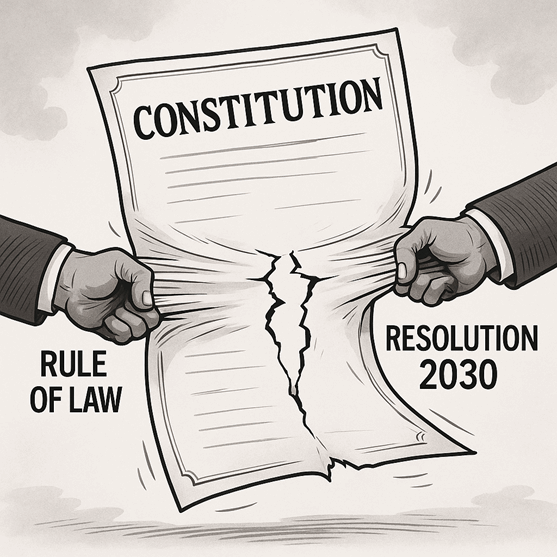

A heated legal storm has erupted over Resolution 2030 — the reported ZANU-PF plan to extend the presidential term from five to seven years.

What started as a party talking point has turned into a full-blown constitutional debate centred on Sections 91, 95 and 328 of Zimbabwe’s 2013 Constitution — and on one crucial question: can a sitting President legally benefit from such a change?

The Nyambirai Thesis: A Claimed Gap in the Law

Lawyer Tawanda Nyambirai sparked the row with an argument that Zimbabwe’s Constitution leaves a loophole.

He claims that nothing stops Parliament — without a referendum — from introducing a clause that extends the presidential term from five to seven years, and that the sitting President could legally benefit from it.

“There is nothing to stop ZANU-PF, through Parliament, and without referendum, from introducing a new constitutional provision providing for presidential term limits other than the five-year limit,” Nyambirai said.

Nyambirai argues that section 95 fixes a five-year term “except as otherwise provided,” suggesting Parliament could simply add a new term-length clause.

He also distinguishes between term length (how long one term lasts) and term limit (how many terms one can serve), saying only the latter triggers strict constitutional protection.

Pushback from the Bench: Coltart, Mupindu and Mpofu

Prominent lawyers quickly fired back.

David Coltart dismissed Nyambirai’s position as “utter nonsense,” saying section 95(2) must be read with the rest of the Constitution, which clearly sets each presidential term at five years.

“If its effect is to extend someone’s time in office, the incumbent cannot benefit,” Coltart added, citing section 328(7), which blocks any amendment that would give current office-holders extra time.

Tawanda Mupindu went further, calling the idea “completely false and unconstitutional.”

“Extending each term from five to seven years automatically extends the total time a person can occupy that office,” he argued, warning that this would breach Zimbabwe’s constitutional principles of rule of law and democracy.

Thabani Mpofu offered a more nuanced view: yes, the phrase “except as otherwise provided” could allow rare exceptions — for instance, election delays or re-runs — but not wholesale term extensions.

Related Stories

“That clause refers to legitimate extensions, not this contrived nonsense,” Mpofu said.

Constitutional Safeguards: What Section 328 Says

At the heart of the dispute lies section 328, which sets out the rules for changing the Constitution itself:

- Section 328(5): any amendment needs a two-thirds majority in both Houses of Parliament.

- Section 328(7): if a change extends term limits or benefits someone already in office, it does not apply to that person.

- Section 328(9): certain changes — including to section 328 itself — must go to a national referendum.

In plain terms, even if Parliament extended the presidential term to seven years, President Mnangagwa could not benefit unless section 328 were also amended — which would require a referendum.

Independent watchdog Veritas Zimbabwe reached the same conclusion: any such amendment “will not apply to President Mnangagwa” under section 328(7).

Caution from the Sidelines: Obey Shava’s Warning

Lawyer Obey Shava urged his peers not to get drawn into what he called a political trap.

“Don’t fall for ZANU-PF’s intelligence-gathering operation disguised as a debate. Exercise strategic silence and save your best arguments for court,” he said.

His warning reflects a wider fear that open legal sparring could help political strategists refine their plans or pre-empt counterarguments.

What It All Means: A Looming Constitutional Showdown

If ZANU-PF presses ahead with Resolution 2030, it faces a steep legal climb.

Changing term length alone is unlikely to survive constitutional scrutiny without navigating the safeguards of section 328.

And any move that lets the sitting President stay longer would, under the current Constitution, be invalid.

The only way around that would be to amend section 328 itself — a process that requires a referendum.

Whether Resolution 2030 is a real push or a political fishing expedition remains to be seen. But one thing is certain: the battle over Zimbabwe’s constitutional limits has only just begun.

Leave Comments