets, who is shielded from violence, and who benefits from the dividends of economic integration. As long as the tomato seller on the border is heard as much as the minister on the summit, our trade policy will be an incomplete one.

AfCFTA is a historic chance. But it will only benefit Zimbabwe if it benefits Zimbabwean women. That requires us to re-imagine not only what we trade, but how we trade, and to whom. It is time we put the women who’ve long borne our economies on their backs front and centre. Let them now take the lead.

Leave Comments